The quiet aftermath of a traumatic event often conjures images of panicked awakenings and a constant state of high alert, yet for the vast majority of survivors, the most debilitating struggle is a silent, internal battle waged not against terror but against a crushing weight of sorrow and self-blame. This profound disconnect between the public perception of post-traumatic stress disorder and the lived reality of most who suffer from it is now at the center of a scientific reckoning, one that promises to redefine the very nature of trauma recovery. For decades, the therapeutic and diagnostic framework for PTSD has been built almost exclusively around the concept of a fear-learning disorder. However, groundbreaking research now illuminates a different, more pervasive landscape of suffering, compelling a critical re-evaluation of how trauma is understood, diagnosed, and, most importantly, treated.

This shift in perspective is not merely an academic distinction; it carries urgent, real-world consequences for millions. The prevailing focus on fear has shaped treatment protocols, research funding, and public awareness, leaving many individuals feeling misunderstood and inadequately supported. When therapies designed to extinguish fear responses fail to alleviate the profound sadness or debilitating guilt that defines a person’s daily existence, it can lead to frustration and a sense of hopelessness. The emerging evidence suggests that for nearly seven in ten trauma survivors, the core of their distress lies in this domain of emotional pain. Recognizing this reality is the crucial first step toward developing more personalized, effective, and compassionate care that addresses the true source of an individual’s anguish, moving beyond a one-size-fits-all model toward a future where treatment aligns with the patient’s subjective emotional world.

When the Aftershock Is Not Fear a New View of Traumas Toll

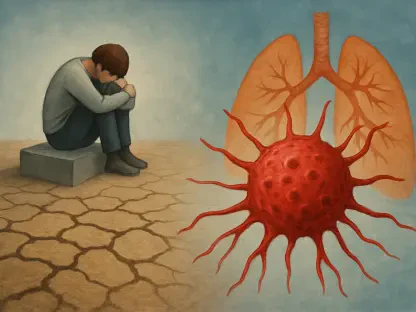

For a significant majority of individuals who have experienced trauma, the most persistent and impairing aftershock is not the reliving of terror but the navigation of a complex emotional terrain defined by guilt, shame, and profound sadness. A pivotal and unexpected statistic emerging from recent studies reveals a stark reality: for nearly 7 in 10 trauma survivors, this cluster of emotional pain symptoms is the primary driver of their daily struggle. This finding fundamentally challenges the conventional wisdom that has long positioned fear, hypervigilance, and intrusive memories as the central pillars of the post-traumatic experience. Instead, it suggests that the most common manifestation of trauma’s toll is a deeply internalized sense of brokenness.

This emotional pain often manifests as a pervasive feeling of worthlessness or a haunting sense of responsibility for the traumatic event, even when such beliefs are logically unfounded. Survivors may grapple with intense shame about their reactions during or after the event, or they may experience anhedonia—a near-total loss of joy or interest in activities they once cherished. This form of suffering erodes one’s sense of self and connection to others in a way that is distinct from fear-based anxiety. While fear keeps a person on guard against external threats, emotional pain turns the suffering inward, creating a state of chronic, quiet despair that can be far more corrosive to long-term mental health and daily functioning.

Beyond the Fear Learning Framework Why This Conversation Matters

The long-standing diagnostic model for PTSD has been deeply rooted in the principles of fear conditioning, viewing the disorder as a malfunction in the brain’s ability to process and extinguish a learned fear response. This framework, developed over decades of research, has been invaluable in explaining symptoms like hyperarousal and flashbacks. However, its dominance has inadvertently created a blind spot, overshadowing the equally debilitating, and evidently more common, symptoms of emotional pain. Challenging this decades-old model is not about discarding it entirely but about expanding it to reflect the full spectrum of post-traumatic suffering. By moving past the view of PTSD as a condition solely rooted in fear and anxiety, the clinical and scientific communities can begin to address the multifaceted nature of trauma’s impact.

This re-evaluation is driven by an urgent need for a broader therapeutic perspective. The limitations of current treatments become apparent when considering the significant number of individuals who do not fully respond to fear-focused interventions like exposure therapy. While these methods are effective for many, they may fail to target the core wounds of those whose primary struggle is with guilt, shame, or a shattered worldview. The necessity of re-evaluating therapeutic pathways is therefore paramount. Acknowledging that a majority of sufferers are contending with emotional pain opens the door to developing and prioritizing different types of interventions—therapies designed to rebuild a sense of self-worth, process moral injury, and reconnect with a sense of meaning and joy. This shift is essential for moving toward a more personalized and effective standard of care.

Unpacking Two Distinct Profiles of Post-Traumatic Stress

Within the broader diagnosis of PTSD, research has now clearly delineated two distinct clinical profiles, each with its own characteristic set of symptoms and experiences. The first is the classic, fear-based profile that has long defined the disorder in both clinical settings and the public imagination. This experience is characterized by the traditionally recognized symptoms that stem from an overactive threat-detection system. Individuals in this cluster are often plagued by vivid flashbacks, intrusive and distressing memories of the event, and a state of chronic hyper-arousal, feeling constantly on edge and easily startled. Their world becomes organized around the avoidance of triggers that might reactivate the terror of the original trauma, leading to a constricted and fear-driven existence.

