The quest to measure the true pace of human aging has moved from the realm of speculation into the molecular precision of the laboratory, powered by a technology that reads the subtle chemical tags accumulating on our DNA over a lifetime. The technology of epigenetic aging clocks represents a significant advancement in molecular biology, gerontology, and forensic science. This review will explore the evolution of these biological clocks, their underlying mechanisms, key performance metrics, and the impact they have on various applications. The purpose of this review is to provide a thorough understanding of the technology, its current capabilities, and its potential for future development.

The Foundation of Epigenetic Aging

The core principle behind this technology is that aging is more than the simple passage of time; it is a complex biological process marked by progressive, predictable changes at the molecular level. Epigenetics, the study of heritable changes in gene expression that do not involve alterations to the underlying DNA sequence, provides the framework for understanding these changes. These epigenetic modifications act as a layer of information on top of the genetic code, influencing which genes are turned on or off in different cells at different times.

This regulatory layer is highly dynamic and can be influenced by a host of factors, including diet, lifestyle, and environmental exposures. This dynamic nature is what makes the epigenome a powerful record of an individual’s life history and biological state. Consequently, it offers a way to distinguish between chronological age—the number of years a person has been alive—and biological age, which reflects the functional state of their cells and tissues. This distinction is central to modern aging research and the diagnostic potential of epigenetic clocks.

Core Mechanisms and Clock Construction

DNA Methylation as a Primary Aging Biomarker

The fundamental biological feature powering epigenetic clocks is DNA methylation. This process involves the addition of a methyl group to a DNA molecule, typically at specific locations known as CpG sites, which can alter the activity of a DNA segment without changing its sequence. Decades of research have revealed that patterns of DNA methylation across the genome change in a systematic and predictable manner as we age. Certain CpG sites tend to gain methylation over time, while others tend to lose it, creating a unique “methylation signature” for different age groups.

These age-associated methylation patterns are not random; they often occur in or near genes crucial for cellular function, development, and disease. For example, recent findings in skeletal muscle identified 20 distinct CpG sites whose methylation levels strongly correlate with age. These sites are located within genes integral to muscle function, metabolic regulation, and cellular stress responses. This direct link between an epigenetic mark and the regulation of key biological pathways provides a molecular basis for how these changes may contribute to the functional decline observed in aging.

Development of Predictive Machine Learning Models

The construction of an epigenetic clock is a sophisticated marriage of molecular biology and data science. The process begins by collecting biological samples—such as blood or tissue—from a large cohort of individuals with known chronological ages. The DNA from these samples is analyzed to measure methylation levels at hundreds of thousands of CpG sites across the genome. This vast dataset, pairing methylation patterns with chronological ages, becomes the training material for powerful machine learning algorithms.

These algorithms sift through the data to identify the specific CpG sites that are most predictive of age. By learning the complex relationships between methylation levels at these key sites and the donor’s age, the model builds a predictive algorithm. Once trained and validated on independent datasets, this algorithm can estimate an individual’s age from their DNA methylation data with remarkable accuracy. Advanced models developed for specific tissues, using methods like Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), now demonstrate a mean absolute error of just 3.8 to 5.5 years, establishing them as highly reliable predictive tools.

Recent Developments and Key Findings

One of the most critical trends shaping the trajectory of this technology is the move toward tissue-specific clocks. Early epigenetic clocks were often built using data from easily accessible tissues like blood and were assumed to be universally applicable. However, research now conclusively shows that epigenetic aging patterns are highly dependent on the tissue of origin. A clock developed using skeletal muscle, for instance, significantly outperforms generalized clocks when tested on muscle samples but loses its accuracy dramatically when applied to other tissues, such as cardiac or uterine muscle. This finding underscores that for molecular age estimation to be precise, it must be tailored to the specific tissue being analyzed.

Parallel to this, the influence of population genetics on clock accuracy is becoming increasingly apparent. A significant portion of the foundational research in this field was conducted using cohorts of European descent, raising questions about the universal applicability of the resulting clocks. More recent studies focusing on other populations, such as East Asians, have been crucial in addressing this gap. By developing clocks based on diverse cohorts, researchers are building a more comprehensive picture of epigenetic aging, revealing both universal markers and population-specific variations that must be accounted for to ensure equitable and accurate application of the technology worldwide.

