Within the intricate ecosystem of a tumor, cancer cells are far from acting alone; they are surrounded by a complex network of supporting cells that form the tumor microenvironment. Among these collaborators, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) have emerged as particularly influential players. Once dismissed as simple structural elements, these cells are now recognized as dynamic and powerful regulators of cancer progression, actively shaping a tumor’s growth, its ability to spread, and its response to medical treatment. Their role, however, is deeply complex and often contradictory. CAFs represent a true double-edged sword, possessing the capacity to both fuel the disease and, under certain circumstances, potentially restrain it. This duality presents one of the most significant challenges in modern oncology, while also opening a new frontier of therapeutic possibilities that could redefine how we combat cancer. Understanding this complex cellular actor is paramount to developing more effective and personalized treatments for patients.

The Architects of the Tumor Microenvironment

The Diverse Origins of a Complex Cell

The profound complexity of cancer-associated fibroblasts begins with their varied origins, which prevent them from being categorized as a single, uniform cell type. Instead, they constitute a heterogeneous collection of cell populations derived from several distinct sources. A primary pathway involves the activation of resident fibroblasts already present in the host tissue; these cells are switched into a pro-tumorigenic state by continuous signaling from nearby cancer cells. Another significant portion of the CAF population originates from bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells, which are recruited to the tumor site where they differentiate into fibroblasts. Furthermore, CAFs can arise through a process known as epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), in which cancer cells or other epithelial cells undergo a transformation, shedding their original characteristics to acquire a fibroblast-like identity. This mosaic of cellular origins is the fundamental driver behind the remarkable functional diversity observed among different CAF populations within the tumor microenvironment.

This inherent heterogeneity extends far beyond their origins, directly influencing their functional roles and creating a landscape of cellular diversity that complicates therapeutic strategies. The specific source of a CAF can dictate its behavior and its interactions within the tumor. For instance, a CAF derived from a local resident fibroblast might secrete a different profile of signaling molecules compared to one that originated from a cancer cell through EMT. This functional variability means that while some CAFs are actively promoting tumor growth and invasion, others within the same tumor might be playing a different, or even opposing, role. This complex reality underscores the challenge for researchers and clinicians: a therapeutic approach designed to target a specific CAF function might be ineffective against other subpopulations or, worse, could inadvertently disrupt a delicate balance, highlighting the critical need for a deeper understanding of this cellular diversity.

Building the Tumor’s Malignant Scaffolding

One of the most well-documented and detrimental roles of CAFs is their function as the master architects of the tumor’s physical structure. They actively and extensively remodel the extracellular matrix (ECM)—the intricate web of proteins and molecules that provides structural support to tissues. Pro-tumorigenic CAFs secrete a variety of enzymes that systematically break down the existing, organized matrix. In its place, they deposit a new, dense, and rigid scaffold composed of proteins like collagen. This remodeled ECM provides a robust physical framework that not only supports the growing tumor mass but also alters the mechanical properties of the tissue, making it stiffer. This increased rigidity can, in turn, promote malignant cell behaviors, creating a feedback loop where the altered environment further encourages tumor progression and survival, turning the surrounding tissue into a supportive niche for the cancer.

Beyond simply providing a supportive structure, the remodeled ECM created by CAFs plays a direct and critical role in cancer metastasis. The disorganized and stiff matrix is not a uniform barrier; instead, it contains aligned fibers that function as veritable “highways” for migrating cancer cells. These pathways guide invasive tumor cells out of the primary tumor and into the surrounding tissue, facilitating their entry into the bloodstream or lymphatic system. By engineering these routes of escape, CAFs are not just passive supporters but active participants in the metastatic cascade, the process responsible for the vast majority of cancer-related deaths. This architectural function underscores their significance as therapeutic targets, as disrupting their ability to build these invasive pathways could be a powerful strategy for preventing the spread of cancer to distant organs.

A Complicated and Contradictory Alliance

The Dangerous Crosstalk Between CAFs and Cancer Cells

The powerful influence of CAFs is largely exerted through a continuous, bidirectional communication with tumor cells and other components of the microenvironment. This intricate crosstalk operates as a self-reinforcing feedback loop mediated by a vast array of signaling molecules, including cytokines, chemokines, and potent growth factors like transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β). Tumor cells initiate this dialogue by releasing signals that activate nearby fibroblasts, transforming them into the pro-tumorigenic CAF phenotype. Once activated, these CAFs respond by secreting their own cocktail of factors that profoundly alter the behavior of the cancer cells. This reciprocal exchange enhances the invasive and migratory capabilities of the tumor, fosters an immunosuppressive environment, and ultimately drives the co-evolution of both cell types toward a more aggressive and resilient state.

