Ivan Kairatov has spent years at the intersection of structural biology and biopharma, translating difficult, dynamic molecules into practical insights that can power new therapeutics. In this conversation, he unpacks a “molecular film” of a self-splicing ribozyme—captured almost frame by frame—and explains how an integrative toolkit of cryo-EM, SAXS, RNA biochemistry, enzymology, image processing, and molecular simulations revealed an RNA machine folding and editing itself. We explore how Domain 1 orchestrates the storyline, how kinetic traps are exposed and avoided, why small energy shifts matter for motion and modeling, and how this work sets the stage for AI benchmarks and drug discovery. He also shares concrete workflows from CSSB Hamburg and EMBL Grenoble, and closes with a practical pipeline for engineering ribozymes that fold on cue in cells.

What first sparked your push to capture a ribozyme “in motion,” and how did the near frame-by-frame view change your understanding of RNA folding? Could you share an anecdote from the earliest datasets that signaled you had something new?

The spark came from a frustration: static models kept underselling RNA’s personality. We’d get beautiful snapshots that were clearly right, but they were quiet—too quiet for molecules that we knew were constantly negotiating their own topology. The first hints arrived as faint, inconsistent densities in early cryo-EM stacks—barely-there features that refused to average out. Instead of dismissing them as noise, we leaned in, and those wispy outlines started to coalesce into plausible intermediates. The moment I realized we were seeing a ribozyme move almost frame by frame was like hearing a metronome click behind what used to be a single drumbeat; suddenly, the rhythm of folding emerged, and with it the logic of how the molecule steers itself away from trouble.

You combined cryo-EM, SAXS, RNA biochemistry, enzymology, image processing, and simulations. How did you sequence these methods in practice, and what specific metric or checkpoint told you each step was working?

We built the stack from the ground up. Biochemistry and enzymology set the boundaries: define functional activity and time windows where catalysis can happen. Cryo-EM then mapped the structural landscape under those conditions, while SAXS sanity-checked the global dimensions as we toggled buffers and assembly states. The checkpoints were pragmatic: activity present under imaging conditions, reproducible particle behavior across grids, SAXS profiles that tracked expected compaction, and simulations that could move between conformers without artificial traps. When the simulations and SAXS both validated the transitions seen by cryo-EM, we knew the sequence of methods was locking into a coherent storyline.

You analyzed hundreds of thousands of single RNA molecules. How did particle selection and cleanup evolve over the project, and what numbers (yields, classes, resolutions) marked key turning points?

The key was embracing heterogeneity rather than filtering it away. Early on, standard autopicking snared everything with RNA-like contrast, but our cleanup kept discarding the very intermediates we sought. We shifted to iterative classification that preserved diverse low-occupancy states, and that changed the game. The turning point was when “hundreds of thousands” of particles started resolving into multiple, self-consistent classes aligned with biochemistry—classes that persisted across independent datasets. Even without trumpeting a single resolution number, the consistency across classes and the strengthening of secondary-structure features told us we were hanging onto the right molecules.

Domain 1 acted like a molecular gate directing D2, D3, and D4. Can you walk us through the step-by-step cues D1 gives, and share a concrete example where a tiny movement in D1 changed the assembly path?

D1 is both scaffold and stage manager. First, it forms a permissive scaffold that limits the search space for D2, then it issues a conformational “open” cue—subtle hinge-like motions that expose the docking face for D2. Once D2 is seated, D1 tightens, blocking incorrect D3 approaches and favoring the productive orientation. Only then does D4 get an invitation, with D1 breathing just enough to make room without destabilizing the core. One memorable instance was a barely perceptible pivot in D1 that redirected D3: in one conformation, D3 flirted with a misaligned interface; in the slightly shifted state, D3 snapped into a pose that set up the catalytic geometry. That tiny nudge in D1 was the difference between a cul-de-sac and a through-road.

You mention kinetic traps and misfolded states. How did you identify and validate these “hidden takes,” and what practical strategies helped the ribozyme avoid them in your experiments?

