Today we’re joined by Ivan Kairatov, a biopharma expert with a deep understanding of the innovations shaping cancer research. His work delves into one of the most challenging frontiers in oncology: the intricate relationship between the nervous system and pancreatic cancer. We’ll explore how cutting-edge imaging techniques are revealing this connection in stunning detail, uncovering a destructive feedback loop that fuels pre-cancerous growth. We’ll also discuss a pivotal experiment that slashed tumor development by disabling specific nerve fibers and consider how these groundbreaking findings could lead to repurposing existing drugs for new therapeutic strategies.

The transition from 2D to 3D imaging can reveal surprising biological structures. Could you describe the dense nerve network you observed around pancreatic lesions using this advanced technique and elaborate on how that visual shift changed your understanding of the pre-cancerous environment?

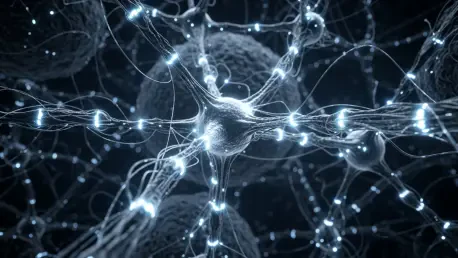

It was genuinely shocking. For years, we’ve relied on standard 2D imaging, which gives you these flat, thin slices of tissue. In those images, nerves just appear as tiny, scattered dots, seemingly insignificant. But when we used whole-mount immunofluorescence to build a 3D picture, the reality was breathtakingly different. Suddenly, we saw this incredibly dense network of nerve fibers actively snaking through and wrapping around the pre-cancerous lesions and the tumor-promoting fibroblasts. It wasn’t a passive background element; it was a fully integrated, complex architecture. That visual shift completely changed our perspective, forcing us to see the nervous system not as a bystander, but as an active and essential collaborator in the earliest stages of pancreatic cancer development.

Your work details a destructive feedback loop between specific fibroblasts and nerve cells. Could you walk us through this process step-by-step, from the initial signals to the resulting calcium spike, and explain how this cycle becomes dangerously self-reinforcing?

Certainly. It’s a classic vicious cycle that creates a perfect storm for cancer growth. It all starts with a specific type of fibroblast we call myCAFs. These cells act as beacons, sending out chemical signals that actively attract nerve fibers from the sympathetic nervous system—the network responsible for our “fight-or-flight” response. Once these nerves arrive and infiltrate the lesion, they release a neurotransmitter called norepinephrine. This chemical then binds directly to the myCAFs, triggering a dramatic calcium spike inside them. This spike is the critical event; it supercharges the fibroblasts, making them even more aggressive in promoting pre-cancerous growth. But crucially, it also makes them send out even stronger signals, which in turn pulls in more nerve fibers, locking the entire system into a dangerous, self-reinforcing loop that just accelerates the disease process.

In one experiment, disabling the sympathetic nervous system with a neurotoxin cut tumor growth by nearly 50%. Can you explain the mechanics behind this significant reduction and discuss what it reveals about the critical role these specific nerve fibers play in promoting cancer?

That experiment was a pivotal moment for us. By using a neurotoxin to selectively shut down the sympathetic nerve fibers, we essentially cut the power to that feedback loop I just described. Without the nerves releasing norepinephrine, the fibroblasts never received the signal to trigger the calcium spike. This meant the myCAFs were never fully activated, dramatically reducing their ability to create that cancer-friendly environment. Seeing tumor growth cut by nearly half was a stark confirmation of our hypothesis. It demonstrated unequivocally that these specific nerve fibers aren’t just incidentally present; they are a fundamental engine driving the progression from a pre-cancerous lesion to a full-blown tumor. Their influence is not minor—it’s a major pathway that cancer exploits.

The discovery that this nerve-fibroblast interaction occurs very early suggests new therapeutic windows. How might existing drugs, such as doxazosin, be repurposed to disrupt this cycle, and what would a combination therapy approach look like in practice for patients?

This is where the findings become incredibly promising for patients. Because this crosstalk happens so early, it gives us a new window to intervene before the cancer becomes aggressive and difficult to treat. We know that drugs like doxazosin, which are already clinically approved and available, work by blocking the receptors that norepinephrine binds to. The idea is to repurpose them to break that nerve-fibroblast communication link. In practice, this wouldn’t likely be a standalone treatment. Instead, we envision a combination therapy where a patient receives standard treatments like chemotherapy or immunotherapy to attack the cancer cells directly, while simultaneously taking a drug like doxazosin to disrupt the supportive microenvironment. By disabling this nerve-driven growth engine, we could make the primary therapies significantly more effective.

What is your forecast for pancreatic cancer treatment?

I am cautiously optimistic that we are on the cusp of a paradigm shift. For too long, we’ve focused almost exclusively on the cancer cells themselves. My forecast is that future treatments will increasingly adopt a more holistic, ecosystem-based approach. Instead of just targeting the “seed”—the tumor cell—we will also target the “soil”—the microenvironment that nourishes it. This means developing therapies that disrupt critical interactions, like the one between nerves and fibroblasts. I believe the next decade will see the rise of combination therapies that pair traditional cancer-killing agents with drugs that normalize the tumor microenvironment, cutting off the support systems that cancer relies on to grow, resist treatment, and spread. This multi-pronged strategy, I believe, holds the key to finally improving outcomes for patients with this devastating disease.