As a Biopharma expert at the forefront of tech and innovation, Ivan Kairatov is revolutionizing how we study the human brain. His work focuses on developing advanced, human-relevant models known as brain microphysiological systems to enhance the safety of chemical and drug testing. In our discussion, he delves into how these sophisticated 3D models are replacing outdated animal studies, offering deeper insights into neurotoxicity and disease. We explore the powerful combination of CRISPR gene editing and high-content imaging used to observe neural development in real time, the groundbreaking concept of “organic intelligence” to model cognitive functions like memory, and the path toward personalized, sex-specific neuroscience. Finally, he addresses the critical challenges of standardization and regulatory acceptance that must be overcome to fully realize the potential of these incredible systems.

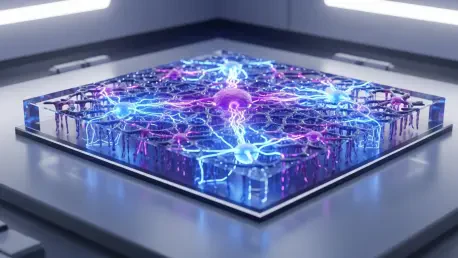

Brain microphysiological systems represent a major leap from traditional 2D cultures. Can you walk us through the key structural and functional features these 3D models capture, and how this complexity provides more physiologically relevant insights into human neurodevelopment?

Absolutely. We are essentially building miniature, functional pieces of the human brain in a dish. These aren’t just flat layers of cells like in traditional 2D cultures; our systems, whether they are organoids or organ-on-chip platforms, are complex three-dimensional structures derived from human stem cells. They self-organize to replicate key aspects of brain architecture, including the diverse mix of cell types and the formation of intricate neural networks. This complexity is what makes them so powerful. We can actually witness neurons firing and creating connections, a dynamic process that is impossible to see in a static 2D model. This allows us to observe neurodevelopment as it happens, giving us a far more accurate window into how the human brain forms and functions.

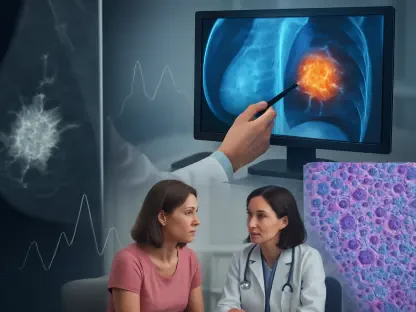

Given that a single animal neurotoxicity study can cost over a million dollars, how do bMPS offer a more efficient and human-relevant alternative? What specific limitations of animal models, particularly in capturing genetic or sex-specific responses, do they help overcome?

The shift away from animal models is driven by both ethical and scientific imperatives. The financial cost is staggering—a single developmental neurotoxicity study can easily exceed a million dollars and involve over a thousand rats—but the scientific cost is even greater. Animal models often fail to capture uniquely human biological processes, leading to misleading results. Our brain microphysiological systems are derived directly from human cells, which means they inherently reflect human biology. This allows us to explore nuances that are lost in animal studies, such as how a specific genetic variant might predispose someone to a neurological disorder or why males and females might respond differently to a drug. We can run tests at a much higher throughput, examining long-term, low-dose exposures that would be impractical and costly in animals, giving us a much clearer picture of real-world risks.

Your work combines CRISPR gene editing with high-content imaging. Could you describe the process of creating a fluorescent reporter line and what key developmental markers, such as synaptogenesis or apoptosis, you are able to track in real-time using this powerful approach?

This combination of technologies is truly transformative for our research. We use CRISPR/Cas9 as a molecular tool to precisely insert a gene for a fluorescent protein into the DNA of our stem cells. This protein is designed to light up only when a specific biological process occurs, like the birth of a new neuron or the formation of a synapse. Once we have this “reporter line,” we can grow it into a 3D brain model. Using high-content imaging systems, we can then watch these events unfold in real time under the microscope. We can quantitatively measure critical markers—seeing the flash of new cell proliferation, the dimming signal of apoptosis or cell death, and the intricate web of synaptogenesis as connections form. It’s a dynamic, visual readout of brain development that is both efficient and highly reproducible.

