A daily habit as ordinary as pouring a third or fourth cup of coffee may have aligned with a five-year edge in biological aging among people living with schizophrenia and mood disorders, hinting that moderation could matter more than any exotic supplement. The notion is surprising because coffee has long been loved, doubted, and studied from every angle, yet its role in cellular aging—especially in psychiatric populations—has rarely been tested head-on. Now evidence from a clinical sample suggests that three to four cups per day correlate with longer telomeres, the protective DNA caps that shorten with age and stress.

The draw of this finding is not the buzz of caffeine, but the possibility that a common beverage could intersect with a complex health gap. Individuals with severe mental disorders often face earlier onset of age-related disease and a shorter life span, and the biology behind that disparity has needed clearer clues.

Why this story matters now

Telomeres act like a biological clock, eroding bit by bit as cells divide and respond to inflammation and oxidative insults. Shorter telomeres are tied to higher risks for cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, and cognitive decline. In schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, multiple studies have documented comparatively shorter telomeres, reinforcing the concept of accelerated aging in these conditions.

Coffee, by contrast, tends to show up in research as a paradox: a stimulant associated with jittery nights but also with lower all-cause mortality, better metabolic profiles, and reduced risks of neurodegenerative disease at moderate intake. Prior work on coffee and telomeres in the general population has been mixed, with some analyses finding benefits and others finding neutral effects, making dose and context crucial.

The bridge between these threads arrived in new data linking coffee consumption and telomere length among adults with severe mental disorders. The headline is straightforward: moderate intake was linked to longer telomeres than no intake, a difference that translated to roughly five fewer years of biological aging. For a group facing marked health inequities, even incremental signals draw attention.

What the study examined and how it was done

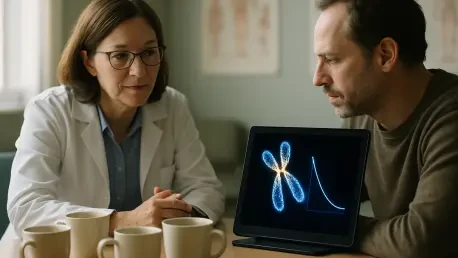

Researchers evaluated 436 adults diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum or affective disorders who were recruited from four psychiatric units in Norway. To reduce external noise, individuals with neurologic conditions, significant head trauma, or major medical illnesses that might alter brain function were excluded. Diagnoses were confirmed by trained clinicians using standardized assessments, and medication doses were recorded to model potential effects of antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and antidepressants.

Coffee was recorded through clinical interviews in four categories: none; one to two cups; three to four cups; or five or more cups per day. Smoking history was included because tobacco use drives oxidative stress and inflammation, both of which hasten telomere loss. Telomere length was measured in leukocytes as a T/S ratio and converted to base pairs, enabling an estimate of biological age equivalence.

Analyses relied on analysis of covariance to adjust for age, sex, ethnicity, smoking duration, and psychotropic dose. Sensitivity tests checked for interactions by sex or diagnosis and contrasted non-drinkers with a combined “recommended intake” group consuming one to four cups daily. The approach emphasized practical comparability: how did moderate real-world intake relate to a validated biomarker of aging in a clinical population?

What the data suggest and how experts interpret it

The pattern that emerged looked like an inverted J. Participants drinking three to four cups per day had significantly longer telomeres than non-drinkers after adjustment for confounders. Importantly, five or more cups offered no added benefit, suggesting that any positive effects plateau or even wane when intake becomes heavy. When one to four cups were grouped and compared against none, the difference approximated a five-year advantage in biological age.

The signal was steady across major subgroups. There was no evidence that sex or diagnostic category altered the association, implying that the curve held for both men and women and for schizophrenia and affective disorders alike. Coffee intake did not differ by sex or medication exposure, though individuals with schizophrenia reported higher average consumption than those with affective disorders. Notably, the heaviest coffee group skewed older and carried longer smoking histories, a combination that could dilute potential benefits.

Why might moderate coffee intake track with longer telomeres? One line of reasoning centers on bioactive compounds in coffee—polyphenols and other antioxidants—that temper oxidative stress and systemic inflammation, two drivers of telomere attrition. Another points to caffeine’s influence on cellular signaling and telomerase, the enzyme that helps maintain telomere length. In severe mental disorders, where inflammation and oxidative pressure are common, these mechanisms may be especially relevant. As one clinician familiar with the data put it, “the story seems to be less about stimulation and more about the cellular milieu that moderate coffee can shape.”

The findings also fit a broader pattern seen across coffee research: non-linear relationships. Moderate consumption often associates with favorable outcomes, while low or very high intake provides less consistent benefits. That curve appeared again here, with the sweet spot at three to four cups, reinforcing that “more” is not a synonym for “better.”

The study’s limitations deserve equal weight. Cross-sectional data cannot untangle cause and effect, and self-reported categories lack detail about cup size, roast, brewing method, or other caffeine sources. Lifestyle factors such as diet, sleep, and physical activity were not captured, nor were biomarkers of inflammation or oxidative stress that could validate mechanisms. Without a healthy control group, generalization beyond psychiatric populations remains uncertain, and averages across leukocyte types can obscure the shortest telomere fractions that may bear clinical risk.

What readers can do next and where research is heading

For clinicians, the takeaway is pragmatic rather than prescriptive. Coffee can be discussed as part of a lifestyle conversation, with moderate intake—about three to four cups a day—framed as potentially compatible with healthier biological aging in severe mental disorders. That conversation should include screening for insomnia, anxiety, cardiac arrhythmias, reflux, pregnancy, and medication interactions. It should also sit alongside guidance on sleep, exercise, nutrition, and smoking cessation, which carry larger and better-established effects on morbidity and mortality.

For patients and caregivers, the message is to favor moderation and self-awareness. If coffee is already part of the day, staying within one to four cups may be a reasonable target, ideally earlier in the daytime to protect sleep. Tracking personal responses—restlessness, palpitations, heartburn, or changes in anxiety—helps calibrate the dose. Brewing choices matter for some cardiometabolic profiles; filtered coffee, for instance, can reduce certain lipid-raising compounds compared with unfiltered methods.

In practice, a simple framework can guide decisions. Start by assessing current intake and sensitivity, including sleep quality and anxiety levels. If appropriate, nudge consumption toward one to four cups, with three to four as a typical upper bound. Monitor symptoms and any shifts in medication effects, and adjust in consultation with clinicians. Pair this routine with habits that independently support telomere maintenance, such as regular physical activity, nutrient-dense meals, stress management, and smoking cessation.

The next wave of research would profit from longitudinal designs that track specific coffee types, brewing methods, cup sizes, and co-exposures over time. Integrating panels of inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers would test mechanisms head-on, while telomerase assays and cell-type–specific telomere measurements would sharpen biological resolution. Including healthy controls would clarify whether the observed pattern is unique to psychiatric populations or part of a general human response to moderate coffee consumption. Randomized trials, where feasible and ethical, could help isolate dose-response effects and separate coffee’s compounds from caffeine’s impact.

In the end, the latest evidence pointed to a measured conclusion: moderate coffee intake aligned with longer leukocyte telomeres in adults with severe mental disorders, echoing other non-linear health patterns seen with coffee. It reframed an everyday ritual as a potentially meaningful lever within broader care, encouraged careful attention to dose and individual tolerance, and set the stage for studies that could turn an intriguing association into actionable guidance.