For decades, the story of dementia has been told through the lens of the wreckage it leaves behind, focusing on the sticky protein plaques that litter the brains of patients. But what if the true villain is not the aftermath of the battle, but the very first shot fired—a preemptive act of cellular self-destruction that initiates the entire cascade of devastation? A landmark collaborative study has provided the first direct molecular evidence that a specific form of programmed cell death, known as ferroptosis, can be a primary driver of neurodegeneration, fundamentally altering the scientific community’s understanding of how these diseases begin and progress.

This research, spearheaded by teams from Helmholtz Munich, the Technical University of Munich, and LMU University Hospital Munich, points to a new direction in the quest for effective treatments. By identifying a fundamental protective mechanism within nerve cells and pinpointing how its failure leads to their demise, the findings unlock potential therapeutic avenues not just for rare childhood dementias, but also for more common conditions like Alzheimer’s disease.

Shifting Focus from Cellular Debris to the Initial Spark

The dominant theory in neurodegeneration research has long centered on the accumulation of protein aggregates, such as amyloid-beta plaques and tau tangles. This “amyloid hypothesis” has guided the development of countless therapeutic strategies, many of which have aimed to clear this protein debris from the brain. While these aggregates are undeniably a hallmark of diseases like Alzheimer’s, their precise role as a cause versus a consequence has been a subject of ongoing debate, especially as plaque-clearing drugs have shown mixed results.

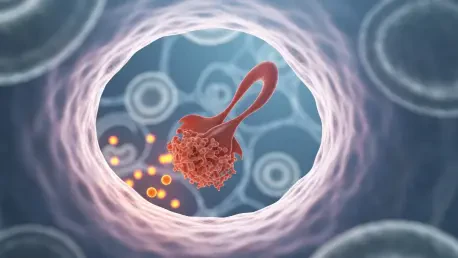

The new findings challenge this paradigm by suggesting that the critical event may occur much earlier, at the level of the cell membrane. This research places the spotlight on ferroptosis, a form of regulated cell death triggered by the iron-dependent accumulation of oxidized fats, or lipid peroxides. When these harmful molecules build up, they inflict catastrophic damage on the cell’s outer boundary, leading to its rupture and death. This perspective reframes the problem: instead of just cleaning up the rubble of dead neurons, the key may be to prevent the initial explosion.

A Cellular Guardian and Its Newly Found Achilles Heel

At the heart of this discovery is a crucial protective enzyme called glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4). This protein acts as the primary guardian of neurons, defending them against the lethal chain reaction of ferroptosis. The research team sought to understand the precise mechanics of this protection and uncovered a previously unknown structural feature of the GPX4 enzyme: a short protein loop that functions like a fin on a surfboard.

This “fin” allows the enzyme to anchor itself directly into the inner surface of the neuronal cell membrane. From this embedded position, GPX4 can efficiently “surf” along the membrane, seeking out and neutralizing dangerous lipid peroxides before they can cause irreversible harm. The breakthrough’s origin, however, was a tragic one. The investigation was sparked by the cases of three children in the United States suffering from a rare and aggressive form of early-onset dementia. Genetic analysis revealed they all shared an identical mutation, R152H, in the gene that codes for GPX4, a mutation that directly targets this critical fin-like loop.

This single point mutation prevents the GPX4 enzyme from properly inserting into the cell membrane. Without its anchor, the guardian protein is unable to perform its patrol duties effectively. As a result, lipid peroxides accumulate unchecked, leading to membrane damage, the initiation of ferroptosis, and the widespread death of nerve cells. This provided the first direct link between a failure in this specific anti-ferroptotic mechanism and a devastating human neurodegenerative disease.

Recreating a Rare Disease in the Laboratory

To confirm that this genetic flaw was the direct cause of the disease, scientists embarked on a multi-stage validation process. They first obtained cell samples from one of the affected children and used advanced reprogramming techniques to turn them into induced pluripotent stem cells. These versatile cells were then coaxed to develop into cortical neurons and complex, three-dimensional brain organoids—miniature brain-like structures that mimic early human brain development in a dish.

This innovative “disease-in-a-dish” model allowed researchers to observe the consequences of the R152H mutation in living human neurons. It provided a controlled environment to study the molecular cascade of events, confirming that the defective GPX4 led to increased vulnerability to ferroptosis. However, to understand the disease’s progression within a complete biological system, they needed an animal model.

The team engineered mice with the exact same R152H mutation in their GPX4 gene, impairing the enzyme’s function specifically in nerve cells. The results were stark and closely mirrored the human patients’ condition. The mice gradually developed severe motor impairments, and examination of their brains revealed significant neuron loss in the cortex and cerebellum, alongside strong signs of neuroinflammation—a common feature of many neurodegenerative disorders.

An Unexpected Molecular Link to Alzheimer’s Disease

The study delivered its most profound surprise when researchers analyzed the full spectrum of proteins in the brains of their mouse model. This proteomic analysis revealed which proteins had changed in abundance due to the impaired GPX4 function. When they compared this molecular signature to existing data from human brain tissue, they found an astonishing parallel.

The pattern of protein dysregulation in the mice with defective ferroptosis protection was remarkably similar to the protein profiles seen in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Numerous proteins known to be either elevated or depleted in Alzheimer’s showed the exact same changes in the experimental model. This powerful correlation suggests that ferroptotic stress is not limited to a single rare disease but may be a fundamental, underappreciated mechanism contributing to the pathology of one of the world’s most common forms of dementia.

Charting a New Therapeutic Path Against Neurodegeneration

These findings represent a potential paradigm shift, suggesting that membrane damage from ferroptosis could be the true first domino to fall in the complex cascade of neurodegeneration. According to first author Dr. Svenja Lorenz, the evidence strongly indicates that ferroptosis can be a primary driving force behind neuronal death, not merely a side effect of other pathological processes. This reorients the search for treatments away from solely managing protein aggregates and toward preserving the integrity of the neuronal membrane.

While this work is still foundational, it opens a promising new front in the war against dementia. In their experiments, the scientists showed that the cell death in both their lab-grown neurons and the mouse model could be slowed by applying chemical compounds that specifically inhibit the ferroptosis pathway. Co-first author Dr. Tobias Seibt described this as a vital “proof of principle,” though he emphasized it is not yet a ready-made therapy. The long-term goal is to develop sophisticated strategies, whether genetic or molecular, to reinforce this natural cellular defense system, offering hope for a future where dementia can be stopped before it truly begins.

The culmination of nearly 14 years of intensive, collaborative research provided a remarkable bridge between a minute structural detail on a single enzyme and a devastating human disease. This journey not only illuminated the cause of a rare childhood dementia but also cast a new light on the mechanisms potentially driving more widespread neurodegenerative conditions. The discovery shifted the scientific narrative from a focus on downstream consequences, like protein plaques, to the initial, critical failure of a cell’s own protective machinery. It was a powerful demonstration that understanding the fundamental biology of cell death held the key to unlocking one of medicine’s most formidable challenges. This work established a vital new target for drug development, offering a concrete path toward therapies designed not just to manage symptoms, but to preserve the very foundation of neural health.