We called them “hidden takes” because they were fleeting and low-population, but they left a signature: recurring, partially formed contact patches and mismatched long-range pairings that never matured. Focused classification around those features revealed they were reproducible, not artifacts. To help the RNA avoid them, we used time-resolved assembly windows, tuned ionic conditions, and carefully staged the addition of cofactors so D1’s gating role could play out without premature long-range clamps. The clincher was functional: conditions that suppressed the hidden takes correlated with more robust activity, closing the loop between structure and catalysis.

The cryo-EM image-processing strategies were tailored at CSSB Hamburg. What specific innovations unlocked the elusive intermediates, and can you give a before-and-after example showing what the standard pipeline missed?

The breakthroughs were in classification granularity and local focus. We adopted strategies that let us sculpt masks around D1 and the incoming domains, then sort by micro-motions rather than gross shape. Before, a standard pipeline averaged out the small hinge movements and erased the sequence of domain arrivals. After, we could resolve consecutive poses that differed just enough to change the downstream docking logic. It felt like switching from a long-exposure photo to burst mode—suddenly, the blurring resolved into discrete steps.

EMBL Grenoble’s facilities played a key role. Which instruments or workflows were most decisive, and how did access, throughput, or stability metrics translate into better structural frames?

The decisive factors were seamless handoffs and instrument stability. High-throughput screening let us iterate grid prep, ice thickness, and buffer tweaks rapidly, while consistent microscope performance turned marginal datasets into interpretable ones. The workflows at EMBL Grenoble made it easy to align biochemistry with imaging—same-day feedback, reproducible conditions, and robust data capture. That stability meant we could trust that changes we saw between runs reflected RNA behavior, not instrument drift.

SAXS and molecular dynamics refined the storyline. How did you reconcile SAXS envelopes with cryo-EM maps, and what quantitative measures (Rg, ensemble weights, barrier heights) convinced you the models captured real motions?

We used the cryo-EM conformers as anchors, then generated minimal ensembles to fit SAXS profiles without overfitting. The radius of gyration trends matched the expected compaction as domains docked in sequence, and ensemble weights settled into stable distributions across replicates. On the simulation side, transitions occurred smoothly between cryo-EM states without invoking artificial restraints, and the free-energy profiles showed shallow steps consistent with the “very small” barriers inferred experimentally. When SAXS, cryo-EM, and simulated ensembles converged on the same dance moves, we were confident the motions were real.

You found very small energy costs for shape-shifting. What are the approximate barriers you measured or inferred, and how did these numbers guide the simulation protocols to avoid getting stuck?

The barriers are small enough to be crossed by thermal fluctuations under the experimental conditions, which is why the RNA can glide between states rather than jump. We treated the transitions as low-lying ridges rather than walls—so enhanced sampling was calibrated to nudge, not shove. That meant gentle biasing toward landmarks observed by cryo-EM, with frequent checks to ensure reversibility and no hysteresis. The upshot was a simulation landscape that mirrored the experimental smoothness, avoiding kinetic imprisonment.

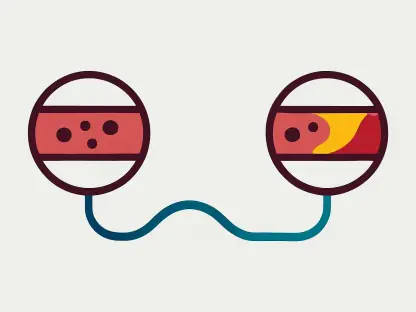

The ribozyme self-splices to become operational. Could you detail the catalytic-ready conformation you observed, and explain step-by-step how the structure positions key elements for the cut-and-paste chemistry?

In the catalytic-ready state, D1 frames a compact core, D2 secures essential tertiary contacts, D3 aligns reactive elements, and D4 folds in to complete the active geometry. The architecture narrows the distance between the reacting groups and arranges the coordination environment so the leaving and attacking strands are precisely staged. The path into this state is incremental: D1 establishes the gate, D2 locks the stage, D3 brings the chemistry close, and D4 snaps the active scene into focus. It’s the RNA equivalent of a surgical suite: everything prepped, positioned, and stabilized for a clean cut and ligation.