The consequences of this symbiotic relationship are far-reaching, extending beyond simple growth promotion to cultivate a holistically malignant phenotype. The persistent signaling between CAFs and cancer cells establishes a microenvironment that is not only conducive to proliferation but is also actively hostile to the body’s immune defenses. CAFs secrete molecules that can dampen the activity of immune cells and remodel the ECM to physically block their access to the tumor. This creation of an “immunosuppressive shield” is a critical aspect of their pro-tumorigenic function. This complex interplay underscores the necessity of developing therapeutic interventions that can disrupt this symbiotic relationship, as targeting only the cancer cells while leaving the supportive CAFs intact may prove insufficient for achieving lasting therapeutic success.

An Unexpected Ally in the Fight?

The “double-edged sword” nature of CAFs is most clearly demonstrated by the growing body of evidence suggesting that not all of these cells are detrimental. Scientific research has successfully identified distinct subpopulations of CAFs that appear to exhibit anti-tumor properties, complicating the narrative of CAFs as purely villainous actors. These potentially beneficial CAFs may function by secreting signals that attract, rather than repel, anti-cancer immune cells, helping to mount an effective immune response against the tumor. In other contexts, certain CAF subtypes might contribute to the formation of a more organized, capsule-like matrix that physically contains the tumor, thereby limiting its ability to invade surrounding tissues. This functional dichotomy means that the overall effect of the CAF population within a tumor is a delicate balance between pro-tumorigenic and anti-tumorigenic forces.

This functional plasticity presents a formidable challenge for the development of new cancer therapies. A broad-spectrum therapeutic strategy designed to eliminate all CAFs indiscriminately carries a significant risk: it could inadvertently destroy these beneficial populations along with the harmful ones. Such an approach could disrupt the delicate equilibrium within the tumor microenvironment, potentially tilting the balance in favor of tumor progression and leading to an even more aggressive disease phenotype. This realization has shifted the therapeutic goal away from simple eradication toward a more nuanced strategy of selective targeting or “reprogramming.” The challenge now is to identify reliable biomarkers that can distinguish between helpful and harmful CAF subtypes, allowing for precision therapies that can selectively neutralize the pro-tumorigenic cells while sparing, or even enhancing, the anti-tumorigenic ones.

A Formidable Barrier to Cancer Treatment

Shielding the Enemy from Traditional Therapies

One of the most clinically significant challenges posed by cancer-associated fibroblasts is their central role in mediating resistance to conventional cancer therapies like chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Tumors that are heavily populated with CAFs frequently demonstrate a markedly reduced sensitivity to these treatments, leading to poor patient outcomes. A key mechanism behind this resistance is physical. CAFs construct a dense and highly cross-linked extracellular matrix that acts as a formidable physical barrier. This dense meshwork can significantly impede the penetration of chemotherapeutic drugs, preventing them from reaching the cancer cells in sufficient concentrations to be effective. For radiotherapy, the altered matrix can create a hypoxic (low-oxygen) environment, which is known to make cancer cells more resistant to the damaging effects of radiation.

In addition to creating a physical shield, CAFs also confer biochemical resistance through complex paracrine signaling networks. They secrete a wide range of survival factors and growth factors that directly counteract the cytotoxic effects of cancer treatments. When cancer cells are exposed to chemotherapy, which is designed to induce cell death, nearby CAFs can release signals that activate pro-survival pathways within the tumor cells, effectively overriding the therapeutic command to die. This protective signaling allows cancer cells to withstand the therapeutic assault, continue to proliferate, and ultimately drive tumor relapse. Understanding the specific molecular mechanisms behind this CAF-induced resistance is therefore a critical priority for improving the efficacy of existing treatment regimens and developing novel strategies to overcome treatment failure in patients with CAF-rich tumors.

