Today we sit down with Dr. Ivan Kairatov, a veteran biopharma expert whose work at the intersection of medicinal chemistry and computational biology is pushing the boundaries of treatment for central nervous system disorders. For decades, the neurokinin-1 receptor, or NK1R, was a tantalizing but ultimately frustrating target in the hunt for new antidepressants. After a series of high-profile clinical trial failures, the field largely moved on. Dr. Kairatov and his collaborators, however, saw an opportunity not to abandon the target, but to fundamentally rethink the chemistry used to engage it. We’ll be discussing how his team leveraged machine learning to resurrect this dormant target, the intricacies of their novel compound’s action in preclinical models, its unique molecular interactions, and what this breakthrough means for the future of treating inflammation-associated depression.

The neurokinin-1 receptor was once a promising but ultimately disappointing target for depression. What specific chemical features of early antagonists led to their failure, and how did your machine-learning approach help you design a molecular scaffold that successfully overcomes those previous limitations?

It’s a fascinating story of a target that was almost relegated to the history books. The early NK1R antagonists, like aprepitant, were heavily defined by a specific chemical feature: the 3,5-bis-trifluoromethylphenyl group, or TFMP. This moiety was, for a long time, considered essential for potent binding to the receptor. However, hindsight and further analysis suggest it may have been an Achilles’ heel. Molecules built around the TFMP group often had problematic pharmacokinetic properties or potential off-target effects that muddied the clinical waters. The results were inconsistent, and it became impossible to tell if the failures were due to the drugs themselves or the NK1R target. We hypothesized that the problem wasn’t the target, but our chemical key. This is where machine learning became transformative. Instead of incrementally modifying the flawed TFMP scaffold, we used our computational platform to screen millions of diverse molecules in silico. The goal was to find completely new structural starting points that lacked the TFMP group but could still potently inhibit NK1R. It wasn’t just about filtering; it was about identifying novel chemical architectures that could engage the receptor in a new way, allowing us to ask the original question again with a much cleaner tool.

Your research highlights compound #15, which reduced depressive-like behaviors and neuroinflammation in mouse models. Could you describe these preclinical models in more detail and explain how you measured these outcomes? Why was it crucial to demonstrate that the compound did not affect general locomotion?

To truly test the antidepressant potential of compound #15, we had to mimic the conditions of depression in animal models, which we approached from two angles: stress and inflammation. For the stress-induced model, mice are subjected to unpredictable, mild stressors over a period of time, which reliably induces behaviors analogous to human depression, such as anhedonia or a lack of interest in rewarding activities. For the inflammation model, we can induce a systemic inflammatory response that we know impacts the brain and behavior. In both cases, we measured depressive-like behaviors using established tests, like the forced swim test, where we observe how long an animal persists in trying to escape an unavoidable situation. A longer period of immobility is interpreted as a state of behavioral despair. We also measured neuroinflammation directly by analyzing brain tissue for markers of inflammatory cells and signaling molecules. Crucially, we also ran open-field tests to measure general locomotion. This is a critical control. A drug could reduce immobility in the forced swim test simply by being a stimulant, which isn’t an antidepressant effect. By showing that compound #15 didn’t increase general movement, we could be much more confident that its effects were genuinely related to mood and motivation, not just a non-specific change in activity levels.

The new compounds reportedly bind to the NK1 receptor through a “distinct interaction profile.” Can you walk us through what this means at the molecular level? How might this unique binding mechanism translate into improved antidepressant efficacy and a better side-effect profile in patients?

This is really the heart of our chemical innovation. When we say a “distinct interaction profile,” we mean that our new molecules are physically docking with the NK1 receptor in a different way than the older TFMP-containing drugs. Think of a lock and key. The old key fit, but maybe it jiggled, hit other parts of the lock, or didn’t turn the mechanism perfectly. Our new compound, #15, is like a key that was designed from scratch for a more precise fit. At the molecular level, this could mean it forms different hydrogen bonds or hydrophobic interactions with the amino acids in the receptor’s binding pocket. It might also induce a subtly different conformational change in the receptor upon binding. This is incredibly important because the specific shape the receptor takes dictates the downstream signals it sends inside the neuron. A more precise interaction could lead to a cleaner, more targeted signal, which would theoretically translate to higher efficacy. Furthermore, this unique binding mode means it’s less likely to interact with other, unintended receptors in the brain and body. This improved selectivity is the holy grail for medicinal chemists, as it’s the primary way we design out the unwanted side effects that plagued so many earlier psychiatric drugs.