Major Applications and Use Cases

Advancements in Forensic Science

In forensic science, epigenetic clocks provide a powerful tool for estimating the age of unknown individuals from biological remains. This capability is invaluable in criminal investigations, disaster victim identification, and anthropological studies where other evidence of age may be absent. A key advantage is the technology’s robustness; it can yield reliable age estimates even from DNA that is partially degraded, a common challenge forensic scientists face with aged or environmentally exposed samples.

The development of tissue-specific clocks further enhances their forensic utility. By creating models tailored for tissues commonly found at crime scenes, such as skeletal muscle, investigators can achieve a higher degree of accuracy than with generalized clocks. As these methods become more refined and cost-effective, they are poised to become a standard part of the forensic toolkit, offering objective, data-driven insights that can help narrow down the identity of unknown persons and provide crucial leads for investigators.

Implications for Gerontology and Clinical Medicine

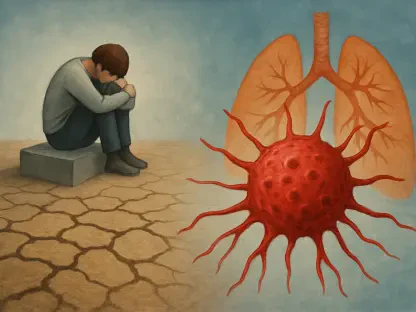

Beyond age prediction, these clocks are transforming our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of aging. In gerontology and clinical medicine, they serve as a dynamic biomarker of biological age, allowing researchers to measure “age acceleration”—the divergence between an individual’s biological and chronological age. This metric has been linked to lifestyle factors, chronic diseases, and overall mortality risk, making it a powerful endpoint for studies on health and longevity.

Furthermore, by identifying the specific genes affected by age-related methylation changes, this research provides direct targets for therapeutic interventions. For example, the discovery of methylation shifts in genes associated with sarcopenia—the progressive loss of muscle mass and strength—paves the way for developing treatments aimed at slowing or reversing this debilitating condition. This moves the field beyond simply measuring age toward actively managing the aging process at a molecular level.

Current Challenges and Limitations

Despite its rapid progress, the technology faces several significant challenges. The most prominent is the need for greater specificity. As demonstrated by recent research, a clock’s accuracy is heavily dependent on the tissue and population it was trained on. This means that a universal, one-size-fits-all clock remains elusive. Developing and validating a comprehensive library of clocks for various tissues, populations, and even different anatomical locations within the same tissue type is a major undertaking that is necessary for broad and reliable application.

Another conceptual hurdle is the interpretation of what epigenetic clocks truly measure. While they are trained to predict chronological age, their real value lies in quantifying biological age. However, biological age is not a single, universally defined concept; it is a complex mosaic of cellular and physiological states. Standardizing the definition and validation of biological age is essential for its use in clinical settings, where decisions about health interventions could be based on these measurements. Technical and logistical hurdles, including the cost and standardization of methylation analysis platforms, also remain barriers to widespread adoption.

The Future of Epigenetic Timekeeping

Looking ahead, the field is moving toward several exciting frontiers. A primary goal is the development of robust pan-tissue clocks that can accurately predict age from any biological sample, which would greatly simplify their practical application in both clinical and forensic contexts. Such a tool would require immense datasets and sophisticated algorithms capable of distinguishing tissue-specific noise from the universal aging signal.

The next evolution of this technology will likely shift from providing a static snapshot of age to measuring the rate of aging in real time. A clock that can quantify how quickly an individual’s biological age is changing could offer immediate feedback on the effectiveness of lifestyle changes or therapeutic interventions. In the long term, this capability could revolutionize personalized medicine, enabling healthcare providers to tailor wellness plans based on an individual’s unique molecular aging profile. The ultimate vision is one where epigenetic clocks not only predict age but also guide interventions designed to slow or even reverse age-related decline, fundamentally altering our approach to health and longevity.

Concluding Summary

Epigenetic aging clocks stand as a robust and highly accurate biomarker of age, representing a paradigm shift in how aging is measured and understood. The technology’s ability to translate complex molecular patterns into a single, interpretable metric has unlocked new possibilities across diverse scientific fields, from identifying unknown individuals in forensic cases to dissecting the fundamental biology of age-related diseases.

While challenges related to tissue specificity, population diversity, and clinical interpretation remain, the pace of innovation is rapid. The ongoing refinement of these clocks, coupled with a deeper understanding of the epigenetic mechanisms they measure, holds transformative potential. This technology is not merely a new way to tell time; it provides a powerful lens through which we can view the aging process itself, paving the way for future advancements that could profoundly impact human health, medicine, and our relationship with aging.