A groundbreaking discovery has unveiled a class of small molecules that effectively teach the body to eliminate its own disease-causing components, a development that could rewrite the rules for treating some of the most stubborn medical conditions. An international team of scientists has engineered these molecules, known as “iDegs,” to accelerate the natural removal of specific proteins, offering a sophisticated new strategy in the ongoing battle against cancer and other complex ailments. This approach moves beyond simply blocking harmful proteins and instead marks them for complete destruction, neutralizing threats that have long been considered untouchable by conventional medicine.

The significance of this breakthrough lies in its potential to solve one of modern pharmacology’s most persistent challenges: the vast number of disease-related proteins that are “undruggable.” For a drug to work, it typically needs a well-defined pocket on a protein to bind to, like a key fitting into a lock. However, a majority of the proteins that drive human diseases lack such features. The development of iDegs presents a new paradigm in Targeted Protein Degradation (TPD), a field dedicated to overcoming this limitation. By leveraging the cell’s own internal disposal system in a novel way, this research opens the door to developing therapies for targets that have remained beyond the reach of traditional pharmaceuticals.

What if a Disease’s Master Switch Could Be Flipped, Then Broken Off Entirely

For decades, the primary strategy in drug development has been inhibition—designing molecules that block the function of a harmful protein. This is akin to jamming a key in a lock to prevent it from turning. While effective in many cases, this approach has limitations. The protein, though disabled, still exists within the cell and can sometimes perform other, unintended functions that contribute to disease. This has led researchers to pursue a more definitive solution: not just turning the switch off, but removing it from the circuit entirely.

This ambition is the driving force behind the field of Targeted Protein Degradation. TPD aims to co-opt the cell’s ubiquitin-proteasome system, a natural and highly efficient process for identifying and dismantling damaged or unnecessary proteins. It is the cell’s own quality control and recycling center. Early TPD drugs, known as PROTACs, work by acting as a molecular matchmaker, physically linking a target protein to a component of this disposal system. The new research, however, reveals a more subtle and potentially more powerful method that works with the cell’s existing logic rather than imposing a new one.

The Undruggable Dilemma Why Most Disease Causing Proteins Evade Treatment

The human proteome, the complete set of proteins expressed by our genes, is a landscape of immense complexity. While thousands of these proteins have been linked to various diseases, it is estimated that over 85% of them lack the distinct binding sites necessary for traditional drugs to latch onto. These “undruggable” proteins often function through complex interactions or lack deep, well-defined pockets, rendering them invisible to conventional inhibitors. This has created a significant bottleneck in treating a wide range of conditions, from aggressive cancers to neurodegenerative disorders, where the key culprits cannot be effectively targeted.

The development of TPD technologies offered a promising workaround. By focusing on degradation instead of inhibition, scientists could target proteins that were previously inaccessible. The first generation of these drugs builds an artificial bridge between the target protein and an E3 ligase, an enzyme that acts as a “tagger” for the cell’s disposal machinery. This strategy has shown significant promise but requires designing a complex molecule that can successfully bind to two different proteins simultaneously. This approach has proven challenging and is not universally applicable, leaving many critical disease-causing proteins still out of reach.

A Paradigm Shift Hijacking the Cell’s Natural Housekeeping

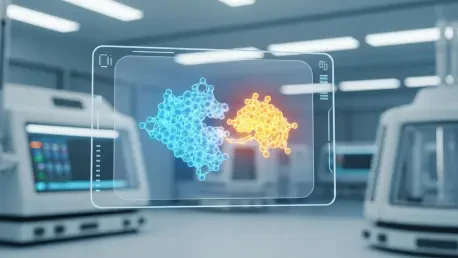

Recent findings introduce a more elegant strategy with the discovery of “iDegs,” a novel class of small molecules that enhance a natural process rather than creating an artificial one. These molecules do not act as a bridge. Instead, they bind to their target protein in a way that subtly changes its shape, effectively revealing a hidden “degrade me” signal. This altered conformation makes the protein a prime target for its native E3 ligase—the one the cell would naturally use to dispose of it—thereby amplifying an existing cellular pathway.