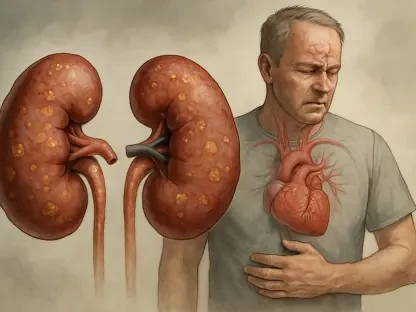

Inflammation is increasingly implicated in certain depression subtypes. How do these structurally novel NK1R antagonists specifically target neuroinflammation? What steps and potential biomarkers would be critical for designing a future clinical trial focused on patients with treatment-resistant or inflammation-associated depression?

The link is quite direct. The natural ligand for the NK1 receptor is a peptide called Substance P, which is not only a neurotransmitter involved in pain and mood but also a potent pro-inflammatory molecule. When Substance P binds to NK1R on immune cells in the brain, like microglia, it activates an inflammatory cascade. By developing a potent antagonist that blocks this receptor, we are essentially cutting a key communication line that drives neuroinflammation. Our compound #15 acts as a shield, preventing Substance P from delivering its inflammatory message. For a future clinical trial, this mechanism offers a clear strategy. We wouldn’t just recruit patients with a general depression diagnosis. Instead, we would use a biomarker-driven approach to enrich the study with patients most likely to respond. The critical first step would be to screen individuals for elevated inflammatory markers in their blood, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) or specific cytokines like Interleukin-6 (IL-6). By selecting patients with a clear “inflammatory signature,” we could test the hypothesis that dampening neuroinflammation via NK1R antagonism provides a significant antidepressant benefit, particularly for those who haven’t responded to traditional treatments.

This work suggests a powerful strategy of revisiting abandoned drug targets with modern computational tools. Beyond the NK1 receptor, what other previously failed targets in psychiatric drug discovery might be ripe for re-exploration, and what key lessons from this project could guide that process?

Absolutely, this is a blueprint for breathing new life into old ideas. The “pharmacological graveyard” is filled with promising targets that were abandoned not because the biology was wrong, but because the chemistry wasn’t right. I believe targets like the sigma-1 receptor or certain subtypes of phosphodiesterase (PDE) enzymes, which showed early promise but were derailed by compounds with poor selectivity or side-effect profiles, are prime candidates for this approach. The key lesson from our NK1R project is one of humility and perseverance: we must be willing to question foundational assumptions, like the necessity of a particular chemical scaffold. The second lesson is the power of our new tools. Machine learning and advanced structural biology allow us to explore chemical space with a breadth and speed that were unimaginable twenty years ago. We can now design molecules with surgical precision. The process for re-exploring these targets should be to first deeply analyze the historical failures, identify the specific chemical liabilities of the original drug candidates, and then deploy computational strategies to design entirely novel molecular series that sidestep those old pitfalls from the very beginning.

What is your forecast for the development of NK1R antagonists as a viable treatment for major depressive disorder?

I am cautiously optimistic, but I believe the future for NK1R antagonists is as a targeted, precision treatment rather than a broad, first-line therapy. This study provides a powerful proof-of-concept that the target is indeed viable, but the path to the clinic is still long. The next critical steps will involve rigorous safety testing and then, most importantly, clinical trials that are intelligently designed to enroll the right patient population—specifically, individuals with treatment-resistant depression that has a clear inflammatory component. If these trials can demonstrate a robust effect in that biomarker-selected group, I foresee NK1R antagonists carving out an essential niche in our therapeutic arsenal. It won’t be a magic bullet for all depression, but for the millions of patients whose condition is driven by underlying inflammation and who don’t respond to current drugs, it could represent a true breakthrough and a new ray of hope.