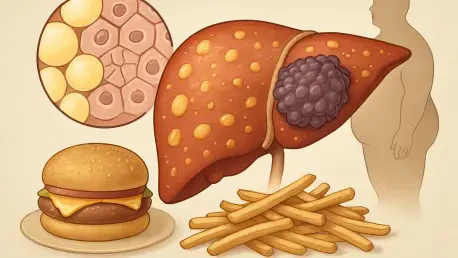

Beyond the familiar warnings about calories and cholesterol, a high-fat diet may be silently orchestrating a dangerous coup within the liver, transforming loyal, hardworking cells into precursors for malignant tumors. A landmark study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology provides a detailed molecular road map of this process, revealing for the first time how chronic dietary stress fundamentally rewires the liver’s cellular identity. Published in the journal Cell, this research moves beyond correlation to establish a causal chain of events, explaining how what is on the dinner plate can directly set the stage for one of the deadliest forms of cancer.

The work uncovers a critical, yet perilous, survival strategy employed by the body. Faced with an onslaught of fat, the liver’s primary cells, known as hepatocytes, begin a startling transformation. They shed their specialized, mature functions and revert to a more primitive, resilient state, similar to that of a stem cell. This change allows them to survive the toxic environment, but it comes with a devastating trade-off. By turning back their developmental clock, these cells also activate genetic pathways that make them highly susceptible to becoming cancerous, creating a cellular environment primed for disease.

Beyond Weight Gain How Your Diet Could Be Rewiring Your Cells for Disease

The central finding of the study is that a high-fat diet triggers a process of cellular reversion, or dedifferentiation, in the liver. This is not simply damage; it is a calculated reprogramming. Mature hepatocytes, which are normally dedicated to complex metabolic tasks like filtering blood and producing bile, begin to shut down these essential functions. Instead, they activate genes associated with proliferation and self-preservation, essentially prioritizing their own survival over the health of the organ and the organism as a whole. This shift represents a fundamental change in the cell’s purpose and identity.

This reversion is a double-edged sword. In the short term, it serves as a powerful adaptive mechanism. The liver is under siege from fat accumulation and inflammation, a condition known as steatotic liver disease. By becoming less specialized and more robust, the cells can better withstand this hostile environment. However, this survivalist state is inherently unstable. The very same genetic programs that help the cells survive also dismantle the natural safeguards that prevent uncontrolled growth, leaving them vulnerable to the mutations that drive cancer.

The Hidden Epidemic Connecting Modern Diets to Liver Health

To uncover these intricate cellular changes, the research team, led by a collaborative group of senior authors, employed a sophisticated approach. They fed mice a high-fat diet and used a powerful technique called single-cell RNA-sequencing to monitor gene activity within individual liver cells over time. This high-resolution analysis allowed them to watch as the liver progressed from a state of simple fat accumulation to inflammation, scarring (cirrhosis), and eventually, the formation of tumors. The data painted a clear and alarming picture of a step-by-step transformation.

The results illuminated a stark cellular trade-off. As the disease progressed, genes responsible for normal liver function were systematically switched off. The production of crucial metabolic enzymes and vital proteins plummeted. In their place, a suite of pro-survival genes was activated, including those that block programmed cell death (apoptosis) and encourage cell division. According to the study’s authors, this represents a shift toward a “selfish” cellular state, where the collective function of the tissue is sacrificed for the benefit of its individual components.

Unpacking the Science The Livers Dangerous Survival Strategy

This reversion process effectively lays the groundwork for cancer. The dedifferentiated hepatocytes, having shed their mature identity, have already completed several of the preliminary steps required for malignant transformation. They exist in a hyper-proliferative, pre-cancerous state, poised for a full-blown malignancy. The study suggests that these cells are not yet cancerous, but they have a significant head start. A single cancer-causing mutation, which might otherwise be harmless in a healthy cell, can rapidly push one of these “primed” cells toward forming a tumor.

This disturbing progression was not a rare occurrence in the laboratory model; it was a near certainty. The researchers observed that almost all the mice kept on the high-fat diet ultimately developed liver cancer. This consistent outcome underscores the powerful and direct link between the metabolic stress induced by the diet and the initiation of cancer. The liver’s desperate attempt to protect itself from one threat—fatty liver disease—directly creates a vulnerability to another, far more lethal one.

From the Lab to the Clinic Validating the Findings in Humans

While these findings in animal models are compelling, their true significance lies in their relevance to human health. The researchers extended their analysis to human liver tissue samples from patients at various stages of steatotic liver disease. They discovered a remarkably similar genetic signature. As the disease advanced in humans, the expression of genes associated with mature liver function declined, while the expression of the immature, pro-survival genes increased, mirroring the process observed in mice.

This shared genetic signature proved to be more than just a biological curiosity; it was a powerful predictor of patient outcomes. An analysis of tumor data revealed that patients whose cancers showed a stronger signature of this cellular reversion—that is, higher expression of pro-survival genes and lower expression of mature liver genes—had significantly shorter survival times. This direct correlation confirms that the cellular reprogramming is not just a side effect of the disease but a key driver of its aggression in humans.

A New Frontier in Prevention Targeting the Cellular Reprogramming

A critical contribution of this research is the identification of the molecular “master controls” that orchestrate this dangerous reprogramming. The team pinpointed several transcription factors—proteins that control which genes are turned on or off—that appear to drive the reversion process. One key player is SOX4, a factor typically active only during fetal development. Its reactivation in adult liver cells under metabolic stress seems to be a crucial step in stripping them of their mature identity. These factors represent promising new targets for therapies designed to halt or even reverse the process.

This new understanding opens a crucial window for intervention. The researchers estimate that while the entire progression from dietary stress to cancer may take only a year in mice, it likely unfolds over a much longer period in humans, possibly around 20 years. This timeline provides a significant opportunity to act. Future research will explore whether these cellular changes are reversible. Scientists plan to investigate if a return to a healthy diet or the use of modern weight-loss medications can coax the reverted hepatocytes back to their mature, functional state, thereby reducing cancer risk. The study provided a profound biological insight, linking a common lifestyle factor to a deadly disease with unprecedented clarity. The work not only explained how high-fat diets promote liver cancer but also identified specific molecular targets that could lead to a new generation of preventive therapies. This knowledge has shifted the focus from merely managing symptoms to potentially disrupting the cancer-causing process at its earliest stages.