Sabotaging the Immune Response

The influence of cancer-associated fibroblasts extends into the realm of modern medicine, where they act as major saboteurs of groundbreaking immunotherapies, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors. While these therapies have revolutionized cancer treatment by “reawakening” the immune system to fight tumors, their effectiveness can be severely limited in the presence of certain CAF subtypes. These immunosuppressive CAFs are particularly adept at creating a hostile microenvironment that neutralizes the anti-tumor immune response. They achieve this, in part, by remodeling the ECM into a dense, fortress-like structure that physically blocks the infiltration of cancer-fighting immune cells, like cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. Even if T-cells manage to breach this outer defense, the path to the tumor core is often obstructed, preventing them from reaching and destroying their targets.

Beyond constructing physical barriers, immunosuppressive CAFs also engage in chemical warfare against the immune system. They secrete a variety of factors, including cytokines like TGF-β and chemokines, that directly dampen the activity and function of effector immune cells. These molecules can inhibit the proliferation of T-cells, induce their exhaustion, and promote the accumulation of regulatory T-cells, which further suppress the anti-tumor response. This multifaceted sabotage creates a potent immunosuppressive shield around the tumor, rendering it invisible or inaccessible to the body’s natural defenses and making it resistant to even the most advanced immunotherapies. Consequently, developing strategies to specifically target and neutralize these immunosuppressive CAF populations has become a key focus of research aimed at unlocking the full potential of immunotherapy for a broader range of patients.

Targeting CAFs: A New Frontier in Oncology

Developing Smarter and More Selective Strategies

The profound and multifaceted influence of CAFs on nearly every aspect of tumor biology has solidified their status as a high-priority target for the next generation of cancer therapies. Recognizing the risks of broad elimination, the focus of current research has shifted toward more sophisticated and selective strategies. The goal is no longer to simply destroy all CAFs but to strategically manipulate their behavior. One promising approach involves the development of agents that can inhibit the specific signaling pathways responsible for activating fibroblasts or that block the downstream pro-tumorigenic functions of already activated CAFs. Another innovative avenue explores the use of genetically engineered therapeutics, such as CAR-T cells designed to recognize specific markers on the surface of pro-tumorigenic CAFs, allowing for their precise elimination while sparing other cells.

Perhaps the most sophisticated strategy being pursued is the concept of “reprogramming” harmful CAFs. This approach aims to convert pro-tumorigenic fibroblasts into a quiescent or even an anti-tumorigenic state, effectively turning a foe into an ally. For instance, researchers are investigating drugs that can alter the gene expression patterns in CAFs, compelling them to stop secreting immunosuppressive factors and instead produce molecules that support an anti-tumor immune response. By remodeling the remodelers, these therapies could fundamentally alter the tumor microenvironment, making it less hospitable for cancer cells and more susceptible to other treatments, particularly immunotherapy. This push toward smarter, more nuanced interventions represents a significant evolution in cancer treatment, moving from brute-force cytotoxicity to precision-guided manipulation of the tumor ecosystem.

The Future is Personalized and Precise

The significant heterogeneity within the CAF population has made it clear that a one-size-fits-all therapeutic approach is destined to fail. The path forward in oncology lies in developing personalized treatment strategies that are tailored to the specific CAF subpopulation profile present in an individual patient’s tumor. The identification of reliable biomarkers that can distinguish between different CAF subtypes is a crucial step in this direction. Such biomarkers could be used to stratify patients, predicting who is most likely to respond to a particular anti-CAF therapy and guiding the selection of the most effective treatment course. This would allow clinicians to target the specific CAF-cancer interactions driving the disease in each patient, maximizing efficacy while minimizing potential side effects.

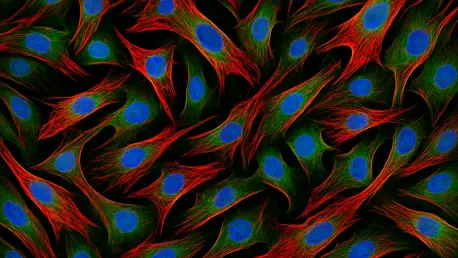

This pursuit of personalized medicine has been dramatically accelerated by the advent of powerful new technologies. Advanced techniques such as single-cell RNA sequencing and high-resolution in vivo imaging are providing an unprecedented level of detail into the functional states and spatial organization of different CAF subpopulations within the living tumor microenvironment. These tools are indispensable for dissecting the complex cellular interactions in real-time, revealing the specific conversations between CAFs and cancer cells. The insights gained from this research had already begun to translate fundamental biological knowledge into clinically meaningful interventions. Ultimately, this precision-focused approach promised not only to improve the efficacy of cancer treatments but also to usher in a new era where therapy is as unique as the patient receiving it.