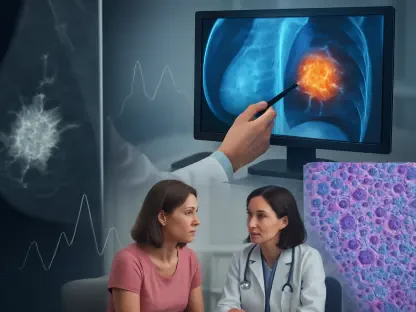

With over two decades of research in biopharma, Ivan Kairatov has witnessed the evolution of microbiome science from a niche interest into a central player in our understanding of health. As an expert in R&D and technological innovation, he has a unique perspective on the translational gap—the frustrating chasm between promising lab discoveries and effective patient therapies. In this interview, he explores why so many microbiome interventions fail to deliver on their initial hype. We’ll discuss the immense challenge of moving from simple association to proven causation in disease, the critical shift from identifying bacterial species to understanding their metabolic functions, and how personalized medicine, powered by AI, holds the key to unlocking the true therapeutic potential of our microbial partners.

Many studies link gut dysbiosis to chronic diseases, yet struggle to prove causation. What are the biggest scientific hurdles in moving from correlation to a causal link, and how does this “dysbiosis deluge” impact the design and funding of new clinical trials?

The primary hurdle is the staggering biological complexity of a human being compared to a laboratory animal. In the lab, we can control every variable—genetics, diet, environment. In the real world, a person’s microbiome is shaped by a lifetime of unique exposures, medications, and habits. This creates a “dysbiosis deluge,” a flood of studies showing statistical links but failing to prove that a specific microbe is the culprit rather than just a bystander. Proving causality requires incredibly complex and prohibitively expensive experiments. For clinical trials, this is a massive challenge. When you can’t present a rock-solid causal mechanism, it’s incredibly difficult to convince funders to invest millions into a large-scale human study. The overwhelming number of associative findings creates a sense of scientific noise, making it hard to identify the signals worth pursuing.

Promising results from standardized animal models frequently fail in diverse human populations. Beyond diet and genetics, what specific ecological factors, like microbial resilience, most complicate this transition? Please share a step-by-step example of how a therapy’s effects can be diluted in human trials.

One of the most powerful and often underestimated factors is the ecological resilience of the native human microbiome. Think of it as a deeply rooted, ancient forest. A therapy, like a probiotic, is like trying to introduce a new, non-native sapling. The existing ecosystem is highly adapted and competitive, and it will actively resist change. Here’s how a promising therapy can get diluted: First, in a sterile lab mouse, a single bacterial strain shows a remarkable ability to improve metabolic health. Second, this same strain is given to a human patient whose gut contains trillions of microbes that have co-evolved for decades. Third, the new therapeutic bacteria must immediately compete for limited space and nutrients against an established, highly efficient community. Finally, the host’s own diet and immune system, which are accustomed to the original microbiome, work to restore the previous balance. The initial, often modest, therapeutic effect quickly fades as the native community simply outcompetes and overwhelms the newcomers, returning the system to its baseline state.

Research often highlights functional redundancy, where different bacterial species can perform the same metabolic jobs. How should clinicians shift their focus from bacterial names to their functional pathways? What practical tools or metrics are needed to begin profiling microbial function in a standard clinical setting?

This is perhaps the most crucial shift in thinking our field needs to make. Focusing on bacterial names—the taxonomy—is like trying to understand a city’s economy by only reading a census of last names. What truly matters are the jobs people are doing. Functional redundancy means your gut might use a Bacteroides species to produce a vital short-chain fatty acid, while my gut uses a completely different Clostridium species to do the exact same job. The end result for our health is identical. Clinicians need to stop asking “Which bacteria are present?” and start asking “Which metabolic functions are active or deficient?” To make this practical, we need to develop standardized, accessible clinical tools that go beyond just sequencing. We need assays that can quickly and affordably measure the key metabolic outputs of the microbiome—the postbiotics and other bioactive compounds—in a way that’s as routine as a standard blood panel for cholesterol or glucose.