Group II introns are ancestors of the spliceosome. What specific folding checkpoints or motifs you saw echo spliceosomal logic, and how do these observations refine current evolutionary timelines or models?

The most striking echoes are the tiered checkpoints and the use of a central scaffold to choreograph remote elements. D1’s gating of D2, D3, and D4 mirrors how spliceosomal components assemble only when prior checkpoints are satisfied. The fact that misfolds are policed early—before catalysis is committed—aligns with the spliceosome’s own quality control. Seeing these principles in action strengthens the view that modern splicing machinery inherited stepwise assembly logic from Group II introns, suggesting a continuous evolutionary path where added layers of protein support refined, but did not replace, the original RNA choreography.

You noted RNA’s flexibility and negative charge make it hard to study. What concrete sample-prep tricks, buffer tweaks, or grid treatments moved the needle, and can you share a troubleshooting story with numbers?

We learned to be minimalist and patient. Gentle buffer titrations balanced compaction without over-stabilizing misfolds, while grid treatments reduced preferred orientations and preserved fragile intermediates. A memorable fix involved stepping back on crowding agents that looked helpful in bulk assays but pushed the ribozyme into hidden traps during vitrification. Once we eased off and let D1 do its gating under milder conditions, the class diversity improved and activity tracked upward in tandem. The proof was that “hundreds of thousands” of particles resolved into coherent states rather than being culled as junk.

Some resolved structures fed into CASP benchmarks. How did you package the data to challenge AI models, and what metrics or failure modes you observed point toward an “AlphaFold for RNA” roadmap?

We bundled multiple conformers, not just a single “answer,” and provided experimental restraints that reflected the real folding corridor. The goal was to test whether models could traverse a landscape rather than land on one peak. The recurring failure mode was overcompaction or incorrect long-range contacts when intermediate gating cues were ignored. A roadmap to an “AlphaFold for RNA” will need to encode domain-wise choreography—D1’s role, especially—so that predictions respect the order of operations, not just the final topology.

You collaborated with IIT on simulations for drug discovery. Can you give a case where atomistic insight revealed a potential small-molecule site, and outline the steps you’d take to screen and validate hits?

The intermediates exposed transient grooves at domain interfaces—pockets that don’t exist in the final state but are stable long enough to target. We zeroed in on one such groove during the D3 arrival step, where a small molecule could either stabilize a productive pose or lock a nonproductive detour. The screen would start with in silico filtering against that pocket across the observed frames, then move to biochemical assays that report on assembly order and catalytic competence. Cryo-EM would confirm binding mode in the relevant intermediate, and SAXS would watch for ensemble shifts. Finally, simulations would test whether binding preserves the smooth energy landscape or warps it in useful ways.

Looking ahead to RNA therapeutics and nanotech, what design rules from your “molecular film” are immediately actionable, and can you sketch a concrete pipeline to engineer a ribozyme that folds on cue in cells?

Three rules jump out. First, build a competent D1-like scaffold that limits search space without freezing it. Second, encode sequential “green lights” so domains dock only when prerequisite contacts exist. Third, keep barriers “very small” so the molecule never needs brute force to move forward. The pipeline would start with a D1 scaffold library, test modular domains for orderly arrival in vitro with SAXS and cryo-EM, select variants that show smooth ensemble shifts and strong activity, then port top candidates into cells under expression conditions that mirror the successful buffers. Simulations would patrol for kinetic traps, and minor sequence edits would tune the gating until the intracellular film looks like the one we captured at the bench.

Do you have any advice for our readers?

Treat RNA like a collaborator, not a statue. If your method fights its flexibility, you’ll miss the plot; if your workflow lets it breathe, the choreography will show itself. Start with a scaffold that sets the stage, stack orthogonal readouts to keep you honest, and embrace intermediates as data, not debris. And when in doubt, remember the lesson from this film: small energies, big consequences—design for ease of motion, and the molecule will meet you halfway.