Biopharma expert Ivan Kairatov joins us to discuss a groundbreaking advance in immunotherapy. While treatments like CAR-T cell therapy have shown incredible promise, they are not a solution for every patient, often because the necessary immune cells are rare or difficult to work with. Now, researchers have developed a “recipe book” that could change everything, allowing us to create powerful immune cells from more common cells, like those in our skin. This conversation will explore the intricate four-year journey to create this system, its potential to revolutionize treatments for cancer and autoimmune diseases, and the future of personalized medicine where therapies are tailor-made for each individual’s immune system.

You’ve developed a “recipe book” using a library of over 400 immune factors. Could you describe the four-year journey of creating this system and explain how DNA barcoding lets you efficiently test thousands of potential combinations for reprogramming cells?

It was an incredibly meticulous and foundational process that took four full years to complete. We were not just looking for one magic bullet; we needed to build an entire arsenal. We systematically identified and cataloged over 400 distinct factors known to influence immune cell identity. The real genius, though, is the DNA barcoding. Think of it like a unique barcode on every item in a massive supermarket. We attach a specific DNA tag to each of these 400 factors. This allows us to mix them into thousands of different combinations and introduce them to a population of cells. We can then “scan” the resulting cells and see exactly which “barcodes”—which factors—were present in the ones that successfully transformed. It turns a process that would have been impossibly slow into a highly efficient, large-scale screening platform.

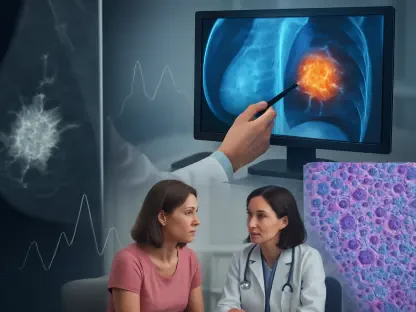

Current immunotherapies often depend on a patient’s own T cells, which can be difficult to extract or modify. How does your approach of reprogramming more accessible cells, like skin cells, solve this problem? Please share a hypothetical step-by-step journey for a patient.

This is one of the most significant advantages. Many patients who need immunotherapy are already weakened by disease, and their T-cell populations might be exhausted or simply too scarce to harvest effectively. Our approach bypasses that bottleneck entirely. Imagine a cancer patient for whom standard treatments have failed. Instead of a difficult blood draw to hunt for rare T cells, we could take a simple skin biopsy—a painless and straightforward procedure. We would then take those skin cells back to the lab and use our “recipe book” to reprogram them into, say, a large, healthy population of cancer-fighting immune cells. These newly generated cells, which are essentially the patient’s own but now repurposed, could then be infused back into their body to attack the tumor. This could open the door for so many people who are currently ineligible for these life-saving therapies.

Your platform successfully produced natural killer (NK) cells, a breakthrough for reprogramming. What makes NK cells so challenging to generate yet so critical for fighting cancer? Please elaborate on the significance of this and the other five immune cell “recipes” you’ve identified.

Generating NK cells through reprogramming has been a major hurdle in this field, which is what makes this achievement so exciting. NK cells are the immune system’s front-line sentinels; they are innately programmed to identify and destroy stressed or cancerous cells without prior sensitization, unlike T cells. Their power lies in this immediate, potent response. The difficulty has always been in understanding the complex cocktail of signals needed to coax another cell into becoming a fully functional NK cell. By cracking this recipe, we have unlocked a crucial tool for cancer therapy. The other five recipes we have identified are just as important for building a comprehensive therapeutic toolkit, as different diseases require different types of immune responses. Having a variety of cell types on demand is like having a full set of surgical tools instead of just a single scalpel.

Looking beyond oncology, you plan to address autoimmune diseases and tissue repair. How might the cellular “recipes” for these conditions differ from those for cancer? Could you provide a practical example of how this technology might be used to treat a specific autoimmune disorder?

The approach shifts fundamentally. For cancer, the goal is to create aggressive, killer cells to attack a foreign-acting invader. For autoimmune diseases, the goal is often the exact opposite: we need to calm the immune system down and stop it from attacking the body’s own tissues. So, the recipes would be completely different, designed to generate regulatory immune cells that suppress a hyperactive immune response. For instance, in a condition like rheumatoid arthritis, where the immune system attacks the joints, we could potentially generate and introduce specific regulatory cells that migrate to the joints and tell the other immune cells to stand down. This would be a living therapy that restores balance, rather than a drug that broadly suppresses the entire immune system, which often comes with severe side effects. The same logic applies to tissue repair, where we would want to create cells that manage inflammation and promote healing.

The ultimate goal is to create therapies tailored to an individual’s immune system. What are the key steps and potential obstacles in moving from discovering a universal “recipe” for a cell type to developing a personalized version that works for a specific patient?

This is the Holy Grail of this technology. Moving from a universal recipe to a personalized one involves several complex steps. First, we need to deeply understand a patient’s specific immune landscape—what is working, what is not, and why. This requires advanced diagnostics. The next step is to fine-tune the universal recipe. A patient’s genetic background and disease specifics might mean they need a slightly different combination of factors for the most effective reprogramming. The major obstacle is the sheer complexity and variability between individuals. Two people with the same cancer diagnosis can have wildly different immune responses. Overcoming this will require a massive amount of data, machine learning to identify patterns, and rigorous clinical testing to ensure these personalized therapies are both safe and more effective than the one-size-fits-all approach.

What is your forecast for immune cellular reprogramming?

My forecast is incredibly optimistic. We are standing at the edge of a new era in medicine where we can essentially program biology on demand. In the near term, this will dramatically expand our arsenal of immunotherapies for cancer, making them accessible to more patients. Looking further out, I see this platform becoming a cornerstone for treating a vast range of conditions, from autoimmune disorders to chronic inflammatory diseases and even regenerative medicine. The ultimate vision is a future where we can precisely engineer a patient’s own cells to create a living, dynamic therapy that perfectly matches their unique biological needs, effectively teaching the body to heal itself from within.