The promise of harnessing the body’s own immune system to fight cancer has been one of the most significant medical breakthroughs of the century, yet a persistent paradox has puzzled clinicians and researchers alike. For years, the prevailing wisdom held that tumors with more genetic mutations were more likely to respond to immunotherapy. This article delves into groundbreaking research that challenges this long-held belief, revealing a far more intricate and qualitative picture of cancer immunity. The objective is to explore the concept of mutational signatures and explain how the type of genetic error, not just the total number, is the critical factor in determining whether a tumor can be successfully targeted by the immune system.

Readers can expect to gain a clear understanding of why the “more is better” approach to tumor mutations is an oversimplification. The following sections will answer key questions about how specific mutational patterns make a tumor “visible” or “invisible” to immune cells. Furthermore, it will illuminate the crucial interplay between a tumor’s genetic fingerprint and a patient’s own unique immunogenetic makeup, paving the way for a new era of truly personalized cancer treatment.

Key Questions or Key Topics Section

Why Is a High Mutation Count Not Always Better

The concept of tumor mutational burden (TMB)—the total number of mutations within a cancer cell’s genome—has long served as a primary biomarker for predicting immunotherapy success. The logic seemed straightforward: more mutations would create more abnormal proteins, or neoantigens, which would act as red flags for the immune system. A higher TMB was therefore thought to increase the chances that at least some of these flags would be potent enough to trigger an effective anti-tumor response.

However, clinical experience has consistently shown that this quantitative measure is an unreliable predictor. Many patients with high-TMB tumors fail to respond to treatment, while some with a lower TMB show remarkable success. This inconsistency points to a fundamental flaw in the assumption that all mutations are created equal. Recent comprehensive analysis of thousands of cancer genomes confirms that simply counting mutations is not enough. The focus must shift from how many mutations exist to what kind of mutations they are and what effect they have on the immune system’s ability to recognize cancer.

What Are Mutational Signatures

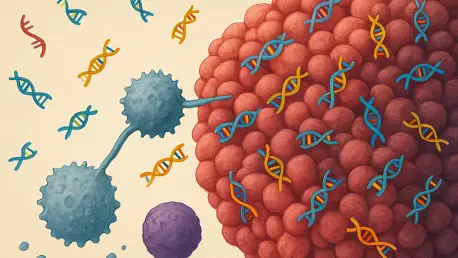

Mutational signatures are distinctive patterns of genetic errors found within a tumor’s DNA, which act like molecular fingerprints. These are not random assortments of mutations; rather, they fall into recurring, identifiable patterns that reveal the underlying cause of the mutations, such as exposure to specific carcinogens like tobacco smoke, defects in DNA repair machinery, or natural aging processes. A landmark study identified five dominant “amino acid substitution signatures” that account for the vast majority of mutations across many cancer types.

These signatures provide a qualitative lens through which to view a tumor’s genetic landscape. Instead of a simple tally, they offer a narrative about the tumor’s origins and its biological behavior. For example, one signature might be characterized by specific types of single-letter DNA changes, while another might involve small insertions or deletions. This classification is pivotal because each pattern has a different propensity for creating protein fragments that the immune system can recognize as foreign and dangerous.

How Do These Signatures Affect a Tumor’s Visibility

The ultimate impact of a mutational signature lies in its ability to shape a tumor’s “visibility” to the immune system. Some signatures consistently produce highly immunogenic neoantigens—mutated protein fragments that are effectively presented to immune cells and provoke a strong attack. Tumors dominated by these patterns are considered immunologically “hot,” as they are teeming with clear targets that mobilize the body’s defenses.

In contrast, other mutational signatures tend to generate neoantigens that are poorly recognized or presented by immune cells. These tumors are classified as “cold” because they can accumulate a high number of mutations without ever effectively alerting the immune system to their presence. This finding directly explains why a high TMB can be misleading; if the vast majority of a tumor’s mutations belong to a “cold” signature, the immune system remains blind to the threat, and immunotherapy is likely to fail. The quality and character of the neoantigens produced are far more important than their sheer quantity.

What Role Does a Patient’s Genetics Play

The visibility of a tumor is not determined by its mutational signature alone; the patient’s own genetic makeup plays a critical co-starring role. The presentation of neoantigens to T-cells, the soldiers of the immune system, is managed by a set of proteins called the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system. Since the HLA system is incredibly diverse across the human population, each person’s immune system has a unique capacity to “see” and respond to specific threats.

This means that a particular neoantigen might be effectively presented by one patient’s HLA type but completely ignored by another’s. The research shows that a patient’s HLA profile can sometimes compensate for a tumor’s “cold” mutational signature by being particularly adept at presenting the specific types of mutated peptides it produces. This interaction underscores the deeply personal nature of cancer immunity and highlights why a one-size-fits-all approach is insufficient. True personalization requires understanding both the tumor’s fingerprint and the patient’s unique immune framework.

Summary or Recap

The landscape of immunotherapy is undergoing a significant transformation, moving beyond simplistic quantitative metrics toward a more sophisticated, qualitative understanding of cancer. The central takeaway is that the type of mutation, defined by its signature, is a more powerful predictor of treatment response than the total number of mutations. This new framework explains why some tumors remain “cold” and unresponsive despite a high mutational burden.

This knowledge also emphasizes the dual importance of a tumor’s genetic characteristics and the patient’s individual immune system. The interplay between mutational patterns and a person’s HLA type creates a complex, personalized equation for predicting immunotherapy success. By analyzing both factors, clinicians can develop a much more accurate forecast, helping to guide treatment decisions more effectively.

Conclusion or Final Thoughts

The revelations about mutational signatures fundamentally refined the approach to cancer immunotherapy. The shift in focus from mutation quantity to quality provided a clear rationale for why some treatments succeeded while others failed, resolving a long-standing clinical puzzle. This understanding not only promised to improve patient selection for existing therapies but also opened new avenues for developing treatments that could turn “cold” tumors “hot.”

Ultimately, this research underscored the necessity of a deeply personalized strategy. The integration of a tumor’s mutational profile with a patient’s unique immunogenetics marked a critical step toward tailoring cancer care with unprecedented precision. This more nuanced model reduced the reliance on trial-and-error, offering a pathway to match the right patient with the right therapy from the outset, thereby improving outcomes and minimizing exposure to ineffective treatments.