As a biopharma expert deeply invested in the intersection of technology and healthcare delivery, I’ve spent my career focused on innovation in research and development. My latest work, however, has shifted focus to a more fundamental problem: the stubborn gaps in who gets to benefit from modern medicine. Our recent study analyzed over 14,000 patient records and uncovered a troubling, yet revealing, paradox in genetic medicine, highlighting that the biggest barriers to care aren’t what we’ve long assumed. We’re exploring the systemic hurdles that prevent equitable access to genetic services, the crucial role of clear clinical guidelines in leveling the playing field, and tangible solutions—like rethinking clinic workflows and leveraging virtual care—to ensure that the promise of precision medicine reaches every community.

Your study found Black and low-income patients are under-represented in genetics clinics, yet more likely to accept testing and get actionable results once evaluated. Could you elaborate on what this surprising reversal tells us about the true barriers and perhaps share an anecdote that illustrates this phenomenon?

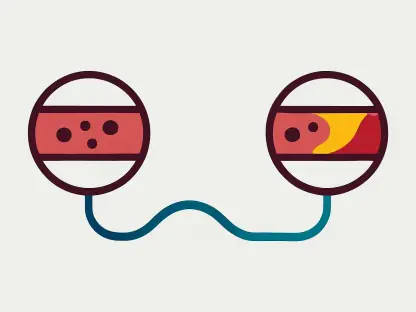

This reversal is one of the most powerful findings, as it completely upends the long-held and damaging narrative of “patient hesitancy.” For years, the assumption has been that certain communities are wary of genetic testing, but our data paints a very different picture. We saw representation rates for Black patients and those from disadvantaged neighborhoods at half or even less than their wealthier, White counterparts. But the moment they were in the room with a specialist, the story changed. Not only were they more likely to have testing ordered, but those from lower-income areas were also more likely to receive a definitive, actionable result. This tells us the problem isn’t a lack of interest; it’s a lack of invitation. Imagine a patient who has been watching family members struggle with an illness for years, carrying that quiet worry. When a provider finally connects the dots and offers them a clear path to an answer through a genetic test, the response isn’t hesitation—it’s relief and a profound desire for knowledge that could protect them and their children. The barrier was never their willingness; it was getting through the door in the first place.

The research pinpoints the referral stage as the “real bottleneck.” Could you walk us through the specific systemic barriers in a typical primary care setting—like clinic hours or referral patterns—that prevent patients who could benefit most from ever being considered for genetic services?

The primary care setting is where the trickle of referrals should start, but it’s often where the pipeline gets clogged. Think about the reality of a busy clinic. A primary care physician is managing multiple chronic conditions in a 15-minute slot. They may lack specialized, up-to-the-minute knowledge about which specific family histories warrant a genetics referral. Then there are the logistical hurdles. A genetics clinic might only operate during standard business hours, which is an impossible barrier for a patient working an hourly job without paid time off. The referral process itself can be a maze of paperwork and phone calls, and if a patient’s insurance isn’t straightforward, it’s another layer of complexity. These aren’t malicious barriers; they are systemic frictions that accumulate. Over time, these small obstacles create ingrained referral patterns where providers, consciously or not, are more likely to refer patients who they perceive have the time, resources, and insurance coverage to navigate the system, inadvertently leaving behind those who might need the services most.

The study contrasts the success in cancer genetics, where guidelines have reduced disparities, with other areas. For adult genetic conditions without clear guidelines, how does this ambiguity specifically impact a doctor’s decision to refer a patient and an insurer’s willingness to cover the associated costs?

The difference is like night and day. In cancer genetics, there has been a massive, concerted effort to create clear, evidence-based national guidelines. A doctor can see a patient with a specific type of breast cancer at a certain age, check a box on a form, and the referral for BRCA testing is considered standard of care. Insurers have a clear justification to cover it, and the process is streamlined. This has been instrumental in reducing racial disparities in that field. Now, contrast that with other adult genetic conditions, like certain inherited cardiac or kidney diseases. Without those clear-cut guidelines, the decision to refer becomes a judgment call fraught with uncertainty. The provider has to spend extra time building a case for the referral, and they know the insurer might push back. For the patient, this ambiguity can translate into a fear of surprise medical bills. This hesitation on both sides—the doctor’s and the patient’s—means that a potentially life-saving diagnosis is missed, not because the science isn’t there, but because the system hasn’t created a clear, sanctioned pathway to access it.

You propose several promising interventions, such as embedding genetic counselors in primary care. Can you describe the step-by-step process of how that solution would work in a real-world clinic to successfully close the referral gap and connect an underserved patient with necessary care?

Embedding a genetic counselor is about removing friction and building trust right at the point of care. Imagine a patient is at their annual check-up, and as the doctor reviews their family history in the electronic health record, a flag pops up suggesting a potential hereditary risk. In the old model, this would trigger a cumbersome referral to a different facility, maybe weeks or months away. In the embedded model, the doctor can say, “You know, your family history has some red flags I’d like to explore. We have a genetics expert, Sarah, right here in our clinic. Do you have a few minutes to chat with her after our appointment?” This “warm handoff” is transformative. The patient can meet the counselor immediately, putting a face to the specialty and demystifying the process. The counselor can conduct an initial assessment, answer questions on the spot, and even schedule a follow-up via telehealth for a more in-depth discussion. This single change bypasses the referral bottleneck, eliminates travel and scheduling barriers, and provides immediate, trusted expertise, connecting the patient to care before they can get lost in the system.

What is your forecast for equitable access to genetic testing?

My forecast is one of cautious optimism, but it hinges entirely on our willingness to redesign the systems of delivery, not just advance the technology. The science of genomics is moving at an incredible pace, but its benefits will remain inequitable if we don’t fix the pathways to access. The future I see—and the one we must build—involves a multi-pronged approach. We’ll see electronic health records become smarter, with automated flags that don’t just prompt but actively assist in the referral process. We will see care models shift, with more genetic counselors and specialists embedded in community clinics and accessible through virtual platforms, meeting patients where they are. However, none of this will be enough without policy changes that create clear guidelines and mandate coverage for a wider range of conditions. The urgency is immense. As genetic insights become foundational to routine care, failing to build these equitable systems means we risk creating a new generation of medical disparities, where precision medicine benefits only a privileged few. True progress means ensuring that a person’s zip code or skin color no longer determines their access to their own genetic blueprint.