Congenital heart disease stands as the most common and resource-intensive birth defect in the United States, thrusting thousands of families each year into a world of high-stakes surgeries and lifelong medical care. While the clinical focus has traditionally been on the patient’s condition and the surgeon’s skill, a groundbreaking research initiative is asking a more unsettling question: What if the greatest risks to these vulnerable children lie not just in their hearts, but in the fragmented and unequal healthcare systems they are forced to navigate? A major $8.5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health is now funding a large-scale investigation to uncover how systemic factors determine which children thrive and which are left behind. The project, led by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, aims to move beyond individual patient risk factors to scrutinize the very structures and processes of care delivery. By leveraging massive datasets and an interdisciplinary approach, researchers hope to provide data-driven insights that can inform policy, reduce health disparities, and ultimately reshape the future for every child born with this challenging condition.

Uncovering a Deeper Problem

The Scale of the Challenge

Affecting approximately one in every 100 newborns, congenital heart disease presents an immediate and overwhelming challenge for families and the healthcare system alike. The condition’s severity often necessitates major open-heart surgeries within the first few years of life, a period fraught with risk and uncertainty. These complex procedures carry significant dangers, with national data indicating that over 10 percent of infants undergoing such interventions do not survive. For those who do, the journey is far from over. Survivors frequently live with persistent health issues that require continuous medical management, follow-up procedures, and specialized care throughout their lives. This long-term reality transforms a single birth defect into a lifelong condition, underscoring the critical need for a healthcare system that can provide consistent, high-quality support from infancy through adulthood. The initial surgical success is merely the first step in a marathon of care that tests the resilience of patients, families, and providers.

The sheer volume of care required places an immense burden on both families and public resources, illustrating the extensive impact of the disease beyond the operating room. A foundational study revealed a stark picture of this demand: children on Medicaid, on average, spent over 90 days engaged with the healthcare system—in hospitals and doctors’ offices—within the first five years following their initial cardiac surgery. This statistic not only highlights the profound disruption to a child’s early development and family life but also points to the significant economic strain on the healthcare infrastructure. Furthermore, the research uncovered wide variations in this healthcare utilization among different patient groups, even those who were clinically similar. This variability suggests that factors other than the child’s medical condition are at play, raising critical questions about the efficiency, equity, and consistency of the care being delivered across different providers and health networks, signaling a problem that is systemic in nature rather than purely clinical.

Alarming Gaps in Survival

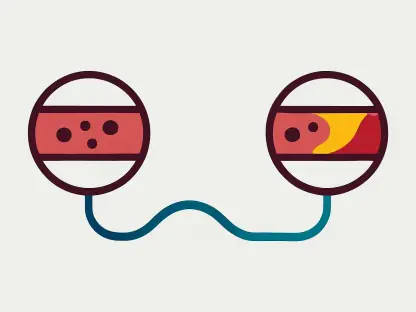

Beyond the universal struggles faced by families navigating congenital heart disease, a more disturbing and persistent pattern has emerged from the datsignificant and poorly understood racial and ethnic disparities in health outcomes. Compelling research has revealed that Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black children experience mortality rates that are 15 to 20 percent higher than those of their non-Hispanic white peers. This alarming survival gap is not a minor statistical variation but a profound inequity that points to deep-seated issues within the healthcare landscape. The consistency of this finding across multiple studies has elevated the issue from a secondary concern to a primary focus of investigation. Understanding the root causes of these disparities is no longer just an academic exercise but a moral and clinical imperative. The fact that a child’s chances of survival can be so closely tied to their racial or ethnic background challenges the very foundation of equitable medical care and demands a more critical examination of the systems in place.

What makes these disparities particularly troubling is that they persist even after researchers control for a wide range of variables. The survival gap remains statistically significant after adjusting for clinical risk factors, family income levels, neighborhood socioeconomic status, and even the specific surgical center where the procedure was performed. This crucial detail suggests that the problem cannot be attributed solely to the severity of a child’s condition, the financial resources of their family, or the quality of a single hospital. Instead, it points directly toward systemic failures woven into the fabric of healthcare delivery. These failures may involve biases in treatment, difficulties in navigating complex care networks, communication barriers, or other subtle yet powerful factors that disproportionately affect minority populations. By ruling out many of the most common explanations, the data forces a difficult conclusion: the system itself, in its structure and function, may be contributing to these tragic and preventable losses.

