In the relentless search for effective Alzheimer’s treatments, where many promising paths have led to dead ends, researchers are now turning their attention to a rather unlikely source: an enzyme responsible for producing the gas that gives rotten eggs their infamous smell. This enzyme, Cystathionine γ-lyase or CSE, is emerging as a critical player in brain health and memory. The latest research, moving beyond previous studies, isolates CSE to reveal its standalone importance in cognitive function. Today, we’ll delve into how the absence of this single protein can trigger a cascade of damage mirroring Alzheimer’s disease, from progressive memory loss observed in mice to the breakdown of the brain’s crucial defenses. We will explore the delicate paradox of its gaseous product, hydrogen sulfide—a neuroprotector that is also a toxin—and discuss the innovative strategies being considered to harness its benefits safely, potentially offering a new therapeutic avenue for the more than 6 million Americans living with this devastating disease.

The Barnes maze experiment revealed a stark difference in spatial memory between normal mice and those lacking CSE at six months. Could you walk us through the specifics of this decline and explain how this progressive memory loss directly mirrors symptoms seen in human Alzheimer’s patients?

Absolutely. The Barnes maze is a fascinating and effective tool for assessing spatial memory. Imagine a circular platform with several holes around the edge, only one of which leads to a safe, dark shelter. A bright, unpleasant light is used to motivate the mice to find this escape route. In the study, at two months of age, both the normal mice and the mice genetically engineered to lack the CSE enzyme were equally adept. They learned the task and consistently found the shelter within the three-minute window. The really telling moment, however, came four months later. At six months old, the normal mice still remembered the task perfectly. But the mice without CSE were lost. They couldn’t find the escape route, wandering aimlessly. This isn’t just a simple failure of memory; it’s a “progressive onset” of decline, as the researchers termed it. This gradual worsening over time is a chilling echo of what happens in human Alzheimer’s patients, whose memory and cognitive abilities deteriorate not overnight, but over months and years. Seeing it unfold so clearly in this controlled experiment, attributable solely to the loss of CSE, was a powerful confirmation of the enzyme’s critical role.

Your team observed significant physiological damage, including a compromised blood-brain barrier and impaired neurogenesis in the hippocampus. Can you detail the step-by-step process you used to identify these issues and elaborate on the connection between a faulty CSE enzyme and these specific cellular breakdowns?

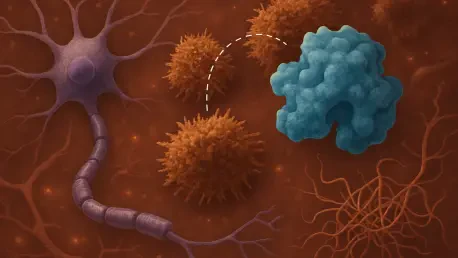

The investigation into the physical damage was a multi-layered process, almost like neurological detective work. First, the team focused on the hippocampus, the brain’s memory and learning hub. They knew that disruptions in the formation of new neurons there, a process called neurogenesis, are a classic hallmark of neurodegenerative disease. Using a series of biochemical and analytical techniques, they compared the brains of mice with and without CSE. The results were stark: the proteins essential for neurogenesis were either expressed far less often or were completely absent in the mice lacking CSE. This told them the factory for new brain cells was essentially shutting down. To get an even closer look, they brought in the heavy artillery: high-powered electron microscopes. When they examined the brains of the CSE-lacking mice, they saw something alarming—big breaks and gaps in the blood vessels. This was clear evidence of a damaged blood-brain barrier, the critical shield that protects the brain from harmful substances. Not only was the neuron factory broken, but the city walls were crumbling. Furthermore, they observed that the few new neurons that did form had a terrible time migrating to the hippocampus where they were needed. The connection to CSE is profound; its absence appears to set off a domino effect, leading to oxidative stress and DNA damage that ultimately compromises the brain’s structure and function at multiple, critical levels.

Hydrogen sulfide is described as both a neuroprotector and a toxin, making direct therapy challenging. How does this paradox shape your team’s strategy, and what potential mechanisms are you exploring to safely boost CSE expression and maintain optimal, non-toxic gas levels in the brain?

This paradox is the central challenge, and it completely shapes the therapeutic strategy. You can’t just pump hydrogen sulfide gas into the brain; at high doses, it’s toxic and would do more harm than good. It’s like a life-giving substance that becomes a poison if you have too much of it. The key is maintaining the infinitesimally small, delicate balance that exists naturally in healthy neurons. So, the strategy isn’t to administer the gas directly. Instead, the focus is on the source: the CSE enzyme itself. The goal is to develop drugs or therapies that can boost the body’s own expression of CSE. By targeting the enzyme, we could theoretically encourage brain cells to produce their own hydrogen sulfide at precisely the right, beneficial, non-toxic levels. This is a far more elegant and safer approach. We are essentially trying to fix the factory rather than just flooding the market with its product. The mechanisms for this could involve small molecules that enhance the gene’s expression or stabilize the protein, ensuring it functions correctly and produces just enough of this crucial gas to protect neurons without reaching toxic concentrations.

This study distinguished itself from previous work by isolating CSE as a standalone factor in cognitive decline. What key element of your experimental design allowed you to make this crucial distinction, and what was the most surprising anecdote or finding that emerged during your analysis?

The crucial element of the experimental design was its elegant simplicity. Previous research, while incredibly valuable, often studied CSE in mice that were already genetically engineered with other mutations known to cause diseases like Huntington’s or Alzheimer’s. This made it difficult to tell if the problems observed were due to the loss of CSE, the other mutations, or a combination of both. In this new work, the scientists used a line of mice from a 2008 study whose only genetic alteration was the lack of the CSE protein. They had no other built-in neurodegenerative conditions. By doing this, the researchers created a clean slate. Any cognitive or physiological problems that emerged could be attributed directly and solely to the absence of CSE. This is what allowed them to state confidently that CSE alone is a “major player” in cognitive function. For me, the most surprising finding wasn’t just one thing, but the sheer scope of the damage. To think that removing a single enzyme could lead to memory loss, a leaky blood-brain barrier, and a failure to create and deploy new neurons is staggering. It underscores how interconnected our biological systems are and how a single point of failure can have such devastating, system-wide consequences that so closely mimic a complex disease like Alzheimer’s.

What is your forecast for CSE-targeting therapies in Alzheimer’s treatment?

My forecast is one of cautious but significant optimism. We are still in the early stages, but this research opens up a genuinely new avenue for treatment, which is incredibly valuable in a field that has seen many disappointments. To date, we have no cures for Alzheimer’s and very few treatments that can consistently slow its progression. The idea of harnessing an internal, natural protective mechanism by boosting the CSE enzyme is a powerful one. It moves away from just clearing plaques or tangles and toward promoting fundamental brain cell health and resilience. The path forward will involve developing drugs that can safely and effectively increase CSE expression in the human brain. This will be challenging, but the potential benefit is immense. I believe that within the next decade, we could see the first CSE-targeting therapies entering clinical trials, offering a novel strategy to help keep neurons healthy and potentially slow the devastating march of this disease. It represents a new and promising front in a very difficult fight.