Research has shown that low-dose chemical exposure can impair neural network function without causing immediate cell death. Can you share an example of this and explain why detecting these subtle neurotoxic impacts is so critical for assessing the safety of everyday environmental chemicals?

This is one of the most crucial areas where our models excel. We conducted a study on domoic acid, a neurotoxin sometimes found in contaminated seafood. We exposed our brain models to chronic, very low doses—levels that didn’t kill the cells outright. From a simple viability test, you might conclude the chemical is safe. However, when we looked at the electrical activity of the neural networks, we saw a very different story. The networks’ ability to fire in a synchronized, plastic way was significantly impaired. Detecting these subtle, functional deficits is incredibly important because they may represent the earliest stages of neurodevelopmental damage from environmental chemicals we encounter daily. These are the kinds of impacts that could lead to learning disabilities or other neurological issues down the line, and they are completely invisible to traditional toxicology tests that only look for cell death.

You’ve introduced an “organic intelligence” concept for modeling cognitive functions in vitro. How do you combine brain organoids with microelectrode arrays and machine learning to train them, and how might this serve as an analog for learning and memory tests typically performed in animals?

The concept of “organic intelligence” pushes the boundaries of what we can model in a lab. We place our brain organoids onto high-density microelectrode arrays, which can both record the electrical activity of the neurons and deliver precise electrical stimuli. We then use machine learning algorithms to create a feedback loop. For example, we can present the organoid with a specific pattern of electrical pulses and “reward” it with a different stimulus when its network activity begins to match a desired pattern. In essence, we are training the living neural network to respond to its environment. This is a foundational step toward creating an in vitro analog for cognitive functions. Instead of watching a rat navigate a maze to test its memory, we could one day assess a chemical’s impact on a brain organoid’s ability to learn and remember a specific electrical pattern.

Since these models can be derived from donor-specific cells, how are you using them to investigate sex-based biological differences or genetic variants in neurological conditions? Can you provide an example of how integrating immune cells helps explore neuroinflammatory mechanisms in certain disorders?

The personalized nature of these models is one of their greatest strengths. We can take skin or blood cells from any individual, reprogram them into stem cells, and then grow a brain model that is genetically their own. This opens the door to studying why certain neurological conditions manifest differently based on sex or specific genetic mutations. For instance, we can create models from individuals with a genetic predisposition to autism and integrate immune cells like microglia into them. By doing this, we can directly observe the neuroinflammatory processes that are thought to play a role in the disorder, watching how the immune cells interact with neurons in a patient-specific context. This provides a powerful platform for understanding disease mechanisms and testing targeted therapies.

For bMPS to gain widespread regulatory acceptance, standardization is a key hurdle. Based on your experience, what are the most critical challenges—from iPSC variability to adapting assay endpoints—and what practical steps can labs take to improve reproducibility and build confidence in these models?

Standardization is absolutely the biggest mountain we need to climb for regulatory acceptance. The challenges are multifaceted. Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) lines themselves can have inherent variability, and the protocols to differentiate them into brain models are long and require significant technical skill, leading to differences between labs. Furthermore, many of the standard tests, or endpoints, used in toxicology were designed for simple 2D cell cultures and just don’t work in a complex 3D environment. To move forward, we need to establish harmonized protocols and quality control metrics. Labs need to invest in robust characterization of their cell lines and models. It’s about building a foundation of reproducibility and reliability, demonstrating that the data we generate is consistent and trustworthy, which is the only way we’ll build the confidence needed for regulatory bodies to adopt these powerful new tools.

What is your forecast for brain microphysiological systems?

I am incredibly optimistic. I foresee these systems becoming a cornerstone of both preclinical drug development and chemical safety assessment within the next decade. The momentum is already building, with regulatory bodies like the OECD beginning to adopt in vitro methods. As the technology matures and standardization improves, we will move beyond simply identifying toxicity to predicting complex, human-specific outcomes, from cognitive impairment to individual drug responses. Ultimately, these models will not only drastically reduce our reliance on animal testing but will also usher in an era of precision toxicology and personalized neurology, making our medicines and our world safer for the human brain.