As modern life pulls us further from our natural rhythms, the consequences for our health are becoming clearer. I’m thrilled to sit down with Ivan Kairatov, a renowned biopharma expert with extensive experience in research and development, particularly in the intersection of technology and health innovation. With a deep understanding of how biological processes like circadian rhythms influence our well-being, Ivan is the perfect person to help us unpack the latest insights on how disruptions to our internal clock can impact cardiovascular and metabolic health. Today, we’ll explore the science behind our body’s 24-hour cycles, the ways our daily habits can throw them off balance, and practical steps to protect our heart health.

Can you walk us through what circadian rhythms are and why they’re so crucial for our health?

Absolutely. Circadian rhythms are the body’s internal 24-hour cycles that regulate a wide range of biological processes, from when we sleep and wake to how our hormones, digestion, and even body temperature function. They’re driven by a central clock in the brain, specifically in the hypothalamus, which syncs with environmental cues like light. These rhythms are vital because they ensure that our physiological processes happen at the right time—think of heart rate and blood pressure dipping at night for rest or metabolism ramping up during the day for energy. When these cycles are in harmony, they support overall health, but disruptions can throw everything out of whack, increasing risks for issues like heart disease.

How do our modern lifestyles interfere with these natural rhythms?

Modern life is almost designed to disrupt circadian rhythms. Irregular sleep schedules—staying up late or forcing early wake-ups—can misalign our internal clock with our daily behaviors. Beyond that, habits like excessive screen time, especially at night, expose us to artificial blue light that tricks our brain into thinking it’s daytime, delaying sleep. Shift work is another big factor, as it forces people to be active during their biological night. Even small inconsistencies, like changing sleep times on weekends, can create a kind of “social jet lag” that stresses the body over time.

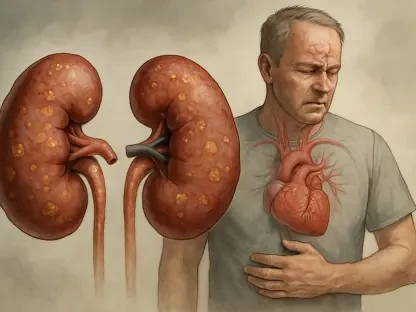

What’s the connection between these disruptions and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease?

The link is quite direct. When circadian rhythms are disrupted, it impacts key cardiovascular functions like heart rate and blood pressure, which normally follow a daily pattern of highs and lows. Chronic misalignment can lead to sustained high blood pressure or inflammation, both of which are major risk factors for heart disease. Additionally, disruptions can impair how the body handles stress hormones like cortisol, further straining the cardiovascular system. Over time, this can contribute to conditions like atherosclerosis or even increase the likelihood of heart attacks.

There’s also evidence linking circadian disruptions to obesity and Type 2 diabetes. How does this happen?

It comes down to how circadian rhythms regulate metabolism. When sleep or meal timing is inconsistent, it can mess with how our body processes energy. For instance, late-night eating or skipping breakfast can misalign the clocks in organs like the liver and pancreas, leading to inefficient glucose regulation and increased fat storage—hence, weight gain. This also raises blood sugar levels over time, heightening the risk of Type 2 diabetes. Essentially, our metabolic health thrives on consistency, and disruptions throw that balance off.

Why is the timing of sleep just as important as the amount of sleep we get?

Sleep duration matters, but timing is equally critical because it determines how well our internal clock aligns with our environment. If you sleep enough hours but at inconsistent times, your body struggles to maintain its natural rhythm. This can lead to metabolic and hormonal imbalances, as the body isn’t primed for rest or activity when it should be. Irregular timing, like shifting schedules between weekdays and weekends, creates that social jet lag I mentioned, which has been tied to higher risks of obesity and poor blood sugar control. Consistency in when you sleep helps keep everything in sync.

How does exposure to light play a role in maintaining or disrupting circadian health?

Light is the primary cue for our central clock. Morning sunlight helps reset and reinforce our natural rhythm, signaling to the body that it’s time to be alert and active. It boosts melatonin suppression during the day, which is a good thing for wakefulness. On the flip side, artificial light at night—especially blue light from phones or laptops—can suppress melatonin production when we need it most for sleep. Even dim light at night has been linked to cardiovascular risks because it disrupts the body’s ability to wind down and repair during rest.

Let’s talk about meal timing. How does when we eat affect our metabolic health?

Meal timing is incredibly important because our digestive and metabolic systems are wired to process food at certain times of day. Eating earlier, like having breakfast before 8 a.m., aligns with when our metabolism is most active, leading to better blood sugar control and lower diabetes risk. Late-night eating, however, works against this rhythm, often causing spikes or dips in glucose levels and promoting weight gain since the body isn’t as efficient at burning energy during rest. Irregular meal schedules can similarly confuse the peripheral clocks in organs like the liver, contributing to metabolic stress.

What about physical activity? Is there an ideal time to exercise for supporting circadian rhythms?

Exercise is a powerful secondary cue for circadian alignment, though the optimal time can vary. Morning or afternoon workouts tend to advance the body clock, helping you feel alert earlier and sleep better at night. They can also improve blood pressure and glucose control when timed right. Evening exercise, however, might delay the clock, making it harder to fall asleep for some people. That said, the best time often depends on individual chronotypes—whether someone’s a morning person or night owl—so personalizing activity timing can maximize its benefits for circadian and overall health.

Looking ahead, what’s your forecast for how research on circadian rhythms might shape health strategies in the coming years?

I’m optimistic that we’re on the cusp of a major shift. As technology advances, tools like wearables and AI will likely make it easier to track individual circadian patterns in real-world settings, not just controlled labs. This could lead to highly personalized health strategies—think tailored sleep, meal, and exercise schedules based on someone’s unique internal clock. I also expect more research to solidify the causal links between circadian disruptions and specific diseases, which could push circadian health into mainstream medical practice. Ultimately, we might see a future where aligning with our natural rhythms becomes a core pillar of preventive care for heart and metabolic health.