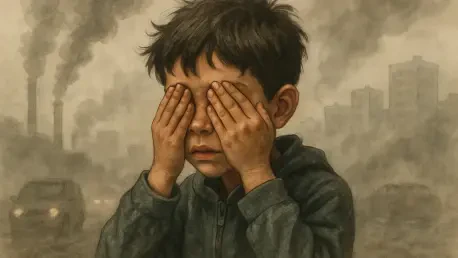

I’m thrilled to sit down with Ivan Kairatov, a renowned expert in environmental health and vision science, whose groundbreaking work has shed light on the critical link between air quality and children’s eyesight. With a deep background in biopharma and a passion for leveraging technology to address public health challenges, Ivan has been at the forefront of research exploring how pollution impacts young eyes and how cleaner air can make a transformative difference. In this conversation, we dive into the surprising connections between air pollution and vision problems like myopia, the innovative methods used to uncover these links, and practical steps to protect kids’ eyesight for a healthier future.

Can you walk us through the key findings on how air pollution affects children’s eyesight?

Absolutely, Jan. The research we’ve been working on shows a clear connection between air pollution and poorer vision in kids, particularly an increased risk of myopia, or short-sightedness. Pollutants like nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and fine particulate matter (PM2.5) seem to play a big role. These tiny particles can cause oxidative stress and inflammation on the ocular surface of the eye, which over time may contribute to vision issues. It’s especially concerning for children because their eyes are still developing, making them more vulnerable to environmental stressors like polluted air.

What makes myopia such a growing concern, especially in certain regions of the world?

Myopia has become a major public health issue globally, with rates skyrocketing to 80-90% among school-leavers in parts of East Asia. A big driver is the modern lifestyle—kids spending more time on screens and less time outdoors in natural light, which is crucial for healthy eye development. Add to that genetic factors, like having parents with myopia, and environmental challenges like air pollution, and you’ve got a perfect storm. In densely populated urban areas, where air quality tends to be worse, the problem is even more pronounced, which is why we’re seeing such high numbers in those regions.

How did your research team uncover the link between cleaner air and improved vision in kids?

We conducted a large study with about 30,000 students in Tianjin, China, ranging from primary to high school age. We measured their uncorrected visual acuity and collected detailed data on air quality, like levels of NO2 and PM2.5, alongside other factors such as family history of myopia, lifestyle habits, and even sleep patterns. What made this study unique was our use of machine learning to analyze these complex datasets. This approach helped us see how all these factors interact and pinpoint the specific impact of air pollution on vision, showing that cleaner air could indeed lead to measurable improvements.

Why do younger children, like those in primary school, seem to benefit more from cleaner air compared to older students?

That’s a fascinating observation from our findings. Younger kids, especially in primary school, showed greater improvements in vision when exposed to cleaner air—about double the average improvement seen across all age groups. We believe this is because their eyes are still in a critical stage of development, so they’re more sensitive to environmental changes. Reducing pollution at this stage can have a more significant protective effect, potentially slowing the onset or progression of myopia before it becomes more severe as they age.

Can you elaborate on the potential impact of reducing air pollution, based on the scenarios your study explored?

Certainly. In our simulations, we looked at what would happen if we reduced levels of key pollutants like NO2 and PM2.5. On average, we saw an improvement in uncorrected visual acuity by about 0.04 units across the entire group. But for primary school kids, the improvement was even more striking—around 0.09 units. This suggests that cleaner air doesn’t just help; it can have a substantial effect, especially for younger children whose vision is still adaptable. It’s a strong argument for prioritizing air quality interventions early on.

What are some practical ways to reduce kids’ exposure to air pollution and protect their eyesight?

There are several actionable steps we can take. One is installing air purifiers in classrooms, which can significantly cut down on indoor exposure to pollutants. Another idea is creating clean-air zones around schools—areas with restricted traffic or enhanced green spaces to lower pollution levels. These measures can create safer environments for kids to learn and play in, reducing the daily burden on their eyes. Beyond that, encouraging outdoor time in cleaner, greener spaces can also help, as natural light is beneficial for vision health.

What’s your forecast for the future of children’s vision health if we continue to improve air quality?

I’m cautiously optimistic, Jan. If we can sustain efforts to improve air quality—through policy changes, urban planning, and community initiatives—I believe we could see a meaningful reduction in the prevalence of myopia and other vision issues in children over the next few decades. The data shows that even small reductions in pollution can have outsized benefits, especially for younger kids. But it’s going to take a collective push—governments, schools, and families working together—to make clean air a priority. If we do that, we’re not just protecting eyesight; we’re investing in healthier generations overall.