We are joined by biopharma expert Ivan Kairatov to discuss a groundbreaking discovery that redefines our understanding of IDH-mutant glioma, the most common malignant brain tumor in young adults. This conversation explores how this cancer begins not as a visible mass, but as a stealthy infiltration of mutated cells in seemingly normal brain tissue. We will delve into the cutting-edge technology that pinpointed these “cells of origin,” the development of a novel animal model that confirms the theory, and why this finding demands a complete overhaul of diagnostic and treatment strategies. Ultimately, this research, born from a surgeon’s persistent question, illuminates a new path toward early detection and preventing recurrence.

The discovery that IDH-mutant gliomas start in normal-looking brain tissue is a major shift. Could you explain how these “cells of origin” spread before a tumor mass forms and what challenges this presents for conventional treatments that are focused only on surgically removing visible tumors?

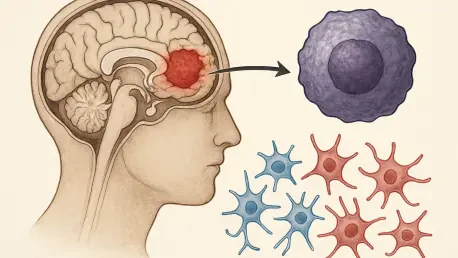

This is truly a paradigm shift. What the research from KAIST and Severance Hospital has shown is that the disease process begins long before we can see anything on an MRI. It starts with the initial IDH mutation occurring in a single cell, which then begins to divide and spread out within the cerebral cortex. These cells look and act, for the most part, like normal brain tissue. They are a hidden enemy, integrating themselves into the brain’s architecture. The challenge this creates for a surgeon is immense. When they go to resect a tumor, they are removing the large, visible mass that has accumulated additional mutations, but they are leaving behind this entire network of precursor cells in tissue that appears perfectly healthy to the naked eye. This is precisely why the recurrence rate is so high; we’ve been cutting out the tip of the iceberg while the vast, unseen majority remains, ready to grow back.

You used a cutting-edge technique, spatial transcriptomics, to identify the specific origin cells. Could you walk us through how this technology works and explain why pinpointing Glial Progenitor Cells as the source is such a critical breakthrough for understanding this specific type of glioma?

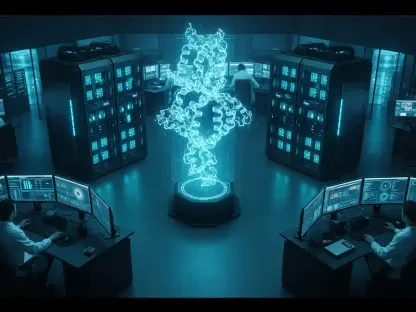

Spatial transcriptomics is like giving scientists a high-definition GPS for gene activity inside tissue. Instead of just grinding up a tissue sample and getting an average reading of all the genes being expressed, this technology allows us to see which specific genes are turned on or off in each individual cell, while keeping that cell’s exact location on the map. The research team applied this to the tumor and the surrounding “normal” brain tissue. It allowed them to find these scattered cells harboring the IDH mutation and then ask, “What kind of cell are you?” The data revealed their identity as Glial Progenitor Cells, or GPCs. Pinpointing GPCs is a monumental breakthrough because it gives us a specific target. We now know the enemy isn’t just a generic “cancer cell,” but a very particular type of progenitor cell that we can now study, track, and hopefully, eliminate.

Successfully creating a brain tumor in an animal model by introducing a specific mutation is a significant step. How does this mouse model confirm your theory about the tumor’s origin, and what specific pathways does it reveal for developing RNA-based drugs that target these early cells?

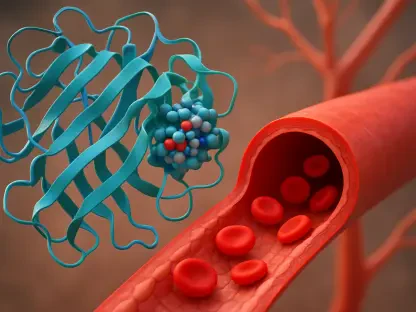

This was the elegant, final piece of the puzzle. It’s one thing to find these mutated cells in patient tissue, but it’s another to prove they are the cause. The researchers took the exact “driver mutation” found in patients and, using precise genetic tools, introduced it only into the GPCs of mice. When those mice went on to develop tumors that mirrored the human disease, it provided definitive proof that GPCs are indeed the cell of origin. This animal model is now an invaluable platform. It’s a living system where we can test new therapies aimed at the very first step of tumor formation. This is particularly exciting for developing RNA-based drugs, like those being pursued by Sovagen. We can design therapies that specifically target the mutated IDH gene within these GPCs, potentially correcting their function or eliminating them before they ever have a chance to evolve into a full-blown, refractory tumor.

We now understand that IDH-mutant gliomas and IDH wildtype glioblastomas have entirely different origins. Could you elaborate on these different developmental pathways and explain why this finding underscores the need for highly specific, subtype-focused diagnostic tools and recurrence-prevention strategies?

This finding really drives home the point that “brain cancer” is not a single disease. In 2018, the same team showed that IDH wildtype glioblastoma, a very aggressive tumor, originates from neural stem cells in a deep part of the brain called the subventricular zone. Now, they’ve proven that IDH-mutant glioma, which affects a younger population, starts from completely different cells—GPCs—in a different location, the cerebral cortex. These are fundamentally different biological paths. This distinction is critical because it means a one-size-fits-all approach is doomed to fail. We need diagnostic tools that can not only identify the tumor subtype but also potentially detect its unique cellular origin. This will allow us to develop tailored strategies for preventing recurrence, targeting the specific reservoir of origin cells unique to each patient’s cancer.

The motivation for this work came from a surgeon’s clinical question about a tumor’s true origin. Could you describe how this partnership between basic scientists and neurosurgeons works in practice and what specific steps are needed to translate this discovery into new diagnostic tools for patients?

This is a beautiful example of bench-to-bedside-and-back-again science. It began with Dr. Jung Won Park, a neurosurgeon, facing the frustration of treating patients whose tumors kept returning despite successful surgery. He carried that clinical question—”Where does this tumor really begin?”—from the operating room to the laboratory at KAIST. This synergy is powerful; the surgeons provide the patient tissues and the critical, real-world questions, while the basic scientists at KAIST provide the world-class technology and expertise to answer them. The next step in translation is to develop technologies that can “see” these early mutant cells. This could involve ultra-sensitive imaging techniques or perhaps liquid biopsies that can detect the genetic fingerprints of these GPCs in cerebrospinal fluid or blood. The goal is to move detection from the point where a mass is visible to the much earlier stage where we are only dealing with these scattered, originating cells.

What is your forecast for the early diagnosis and treatment of IDH-mutant glioma over the next decade?

Over the next decade, I forecast a profound shift from a reactive to a proactive paradigm. Instead of waiting for a visible tumor to appear on a scan, we will likely see the development of surveillance tools that can detect the signature of these mutated Glial Progenitor Cells in high-risk individuals. Treatment will move away from a primary focus on debulking surgery and toward innovative molecular therapies, like the RNA-based drugs in development, designed to specifically target and neutralize these origin cells across the brain. The ultimate goal will be to suppress the evolution of the tumor entirely, transforming what is now a refractory cancer into a manageable, perhaps even preventable, condition. This research has opened the door to a future where we treat the seeds of the cancer, not just the tree.