In stark contrast is the overlooked emotional pain experience, which the latest data suggests is the more dominant reality for trauma survivors. This profile is not primarily defined by a fear of recurrence but by debilitating internal states. Its hallmarks are a pervasive sense of guilt over actions taken or not taken, profound shame that can feel isolating and toxic, and a deep, persistent sadness that often resembles major depression. A key symptom is anhedonia, the inability to derive pleasure from life, which leaves individuals feeling emotionally numb and disconnected from others. The most compelling finding is that these emotional pain symptoms were reported to be more functionally impairing for 68% of individuals studied, significantly interfering with their ability to work, maintain relationships, and engage with their lives in a meaningful way.

The Scientific Evidence Behind the Discovery

This new understanding of trauma is not based on anecdotal reports but on rigorous scientific investigation that separates subjective experience into distinct biological and psychological phenomena. Dr. Ziv Ben-Zion, a lead researcher in this area, describes the source of this emotional pain as a “moral and existential wound.” Trauma, in this context, does more than trigger a fear response; it can shatter a person’s core beliefs about their own goodness, the reliability of others, or the fundamental fairness of the world. For some, the event acts as a devastating confirmation of pre-existing feelings of worthlessness, deepening a lifelong struggle with shame and self-blame. This internalized wound, tied to identity and meaning, becomes the primary engine of ongoing distress.

Further insight comes from Dr. Ilan Harpaz-Rotem, who hypothesizes that these two profiles are driven by distinct neurobiological mechanisms. He notes that decades of research have focused intensely on the brain’s fear circuitry, leading to a tale of two biological systems where one has been extensively mapped while the other remains largely unexplored. This historical focus on fear learning and extinction has inadvertently left the neurobiology of trauma-related guilt, shame, and sadness in the dark. The team’s hypothesis suggests that treatments targeting the brain’s fear centers may be ineffective for emotional pain because they are engaging the wrong neural pathways. This explains why some individuals benefit from existing therapies while others do not, highlighting a critical gap in the scientific puzzle.

The link between these two profiles and their separate origins was proven through a multi-stage research process. The first study utilized network analysis on a sample of 838 individuals to statistically identify the two separate symptom clusters of fear and emotional pain. The second, more telling study tracked 162 recent trauma survivors with neuroimaging. Brain connectivity patterns measured just one month post-trauma were able to predict the development of chronic fear symptoms over a year later. Critically, these same early brain patterns failed to predict the severity of emotional pain symptoms, providing strong evidence that these two forms of suffering originate from different neurobiological processes. Dr. John Krystal, a leading expert, commented on the significance of this work, explaining that neuroimaging provides an objective way to untangle subjective distress. He noted that the study links fear to arousal and nightmares, while emotional pain is more closely associated with depression-like symptoms and insomnia, confirming their distinct clinical presentations.

From Diagnosis to Dialogue a Framework for Personalized Treatment

The ultimate goal of this research is not to create a new diagnostic label or splinter PTSD into subtypes but to sharpen the clinical lens used to view each individual’s suffering. The findings provide a framework for clinicians to move beyond a checklist of symptoms and identify the primary driver of a patient’s distress. Is their life organized around avoiding the terror of the past, or are they trapped in a cycle of self-recrimination and sorrow? Answering this question is the key to developing a truly personalized treatment plan that addresses the root cause of their pain rather than just its surface-level manifestations. This refined understanding allows for a more nuanced dialogue between the clinician and the patient about the nature of their post-traumatic experience.

This distinction directly informs how therapy can be tailored to the true source of pain. For individuals with a predominantly fear-driven profile, the continued value of established methods like exposure-based therapies remains clear. These interventions are specifically designed to help the brain extinguish a conditioned fear response and learn that triggers are no longer dangerous. However, for the majority whose distress is rooted in emotional pain, a different approach is warranted. This may involve the greater use of therapies that directly target debilitating guilt and shame, such as trauma-informed Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), which helps restructure negative self-beliefs, or compassion-focused therapy, which aims to cultivate self-kindness and alleviate self-criticism.

This evolution in understanding represents a fundamental shift toward putting the individual’s lived experience at the forefront of care. It acknowledges that trauma is not a monolithic event with a single emotional outcome. As Dr. Ben-Zion powerfully concluded, the intention was to “bring the patient’s subjective emotional reality to the center of the scientific discussion.” By recognizing which emotional system—fear or pain—is driving a person’s distress, the field of mental health moved closer to offering more precise, effective, and deeply compassionate treatment. This new paradigm ensured that survivors were not only heard but were also given the therapeutic tools that best matched their unique and personal wound.