The humble chest X-ray, a diagnostic workhorse for over a century, is undergoing a remarkable transformation, revealing hidden health insights that extend far beyond the thoracic cavity. A groundbreaking study demonstrates how artificial intelligence can empower this ubiquitous and low-cost imaging modality to detect signs of hepatic steatosis, commonly known as fatty liver disease—a condition affecting an estimated 25% of the global population. This innovation represents a significant paradigm shift, moving the chest radiograph from a tool for targeted diagnosis to a platform for broad, opportunistic screening. By training a deep learning model to identify subtle patterns invisible to the human eye, researchers have unlocked the potential to flag at-risk individuals during routine medical exams, creating a new pathway for early intervention without adding to patient burden or healthcare costs. This approach could redefine preventative medicine, particularly in settings where more advanced diagnostic tools like CT or MRI are not readily available.

A New Frontier in Opportunistic Screening

The fundamental premise of this research lies in the immense, untapped potential of existing medical data. Chest X-rays are among the most frequently performed imaging procedures globally, and each scan incidentally captures the upper portion of the abdomen, including the liver. Recognizing this, a team led by Dr. Daiju Ueda of Osaka Metropolitan University posed a critical question: could an AI model be trained to analyze these images and identify individuals with fatty liver disease? The rationale is compelling, as early detection of hepatic steatosis is crucial for managing its progression and preventing more severe liver damage. The goal was to develop a system for “opportunistic screening,” a method that leverages routine clinical activities to check for other conditions. Such a tool could add significant value to the healthcare system by identifying at-risk patients who could then be directed toward more definitive assessments, all without requiring new appointments, additional radiation exposure, or increased costs for the patient or provider.

To bring this concept to life, the researchers employed a robust and meticulous methodology to develop and train their AI model. They utilized a retrospective collection of 6,599 posteroanterior chest X-rays from over 4,400 patients across two different institutions, ensuring a diverse dataset. The “ground truth” for the AI’s training—the definitive label of whether a patient had fatty liver disease—was established using controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) exams, a non-invasive and accurate method for quantifying liver fat. The core of the system was a commercial convolutional neural network (CNN), a type of AI architecture highly effective at image recognition. This model was first pre-trained on a massive general image dataset before being fine-tuned specifically for the task of spotting steatosis on radiographs. During this fine-tuning phase, the model was only given the X-ray images and their corresponding labels, forcing it to independently learn the subtle radiographic signatures correlated with the disease.

From Pixels to Predictions

Once trained, the deep learning model was subjected to rigorous testing to validate its performance, and the results were consistently strong. In an internal test set composed of data from the same institution as the training data, the model achieved an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.83, a key metric indicating its excellent ability to distinguish between patients with and without the disease. Its performance was further characterized by an accuracy of 77%, a sensitivity of 68%, and a specificity of 82%. More importantly, when evaluated on an external test set from an entirely different institution—a crucial test of its generalizability—the model maintained a high level of performance. It achieved an AUC of 0.82 and uniform values of 76% for accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity. This demonstrated that the AI’s learned knowledge was not specific to one hospital’s equipment or patient population but was robust enough to be applied more broadly, a critical requirement for any tool intended for widespread clinical use.

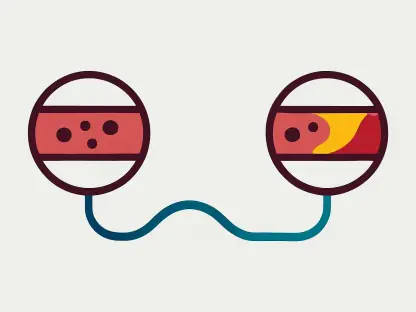

A common concern with AI in medicine is the “black box” problem, where it is unclear how the model arrives at its conclusions. To address this and build confidence in their model’s diagnostic process, the researchers employed saliency maps. These maps are visualization tools that highlight the specific regions of an X-ray image that the AI focused on most heavily when making a prediction. An analysis of these maps provided compelling evidence that the model was behaving as intended. In 74.2% of the external test images, the saliency maps correctly pinpointed the anatomical area at or below the diaphragm, which is consistent with the location of the liver. This verification step was crucial, as it confirmed that the AI was learning clinically relevant features related to liver tissue rather than relying on irrelevant artifacts or spurious correlations in the images. This added a vital layer of transparency and trust, suggesting the model’s predictions were based on sound, anatomically-grounded reasoning.

The Path to Clinical Integration

The successful development of this AI model marked a significant step forward in repurposing a mature medical technology. Dr. Ueda and his team stressed that the tool was not designed to replace definitive diagnostic methods for liver disease but rather to function as an intelligent triage system that could “raise suspicion” during routine care. Its clinical role was envisioned as a way to efficiently identify individuals who would benefit most from dedicated liver imaging or lifestyle counseling, thereby optimizing the use of healthcare resources. This initial study was unique as the first to demonstrate this capability on standard chest radiographs with external validation. Before this technology could be implemented in clinical practice, however, the researchers noted that several critical steps remained. These included conducting prospective, multi-center trials to confirm its effectiveness in real-world settings, calibrating its performance across diverse patient populations, and studying the best methods for integrating its automated alerts into existing clinical workflows to ensure it aids, rather than disrupts, patient care.