The allure of a cut-price cosmetic procedure or weight-loss surgery abroad often masks a harsh reality, one where complications can leave UK patients facing a health crisis and the National Health Service footing a bill that can spiral into tens of thousands of pounds. This growing trend of “outward medical tourism” is creating a significant, yet poorly documented, financial and resource drain on the NHS. As more residents seek elective surgeries overseas, a troubling paradox emerges: the system designed to care for them back home is increasingly burdened by the fallout, operating within an information vacuum that obscures the true scale of the risk and cost.

The Price of Complications and the Question of Responsibility

When an elective procedure performed in another country goes wrong, the financial repercussions for the UK’s public health system can be staggering. A comprehensive review of available data revealed that the cost to manage a single patient’s postoperative complications ranged from £1,058 to a shocking £19,549. These figures, adjusted for current prices, represent a direct transfer of financial burden from a private consumer choice to the publicly funded NHS. The costs cover everything from extended hospital stays and additional surgeries to complex diagnostic tests and long-term outpatient care, transforming an overseas bargain into an expensive domestic problem.

This situation raises a central and complex question of financial responsibility. The NHS is obligated to provide emergency and necessary care to all eligible residents, regardless of the circumstances leading to their condition. However, the escalating costs associated with correcting elective surgeries performed abroad challenge the boundaries of this responsibility. As the number of cases grows, it forces a difficult conversation about where personal liability ends and public duty begins, particularly for non-emergency follow-up care that falls into a gray area of clinical necessity.

A Surge in Popularity Amid a Dangerous Lack of Data

The practice of traveling abroad for medical procedures has seen a steady rise in popularity among UK residents over the last decade, a trend that shows no signs of slowing. Driven by lower costs, shorter waiting times, and the promise of specialized care, thousands of individuals now venture overseas each year for surgeries ranging from bariatric procedures to cosmetic enhancements. This global marketplace for health care offers undeniable appeal, but it operates largely outside any regulatory oversight that could track its impact back home.

This surge in medical tourism has created a dangerous paradox: while more people are undertaking these journeys, the systematic collection of data on adverse outcomes has failed to keep pace. This creates a critical information void, leaving both prospective patients and NHS planners in the dark about the true frequency and nature of complications. Without comprehensive tracking, it is nearly impossible to quantify the risks involved, understand the full strain on NHS resources, or develop effective strategies to mitigate the consequences.

A Closer Look at the Patients and Procedures Involved

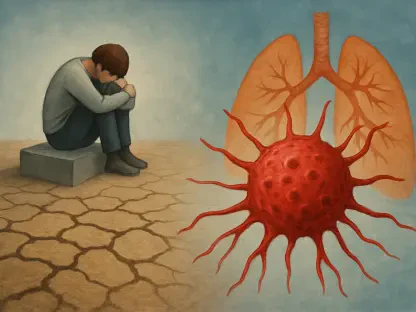

An analysis of 655 cases treated by the NHS between 2011 and 2024 for complications paints a clear demographic picture. The patient profile is overwhelmingly female, accounting for 90% of individuals, with an average age of 38. While patients traveled to 29 different countries, Turkey emerged as the dominant destination by a significant margin, representing 61% of all reported cases. The procedures most frequently leading to complications included sleeve gastrectomy, a form of weight-loss surgery, followed by cosmetic surgeries such as breast augmentation and abdominoplasty, or “tummy tucks.”

The toll on the health system extends far beyond the initial bill. The data revealed that over half of the patients (53%) suffered from complications classified as moderate to severe. These issues often necessitated extensive use of NHS resources, including lengthy and costly hospital stays. For those returning from metabolic surgery, the average inpatient stay was over 17 days, with one patient requiring 45 days of continuous care. Cosmetic surgery complications resulted in an average stay of nearly 6 days, though one case extended to 49 days. Moreover, these figures do not capture the unrecorded costs of operating room time, numerous diagnostic tests, and dozens of outpatient appointments required for long-term recovery.

Underestimating the True Scale of the Problem

Researchers have stressed that the certainty of the available evidence is low, strongly suggesting that official figures drastically underestimate the true scope of the issue. The vast majority of the studies reviewed were retrospective, relying on patient medical notes that were often incomplete, inconsistently coded, or lacking in crucial details about a patient’s prior medical history. This reliance on fragmented records means that both the rate of complications and the associated costs are likely to be significantly higher than what has been documented.

The current body of evidence also suffers from major blind spots that further obscure the full picture. There is a notable lack of data from certain geographic regions of the UK, including Wales and the South West of England. Furthermore, the analysis found no eligible studies concerning other popular specialties for medical tourism, such as orthopedic surgery. The focus has remained on hospital-based care, leaving the significant impact on primary care settings—where many patients first seek help—entirely unmeasured and unrecorded.

Toward a Safer Future Through Systemic Change

In light of these findings, experts insist that a systematic approach to data collection is imperative for navigating this complex issue. They have strongly advocated for the implementation of a national system to systematically track how many UK residents travel abroad for elective surgery and, crucially, how many subsequently require NHS care for complications. Such a registry would provide the high-quality data needed to understand the risks, anticipate the demand on health services, and inform public policy.

Alongside better data collection, there is a pressing need for proactive measures to protect both patients and the NHS. This includes the development of targeted public awareness campaigns designed to educate prospective medical tourists about the potential for severe complications and the often-overlooked complexities of arranging follow-up care in the UK. Furthermore, clear guidance is needed to delineate the NHS’s responsibilities versus the potential for personal financial liability for non-emergency treatments, ensuring patients are fully informed of the consequences before they travel.

The evidence, though incomplete, painted a clear picture of a growing challenge that could no longer be ignored. The findings underscored the urgent need for a cohesive national strategy—one that balanced patient choice with the fiscal and operational realities of the health service. Ultimately, any path forward had to aim to protect both the individuals seeking care and the vital public institution tasked with their well-being.