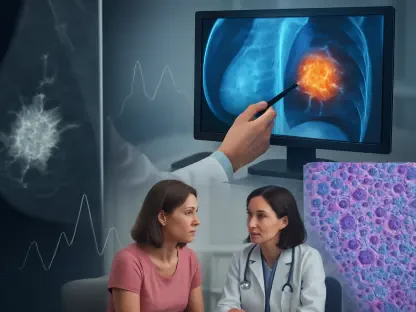

This principle was demonstrated in a compelling case study involving indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase 1, or IDO1, an enzyme that many tumors use as a personal bodyguard. IDO1 helps tumors evade the immune system by depleting tryptophan, an amino acid essential for immune cell function. Previous attempts to develop drugs that merely inhibited IDO1’s enzymatic activity failed in clinical trials. It became clear that the IDO1 protein also possessed other, non-enzymatic functions that continued to suppress immunity even when its primary function was blocked. Simply silencing the enzyme was not enough; the entire protein had to be eliminated.

The iDegs developed to target IDO1 deliver a powerful dual-action takedown. First, by binding to the enzyme, they effectively shut down its ability to metabolize tryptophan, delivering the inhibitory effect of previous drugs. But crucially, this binding event also triggers the complete destruction of the protein. This one-two punch of “inhibit and annihilate” ensures that all of IDO1’s immunosuppressive activities are neutralized. The strategic advantage is clear: total protein elimination removes the problem at its source, preventing the target from contributing to disease through any of its functions.

Unveiling the Molecular Blueprint How to Make a Protein Undesirable

Through detailed biochemical analysis and structural biology, researchers were able to map out the precise molecular choreography behind the iDegs’ effectiveness. The journey begins when the iDeg molecule, derived from a natural compound, binds to the IDO1 enzyme. This binding event physically dislodges an essential component of the enzyme known as a heme cofactor. Losing this cofactor is a destabilizing blow to the protein’s structural integrity.

The loss of the heme group forces the IDO1 protein to contort into a new, “degradation-sensitive” shape. This altered conformation is the critical step. In its normal state, IDO1 is relatively stable, but this new shape acts as a flag for the cell’s cleanup crew. It is this specific, drug-induced shape that is recognized by the protein’s natural E3 ligase partner, a molecule named KLHDC3.

Once KLHDC3 identifies the misshapen IDO1, it efficiently tags it with ubiquitin molecules, marking it for disposal. This tag is a signal for the proteasome, the cell’s molecular shredder, to grab the protein and dismantle it into its constituent amino acids. By making the protein undesirable to the cell in its natural state, the iDeg effectively accelerates a process that might otherwise happen slowly or not at all, ensuring the swift and complete removal of the tumor’s defensive shield.

A New Playbook for Drug Discovery The Future of Degrader Drugs

This discovery establishes a powerful new principle for future drug development: instead of forcing an interaction, researchers can learn to amplify a protein’s inherent weaknesses. The core concept is to identify small molecules that can push a target protein into a naturally unstable state, thereby hijacking its endogenous degradation pathway. This represents a fundamental shift in how scientists can approach the “undruggable” proteome.

This approach is particularly promising for a whole class of proteins that naturally cycle between stable and unstable conformations as part of their normal function. By designing drugs that trap these proteins in their unstable form, it may be possible to induce their degradation on command. This opens up a vast new hunting ground for drug developers, filled with targets that were previously considered impossible to hit with any degree of specificity or effectiveness.

The ability to manipulate a protein’s stability rather than just its active site provides a much more versatile and potentially more potent therapeutic tool. The insights gained from the IDO1 case study provided a blueprint for creating a next generation of degrader drugs. These therapies could offer new hope for challenging diseases by selectively removing the proteins that lie at their very foundation, marking a pivotal moment in the evolution of precision medicine. The work demonstrated a pathway toward a future where the list of “undruggable” targets could shrink dramatically, transforming the therapeutic landscape.