Interventions like Fecal Microbiota Transplants (FMT) can temporarily improve insulin sensitivity but often fail to produce lasting change. What key host or ecological factors typically override the transplant’s effects, and what would a more personalized, durable version of this therapy need to entail?

We’ve seen this play out in studies where FMT in men with metabolic syndrome improved insulin sensitivity for a few weeks, but it didn’t lead to weight loss or any durable metabolic change. The transplant is fighting an uphill battle against the host’s entire system. The host’s long-term diet, their immune system’s memory, and even the physical environment of their gut are all powerfully calibrated to the original microbiome. These forces act in concert to eventually reject or sideline the transplanted community. A truly durable therapy can’t just be a one-time transplant. It would need to be a holistic, personalized strategy. This would involve carefully matching the donor to the recipient based on functional profiles, and then critically, following the transplant with a sustained, personalized dietary regimen—using specific prebiotics and foods—designed to selectively feed and support the new microbial community, giving it the crucial advantage it needs to successfully establish itself for the long term.

Prebiotics are marketed as generic fiber supplements, but their success depends on a person’s existing microbiome. How can we better predict who will respond to a specific prebiotic, and what biomarkers are needed to effectively match individuals with the right dietary fiber intervention?

The way we currently approach prebiotics is fundamentally flawed. Promoting them as a one-size-fits-all solution is like selling gasoline to someone without knowing if they own a car. If a person’s microbiome lacks the specific bacteria equipped with the right enzymes to break down a particular fiber, that supplement will have little to no benefit. Prediction is the key. To get there, we need to move toward functional baseline profiling before any intervention. We need biomarkers that identify the presence and abundance of key metabolic pathways. A future diagnostic test wouldn’t just give you a list of bacteria; it would provide a functional readout. It could tell a patient, “Your microbiome has a high capacity to metabolize fructans but a very low capacity for galactooligosaccharides.” This allows us to classify individuals as likely “responders” or “non-responders,” enabling us to match the right person with the right fiber for a predictable and meaningful health benefit.

AI models show promise for predicting outcomes like blood sugar response by integrating microbiome and lifestyle data. What are the main hurdles—such as data validation or model transparency—preventing these AI tools from being used routinely by physicians today? Please describe the roadmap to get there.

The potential is enormous, but the hurdles are just as significant. The two biggest are validation and transparency. A physician simply cannot act on a recommendation from an AI “black box” without understanding its reasoning. These models also need to be rigorously validated across diverse populations to ensure they’re not just accurate for the specific group they were trained on. The roadmap to clinical integration is a careful, multi-step process. First, we must standardize how we collect multi-omics and lifestyle data to create larger, more reliable datasets. Second, the field must prioritize the development of “explainable AI,” models that can show their work and highlight the key features driving a prediction. Finally, and most importantly, these AI-driven recommendations must be tested in prospective, real-world clinical trials to prove they lead to better patient outcomes. Only after clearing these high bars for safety, efficacy, and trust can these powerful tools transition from the lab to the doctor’s office.

What is your forecast for microbiome therapies over the next decade? What specific breakthroughs in functional profiling or personalized medicine must occur for these treatments to become a mainstream clinical reality?

My forecast is one of cautious but profound optimism. The next decade will not deliver a single magic pill for the microbiome. Instead, we will see the rise of true precision medicine in this space. The era of generic, one-size-fits-all interventions is ending. The single most critical breakthrough we need is the development and widespread adoption of rapid, affordable, and clinically-validated functional profiling. We have to get to a point where a clinician can easily order a test that reveals what a patient’s microbiome is doing metabolically, not just which species are present. Once we can reliably identify a patient’s specific functional deficiencies, we can classify them as a likely responder to a targeted therapy. This will unlock the potential for highly effective, next-generation probiotics, precisely matched prebiotics, and engineered postbiotics that will finally transform two decades of fascinating research into durable, mainstream clinical reality.