The human immune system operates as a phenomenally powerful and precise biological defense force, armed with an arsenal of cells and molecules capable of seeking out and annihilating a vast array of pathogens. Yet, this incredible power raises a profound and once-unanswered question: what prevents this potent internal army from turning its weapons against the very body it is designed to protect? The answer, which eluded scientists for the better part of a century, is not a passive absence of self-reactive soldiers but the active, constant diplomacy of a specialized cellular peacekeeping unit. These guardians work tirelessly behind the scenes to enforce a delicate truce, ensuring that our immune defenses target only genuine threats while maintaining peace within our own tissues, a process now understood as immunological self-tolerance.

A Century-Old Immunological Paradox

The quest to understand this internal peace treaty began over a century ago with the foundational work of Paul Ehrlich, a German physician widely regarded as the father of modern immunology. Having won a Nobel Prize for his research on antitoxins, Ehrlich was acutely aware of the immune system’s destructive capacity. This led him to formulate a concept he termed horror autotoxicus, or the “dread of self-poisoning,” to describe the body’s apparent inability to mount an immune attack against itself. His initial hypothesis was elegantly simple: the body must have a mechanism that prevents it from ever producing self-reactive immune cells or antibodies in the first place. This idea of a built-in safety check laid the crucial groundwork for the concept of self-tolerance, but it would ultimately be proven incomplete, paving the way for the discovery of a far more dynamic and sophisticated system of control that actively suppresses autoimmunity.

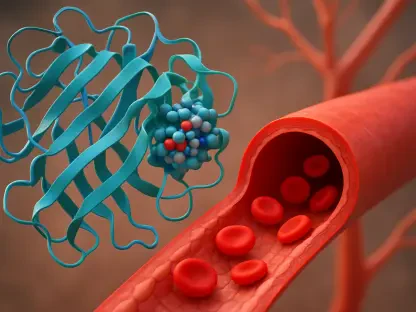

This active mechanism is embodied by a specialized class of immune cells known as regulatory T cells, or Tregs. These cells are the functional guardians that enforce the principle Ehrlich first identified, acting as the immune system’s dedicated mediators and suppressors. Their primary mission is to prevent harmful inflammation and rein in excessive immune reactions that could otherwise damage healthy tissue. This vital role extends to maintaining tolerance to the trillions of beneficial commensal microbes living in our gut, preventing allergic reactions to harmless environmental substances like dust and pollen, and, remarkably, protecting a developing fetus from being rejected by the mother’s immune system during pregnancy. Without the constant surveillance and suppressive action of Tregs, the immune system would indiscriminately attack pathogens and the body’s own cells alike, resulting in catastrophic, widespread autoimmune disease.

The Difficult Path to Scientific Validation

The journey to formally recognizing Tregs was anything but linear, marked by promising leads that culminated in major setbacks. Initial evidence for what were then called “suppressor T cells” emerged from studies in the late 1960s and early 1970s, sparking over a decade of intense research. A prominent theory emerged linking the identity of these cells to a genetic region named I-J. However, this line of inquiry led the entire field to a dead end. In the mid-1980s, significant advances in DNA sequencing technology enabled scientists to search for the proposed I-J genes, but the search came up empty. This critical failure discredited the entire suppressor T cell concept, and with a lack of reliable molecular markers or compelling clinical evidence, the scientific community largely abandoned and dismissed the idea for nearly a decade, casting a long shadow over the researchers who had championed it.

The field experienced a dramatic and definitive resurgence in 1995, thanks to the landmark research of Shimon Sakaguchi at the Tsukuba Life Science Center in Japan. His work provided the unequivocal validation that had been missing for decades, effectively rediscovering and rebranding the concept as regulatory T cells. Sakaguchi’s team identified a small subset of T cells, characterized by a surface marker called CD25, and demonstrated their indispensable role in maintaining self-tolerance. In a pivotal series of experiments, they showed that removing this specific cell population from mice invariably led to the development of severe, uncontrolled autoimmune diseases. Even more critically, they proved that re-administering these same cells to the afflicted animals could halt the progression of the disease. This provided the first concrete evidence that a distinct lineage of T cells actively and dynamically controls immune responses against the body’s own tissues, a foundational discovery recognized with the 2025 Nobel Prize.

Deciphering the Molecular Master Switch

Following Sakaguchi’s breakthrough, the scientific community raced to identify the molecular machinery that governs the development and function of Tregs. The discovery of the master regulator gene, FOXP3, was the result of several parallel lines of investigation converging. Researchers Fred Ramsdell and Mary Brunkow were studying a unique strain of mice that suffered from a fatal autoimmune syndrome when they traced the cause to a damaging mutation in a gene they named Foxp3. Their initial hypothesis was that the gene acted as a general brake on all T cells. However, a key insight emerged from a conversation between another Treg pioneer, Alexander Rudensky, and Fred Ramsdell. Rudensky proposed that FOXP3 was not a general inhibitor but rather the specific “missing link”—the master switch that exclusively defined Treg identity and function. This crucial connection unified the research, and soon after, the labs of Sakaguchi, Rudensky, and Ramsdell/Brunkow all published findings confirming that the Foxp3 gene encodes the essential molecular program that instructs a developing T cell to become a Treg.

The absolute importance of FOXP3 in humans was tragically but undeniably confirmed through the study of a rare and life-threatening condition known as IPEX syndrome, an X-linked immune deficiency. Infants born with mutations in the human FOXP3 gene are unable to produce functional Tregs. As a consequence, their immune systems unleash a relentless and systemic attack against their own organs and tissues, leading to severe, multi-organ autoimmunity that is fatal if left untreated. This devastating disease provided stark and definitive proof from human genetics that the FOXP3 master switch is non-negotiable for enforcing self-tolerance. It cemented the gene’s role as the central controller of immune regulation in humans, transforming a discovery made in laboratory mice into a cornerstone of clinical immunology and offering a clear molecular target for potential therapeutic intervention.

A New Frontier in Cellular Therapy

The foundational discoveries of Tregs and their master regulator, FOXP3, launched a new era in medicine focused on precisely manipulating these cellular guardians to treat a wide spectrum of diseases. The clinical challenges, however, are complex and often contradictory depending on the condition. For autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis or lupus, as well as in preventing the rejection of transplanted organs, the therapeutic goal is to enhance or supplement Treg function to calm an overactive immune system. Conversely, in the context of cancer, Tregs play a detrimental role by suppressing the immune system’s ability to recognize and destroy tumor cells, effectively shielding the cancer from attack. The challenge, therefore, is not to uniformly eliminate all Tregs—an act that would trigger devastating autoimmunity—but to develop sophisticated strategies that can selectively silence only the Tregs operating within the tumor microenvironment.

This nuanced understanding led to innovative therapeutic strategies currently being tested in clinical trials. One of the most promising approaches for organ transplantation involves engineering a patient’s own Tregs to become chimeric antigen receptor Tregs, or CAR-Tregs. These cells are specifically designed to recognize the foreign proteins of a donated organ, such as a kidney or liver, and selectively silence the recipient’s T cells that would otherwise cause organ rejection. This technology holds the potential to induce a state of graft-specific tolerance, potentially freeing patients from a lifetime of generalized immunosuppressant drugs and their associated side effects. The journey from Ehrlich’s century-old paradox to the first-in-human clinical trials of engineered Tregs represents a remarkable progression of scientific thought. This evolution, built on decades of perseverance, culminated in a Nobel-winning understanding of our body’s internal guardians and paved the way for a new generation of life-saving therapies.