Today we’re joined by Ivan Kairatov, a biopharma expert at the forefront of medical diagnostics. For decades, the cornerstone of blood analysis has been the microscope, a tool reliant on human interpretation. But what if we could teach a machine to see the invisible signs of disease in a single blood cell, long before a human eye could? We’ll be exploring a groundbreaking technology that uses polarized light and artificial intelligence to do just that, discussing how this method provides objective, quantitative data, the challenges of training a machine to be a diagnostician, and what this leap in technology means for the future of detecting and managing conditions like malaria and diabetes.

The article highlights that traditional microscopy is time-consuming and subjective. Could you walk us through how your DMMP method overcomes these limitations and what makes its quantitative measurements more reliable than a trained expert’s visual inspection of a blood sample?

Absolutely, and that’s really the core of the problem we set out to solve. When you rely on traditional optical microscopy, you’re fundamentally limited by human subjectivity. A highly experienced pathologist might look at a blood smear and say, “These cells look misshapen,” but that’s a qualitative judgment. Their colleague might describe it slightly differently, and a less experienced technician might miss the subtle deformation altogether. It’s also incredibly slow; you’re manually scanning and assessing cells one by one. Our dual-angle Mueller matrix polarimetry, or DMMP, completely removes that subjectivity. Instead of relying on a human interpretation of an image, we are measuring the physical interaction between light and the cell itself. We shine polarized light on a cell and measure precisely how its polarization state changes. This change is directly tied to the cell’s physical properties. We then distill this complex interaction down into six concrete, numerical parameters that describe things like size, shape, and even refractive index. So, instead of a subjective opinion, you get a hard data point. This is far more reproducible and reliable because the measurement is based on physics, not perception, allowing us to detect minute abnormalities with consistent accuracy every single time.

Your team’s technology analyzes a cell’s “polarization signature” to extract six feature parameters. Could you explain what these signatures represent and share an anecdote from your research where one of these specific parameters revealed a subtle cell deformation that was previously missed?

Think of a cell’s polarization signature as its unique fingerprint, but written in the language of light. Every cell, based on its morphology and internal structure, alters light in a very specific way. Our DMMP system is designed to read that fingerprint. The six feature parameters are the most important characteristics of that fingerprint, quantitatively describing the cell’s most telling features. For instance, some parameters relate directly to the overall shape and volume, while others give us insights into the texture and composition of the cell’s surface. I vividly remember one experiment where we were applying osmotic stress to a sample of healthy red blood cells, which mimics certain disease states. Visually, under a standard microscope, the cells looked perfectly fine in the initial stages. However, our DMMP system immediately picked up a consistent, subtle shift in one of the parameters related to the cell’s surface characteristics. It was a tiny deviation, but it was statistically significant across hundreds of cells. This turned out to be the very first sign that the cell membranes were beginning to weaken, long before they actually started to deform or rupture. It was a powerful moment for us because it proved our system could see the precursor to damage—a biological whisper that would be completely inaudible to traditional methods.

You achieved over 94% accuracy distinguishing cell types using a Random Forest classifier. What were the biggest challenges in training this machine learning model, and can you describe the step-by-step process of how it uses polarization data to classify a cell as healthy or abnormal?

Achieving that 94% accuracy was a major milestone, but it was certainly not a simple plug-and-play process. The single biggest challenge in training any machine learning model is the quality of the training data. We had to create a meticulously curated library of thousands upon thousands of cells, including perfectly healthy ones and cells that we had altered in very specific ways to mimic various pathologies. Each one had to be flawlessly measured by the DMMP system to ensure our model wasn’t learning from noisy or inaccurate data. The process itself is quite elegant. First, a single cell flows through our system and is illuminated by the polarized light. The detector captures its unique polarization signature. Our software then instantly calculates the six key feature parameters from that signature. These six numbers become the input for our Random Forest classifier. A Random Forest is essentially a large committee of individual “decision trees.” Each tree looks at the cell’s six parameters and makes its own independent judgment: “healthy” or “abnormal.” Finally, the model tallies the votes from all the trees. If the vast majority vote “abnormal,” the cell is classified as such. This ensemble approach is what makes it so robust and accurate, as it prevents one faulty line of reasoning from skewing the final result.

The article mentions your technology is label-free and can analyze hundreds of cells per minute. How does this high-throughput capability compare to traditional methods in terms of time and cost, and what practical steps are needed to integrate this system into routine clinical blood screenings?

The difference in throughput is staggering. A skilled hematologist might spend 30 to 60 minutes preparing a slide with fluorescent stains, and then another significant block of time meticulously scanning it under a microscope to identify and count abnormal cells. In that same timeframe, our label-free system can analyze tens of thousands of cells. By processing hundreds of cells per minute, we can generate a statistically powerful profile of a patient’s blood in a matter of minutes, not hours. Because we don’t need fluorescent labels or complex preparation, the cost per test is dramatically reduced, both in terms of materials and expert labor. To integrate this into routine clinical screenings, the path involves a few key steps. First is engineering: we need to package the technology into a robust, compact, and user-friendly benchtop device that a standard lab technician can operate with minimal training. Second, we must conduct extensive clinical trials to validate its efficacy against current gold-standard methods across a wide range of blood disorders. And finally, we need to navigate the regulatory approval process to demonstrate its safety and reliability for diagnostic use. The goal is a “sample-in, answer-out” system that seamlessly fits into the existing clinical workflow.

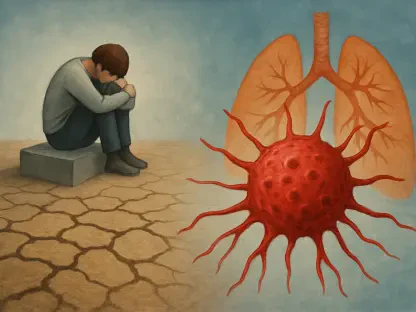

What is your forecast for how this technology will change the way we diagnose and monitor blood-related disorders like malaria and diabetes over the next decade?

My forecast is that this technology will help shift the paradigm from reactive diagnosis to proactive and personalized health monitoring. For a disease like diabetes, we currently monitor glucose levels, but that doesn’t tell us about the cumulative damage to cells. Imagine a future where a diabetic patient’s treatment is fine-tuned not just based on their sugar levels, but on how their red blood cells are structurally responding to therapy. We could literally see their cells becoming healthier in real time. For infectious diseases like malaria, which deforms red blood cells, this could be a game-changer for point-of-care diagnostics in remote regions. A portable, label-free device could provide a rapid, accurate diagnosis without needing a full lab and a trained microscopist. Over the next decade, I see this moving beyond a simple “healthy vs. sick” classification. We’ll be able to use these detailed polarization signatures to create personalized health baselines for individuals, tracking subtle changes over years to predict disease risk long before clinical symptoms ever appear. It’s about giving doctors a much clearer, more detailed, and earlier picture of what’s happening inside our bodies at the cellular level.