Shifting the Focus From Patient to System

Pioneering Research Reveals Systemic Flaws

The foundation for this new, large-scale investigation was meticulously laid by an earlier project, the Congenital Heart Surgery Collaborative for Longitudinal Outcomes and Utilization of Resources (CHS-COLOUR). This pioneering initiative, centered in New York, developed the first-ever statewide data network by uniting information from nearly all of the state’s congenital heart centers with records from the New York State Department of Health. Its truly innovative approach involved linking detailed clinical registry data with comprehensive insurance claims data. This methodology allowed researchers to move beyond the isolated context of a single surgery or hospital stay and construct a holistic view of each child’s real-world healthcare journey over several years. By analyzing how, when, and where children received care, the project began to unravel the complex interplay between clinical needs and the healthcare structures that were supposed to meet them, setting a new standard for outcomes research in pediatric cardiology.

This initial phase of research yielded crucial and transformative insights that shifted the conversation from patient-centric factors to systemic ones. The most significant discovery was that differences among the healthcare providers and networks treating these children could explain up to 20 percent of the observed variations in their health outcomes. This finding was a watershed moment, providing concrete evidence that the system of care is a powerful determinant of a child’s long-term survival and well-being. It demonstrated that two children with identical clinical profiles could have vastly different health trajectories based solely on the specific providers they interacted with over time. This conclusion directly challenged the traditional focus on individual patient risk and surgical technique, confirming that the fragmented nature of healthcare delivery and the specific pathways a family navigates are not just incidental details but are, in fact, critical factors that can mean the difference between thriving and facing persistent health crises.

Building a National Blueprint for Change

Fueled by the new $8.5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health, the research is undergoing a dramatic expansion, transforming from a single-state model into a national powerhouse for pediatric health research. The collaborative will now encompass all 25 congenital heart surgical centers across four geographically and demographically diverse states: New York, Massachusetts, Colorado, and Texas. This ambitious scale-up creates what is intended to be the most comprehensive and robust national resource to date for investigating the systemic drivers of health outcomes in children with CHD. By incorporating a much larger and more varied patient population, the project will be able to analyze patterns and disparities with greater statistical power and generalizability. This expanded dataset will enable researchers to identify best practices, pinpoint systemic weaknesses, and develop a national blueprint for change that can be adapted to improve care across the country.

A cornerstone of the project’s strength lies in its deeply interdisciplinary nature, which recognizes that the challenges of healthcare delivery cannot be solved from a single vantage point. The research team brings together a diverse group of 14 co-investigators, whose expertise spans a wide range of fields. This collaborative includes congenital heart surgeons, fetal and pediatric cardiologists, pediatricians, public health experts, health economists, biostatisticians, and even medical anthropologists. This integrated approach is essential for tackling the multifaceted questions at the heart of the investigation. While clinicians can provide insight into medical decision-making, health economists can analyze the financial structures that shape care, and social scientists can uncover the cultural and navigational barriers families face. By combining these perspectives, the team can dissect the complex functions of the healthcare system from every angle, leading to more holistic and effective solutions.

Mapping the Patient Journey for Better Outcomes

With its expanded scope and interdisciplinary team, the project had shifted its focus to develop a “deeper knowledge” of the entire patient and family journey through the healthcare maze. The research was designed to move beyond simply identifying that provider networks matter and instead investigated the critical “how” and “why” behind care navigation. Investigators planned to meticulously map the pathways families took, examining how they navigated complex insurance systems, made crucial decisions about prenatal care and birth centers, and selected the interconnected network of specialists—from pediatricians to cardiologists to surgeons—they would rely on throughout their child’s life. The goal was to understand the decision points, barriers, and facilitators that shaped these journeys. This granular level of analysis was intended to reveal the subtle but profound ways in which a family’s ability to access and coordinate care could ultimately influence their child’s long-term health trajectory across their entire life course.

Ultimately, the overarching objective of this monumental research endeavor was to translate data-driven insights into tangible, systemic change. The project was not conceived as a purely academic exercise but as a pragmatic tool to inform policy and fundamentally restructure care delivery for one of the nation’s most vulnerable pediatric populations. The findings were intended to equip providers, hospital administrators, and policymakers with the evidence needed to design more integrated, equitable, and effective systems of care. By identifying the specific systemic fractures that contributed to poor outcomes and health disparities, the collaborative sought to build a foundation for a future where every child with congenital heart disease had the best possible chance at a long and healthy life, regardless of their background or where they happened to live. This commitment to data-driven science represented a transformative potential to move beyond treating the disease and begin healing the system.