Today, we are joined by Ivan Kairatov, a biopharma expert at the forefront of technological innovation in medicine. With colorectal cancer ranking as the third most common cancer worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths, the medical community is urgently seeking better diagnostic tools. A recent meta-analysis of studies from 2020 to 2024 reveals that artificial intelligence is no longer a futuristic concept but a present-day reality, significantly boosting the speed and accuracy of colon cancer detection and offering new hope in the fight against this devastating disease.

Throughout our conversation, we will explore how AI is tangibly assisting physicians during live procedures like colonoscopies and the critical role of “Explainable AI” in building clinical trust. We will also delve into the technical specifics of AI tasks, such as segmentation, and discuss how they directly influence patient treatment plans. Finally, we will confront the major roadblocks—namely, data limitations and integration hurdles—that currently prevent these powerful tools from being universally adopted in hospitals.

Your study notes that AI enhances polyp detection during colonoscopies. Could you walk me through how an AI system assists a physician in real-time during this procedure, and what specific metrics show its performance over traditional methods?

Certainly. Imagine a gastroenterologist conducting their fourth or fifth colonoscopy of the day; fatigue is a real factor. As they navigate the colon, a live video feed is displayed on a monitor. The AI system analyzes this feed in real-time, frame by frame. When it identifies a suspicious area—perhaps a small, flat polyp that’s notoriously easy to miss—it places a colored box around it on the screen, alerting the physician. It’s like having a tireless second pair of eyes that is trained on millions of images. The performance metrics are compelling; studies consistently show that AI-assisted colonoscopies have a higher adenoma detection rate, which is the gold standard. We’re not just finding more polyps, but more of the specific pre-cancerous ones that matter, fundamentally improving the preventative power of the screening itself.

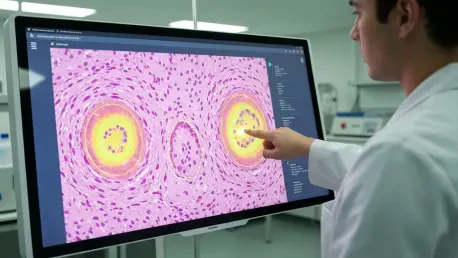

Professor Harous emphasizes that “Explainable AI” is essential for building clinician confidence. Can you give a practical example of how these systems explain their reasoning to a doctor and what that interaction between the AI and the medical professional actually looks like?

This is an absolutely crucial point, because doctors will not, and should not, trust a “black box.” A practical example can be found in histopathology. A pathologist places a tissue slide under a digital microscope, and the AI analyzes it. Instead of just giving a binary “cancer” or “no cancer” output, an explainable AI system highlights the specific regions of the slide that led to its conclusion. It might outline clusters of cells with abnormal nuclei or irregular gland structures, and in some advanced systems, it even provides a confidence score. This allows the pathologist to immediately zoom in on those areas and apply their own expertise. The interaction is a collaborative one; the AI acts as an incredibly powerful screening assistant, flagging areas of interest and providing its rationale, but the final diagnostic decision always rests with the human expert. It fosters trust by making the technology a transparent partner, not an opaque authority.

The meta-analysis reviewed 80 studies focused on four key tasks. Could you elaborate on the “segmentation” task specifically? Describe the process and explain how improving gland segmentation directly impacts precision staging and a patient’s treatment plan.

Segmentation is essentially the process of creating a highly precise digital outline of a specific feature on a medical image, like a tumor or individual glands within a tissue sample. Think of it as a meticulous, pixel-by-pixel tracing. In colon cancer pathology, the architecture of glands is a critical indicator of cancer grade. A well-differentiated, less aggressive tumor has glands that look relatively normal, while a poorly-differentiated, highly aggressive tumor has chaotic, malformed glands. An AI model can segment thousands of these glands in minutes, a task that would be painstakingly slow and subjective for a human. By accurately quantifying the shape, size, and distribution of these glands, the AI provides an objective measure of the tumor’s aggressiveness. This has a massive impact on precision staging, which in turn dictates the patient’s treatment plan—determining whether a patient needs aggressive chemotherapy after surgery or if the tumor is low-grade enough that surgery alone is sufficient.

The research identifies a critical gap regarding limited and homogeneous datasets. What are the specific risks of using these datasets when training diagnostic AI, and what concrete steps are needed to build the diverse, high-quality data required for widespread clinical use?

The risks are incredibly high and represent a major barrier to equity in healthcare. An AI model is only as good as the data it’s trained on. If a model is trained exclusively on data from a specific demographic at a single hospital, it can develop significant biases. It might be brilliant at detecting cancer in that population but fail spectacularly when used on patients of a different ethnicity, age, or even with different imaging equipment. The real-world risk is a missed diagnosis or a false positive, with devastating consequences for the patient. To fix this, we need a concerted global effort to build robust, diverse, and high-quality labeled datasets. This involves creating federated learning networks where models can be trained across multiple hospitals and countries without sensitive patient data ever leaving its source institution. It requires standardization of data collection and annotation, and it is an enormous logistical challenge, but it is absolutely essential for creating AI tools that are safe, effective, and equitable for everyone.

You state that most AI systems are still in labs due to integration challenges. What are the primary technical and workflow hurdles preventing their adoption into hospital information systems, and what would a successful, step-by-step integration process look like?

This is where the rubber meets the road, and unfortunately, where many promising technologies falter. The primary technical hurdle is interoperability. A hospital’s IT ecosystem is a complex web of legacy systems—electronic health records, imaging archives, and scheduling software—that were never designed to talk to a modern AI. Getting a new algorithm to seamlessly pull data from one system and display its results in another without crashing everything is a monumental task. The workflow hurdle is just as significant; a tool is useless if it adds ten clicks and five minutes to a doctor’s already-packed schedule. Successful integration must be gradual. It would start with a pilot study in a single department to work out the technical bugs and refine the user interface based on direct feedback from clinicians. The next step is a limited rollout to measure impact on diagnostic accuracy and efficiency. Only after rigorous validation and demonstration of clear value can it be scaled across the entire hospital system. It’s less of a tech problem and more of a change management and human-centered design challenge.

What is your forecast for the application of artificial intelligence in medical diagnostics?

My forecast is one of cautious but profound optimism. Over the next five to ten years, I believe AI will become a standard, indispensable part of the diagnostic toolkit, much like the stethoscope or the MRI. We will move beyond just detection and classification to more predictive models that can forecast a patient’s response to a specific therapy based on their unique pathology, a true cornerstone of precision medicine. However, this future is not guaranteed. Its arrival depends entirely on our ability to solve the critical challenges of data diversity and seamless clinical integration. If we can successfully build the robust, equitable datasets and the user-friendly workflows needed, AI will fundamentally elevate the practice of medicine, empowering clinicians to make faster, more accurate, and more personalized decisions for every patient.