A bacterial infection that is considered treatable in a New York hospital could be diagnosed as dangerously resistant in a Berlin clinic, a discrepancy rooted not in biology but in the conflicting rulebooks used to interpret the same scientific data. This global inconsistency is quietly undermining the fight against antimicrobial resistance (AMR), a silent pandemic that, just seven years ago, was associated with nearly five million deaths worldwide. As invisible superbugs evolve faster than the systems designed to track them, the lack of a universal language for defining resistance is creating a dangerously fractured and unreliable picture of one of humanity’s greatest health threats.

When the World’s Watchdogs Can’t Agree Are We Underestimating a Global Killer

The effectiveness of antibiotics, a foundational pillar of modern medicine, is under severe threat from the rapid evolution of resistant microorganisms. The problem has escalated to alarming proportions, and while often perceived as an issue confined to healthcare settings, its true scope is far broader. The extensive use of antibiotics in human medicine, livestock, and agriculture has resulted in their widespread release into the natural environment. These antibiotic residues are now frequently detected in soils, rivers, and even groundwater systems, turning them into unintended incubators for resistance.

This environmental contamination creates a perfect storm for the evolution of superbugs. Even at low concentrations, antibiotic residues exert selective pressure, favoring the survival and proliferation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB). These environments become hotspots where bacteria can exchange resistance genes through a process known as horizontal gene transfer. This mechanism allows resistance traits to spread rapidly among different bacterial species, accelerating the development of multidrug resistance across entire ecosystems and creating a reservoir of formidable pathogens.

Beyond the Hospital Walls Why Environmental Resistance Is Everyone’s Problem

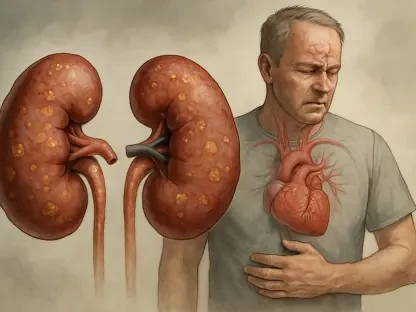

The proliferation of AMR in the environment is not an isolated ecological issue; it represents a direct and circulating threat to human health. Resistant bacteria and their genetic blueprints can cycle from the environment back into human populations through various pathways, including contaminated water, food supplies, and direct contact with soil. This “boomerang effect” means that an antibiotic that was once effective against a common infection may suddenly fail, not because of a breakdown in a hospital, but because resistance was acquired from an environmental source.

This insidious cycle has profound implications, leading to increased rates of treatment failure for once-manageable illnesses, longer and more complicated hospital stays, and a significant escalation in healthcare costs. As a result, comprehensive and reliable surveillance of AMR in the environment has shifted from being a niche ecological concern to an indispensable component of global public health security. Understanding how, where, and why resistance emerges in nature is now critical to protecting populations and preserving the efficacy of last-resort antibiotics.

The Measurement Maze How We Track an Invisible Enemy

Surveillance of AMR relies on two primary categories of methods: genetic-based approaches that read a microbe’s potential for resistance, and phenotypic approaches that observe its actual behavior. Genetic techniques, such as Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and metagenomic sequencing, offer unparalleled speed and sensitivity. They can screen large environmental samples for specific antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), providing results in a matter of hours. This capability is invaluable for creating early-warning systems and mapping the distribution of resistance determinants on a massive scale.

However, the presence of a resistance gene does not always guarantee that a bacterium will exhibit resistance. The gene may not be expressed, meaning the antibiotic could still prove effective. This creates a critical gap between genetic potential and real-world threat. Furthermore, metagenomic analysis of environmental samples can inadvertently capture human genetic material, raising complex ethical and privacy concerns that hinder the open sharing of data essential for global collaboration.

In contrast, phenotypic methods directly measure a bacterium’s ability to survive in the presence of an antibiotic. By determining the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)—the lowest antibiotic dose that prevents bacterial growth—these tests provide a definitive measure of resistance. Though considered the gold standard for their accuracy, traditional methods like broth microdilution are slow and labor-intensive. While newer technologies such as flow cytometry and microfluidics offer rapid, high-resolution results, their high cost and technical complexity limit their use to well-funded, specialized laboratories, leaving much of the world reliant on older, slower techniques.

A Tale of Two Standards The Data Distortion at the Heart of the Crisis

Obtaining a raw MIC value is only half the battle; this number must be interpreted to become clinically useful. This is achieved using “breakpoints,” which are predefined concentration thresholds that classify a bacterium as “Susceptible,” “Intermediate,” or “Resistant.” These classifications guide treatment decisions for individual patients and are aggregated to track resistance trends for entire populations. The problem is that the world’s two leading authorities—the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) in the United States and the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST)—do not use the same breakpoints.

These organizations employ different philosophies to set their thresholds. CLSI often maintains a broader “Intermediate” category to give clinicians flexibility, suggesting a drug might work at a higher dose. EUCAST, however, has moved to a more definitive framework, redefining its equivalent category to mean “Susceptible, Increased Exposure.” These subtle but significant differences in interpretation mean the same MIC value can yield conflicting classifications. For example, an E. coli isolate tested against the antibiotic ciprofloxacin could be labeled “susceptible” by CLSI standards but “resistant” under EUCAST guidelines.

This discrepancy has created a state of global data chaos. A patient’s prescribed treatment could vary dramatically depending on which country’s standard was used for their lab test. At a global surveillance level, this inconsistency generates so much statistical noise that it becomes nearly impossible to compare resistance data between regions, accurately track the international spread of a new superbug, or draw clear, evidence-based lines between environmental pollution and clinical outbreaks. The world is trying to solve a puzzle with pieces that do not fit together.

Forging a Unified Language to Fight a Common Foe

The consequences of this fractured data landscape are severe. Without a globally harmonized system for testing and interpretation, the capacity to monitor and control AMR was fundamentally compromised. Inconsistent data could lead policymakers to either underestimate a looming threat or misallocate critical public health resources based on a distorted picture of reality. For clinicians on the front lines, ambiguous or conflicting reports could reinforce the practice of prescribing broad-spectrum antibiotics, inadvertently fueling the very cycle of resistance they aim to break.

The analysis ultimately revealed that a standardized breakpoint system was not just an academic goal but an urgent global imperative. Such a framework would have enabled laboratories worldwide to speak a common language, transforming fragmented data into comparable and actionable intelligence. A harmonized system would have enhanced the quality of treatment decisions, facilitated the early detection of dangerous resistance trends, and finally allowed researchers to build the robust, evidence-based links between environmental AMR and public health outcomes that were so critically needed. Overcoming the AMR crisis demanded a unified front, built on a foundation of consistent interpretation, accessible monitoring tools, and international collaboration.