The successful conclusion of cancer treatment should be a moment of pure triumph, yet for many, it signals the start of a lifelong struggle with chronic, painful tissue damage—a silent epidemic born from the very therapy that saved them. While radiotherapy stands as a pillar of modern oncology, its power comes at a cost, often leaving a lasting legacy of scarred tissue that diminishes the quality of life for millions of survivors. This long-standing challenge has pushed scientists to look deeper into the cellular mechanisms of radiation damage, and a recent breakthrough suggests a single protein may hold the secret to preventing this debilitating side effect, potentially rewriting the future of post-cancer recovery.

The Unseen Cost of a Cure

Radiotherapy is a profoundly effective weapon against cancer, using high-energy radiation to destroy malignant cells and shrink tumors. Its life-saving capacity is undisputed. However, this powerful treatment is a double-edged sword. The radiation cannot perfectly distinguish between cancerous and healthy tissue, leading to unavoidable collateral damage in the surrounding areas. This incidental exposure sets off a complex biological response that can lead to severe, long-term complications, turning the victory over cancer into a new, protracted battle for physical comfort and normalcy.

Among the most common and distressing of these after-effects is radiation-induced fibrosis. This condition is essentially an overactive scarring process where healthy, flexible tissue is gradually replaced by a dense, hard matrix of fibrous connective tissue. Following radiotherapy to the skin, this process can transform supple tissue into a painful, tight, and functionally impaired area. For patients, this is far more than a cosmetic issue; it represents a constant, physical reminder of their treatment that can persist for years, or even a lifetime.

Living with fibrosis profoundly impacts a patient’s daily existence. The affected skin often becomes hypersensitive, prone to pain, and subject to restricted movement, particularly when near joints. Unfortunately, the medical community has historically been limited in its ability to address the problem at its source. Current therapeutic strategies focus primarily on managing the symptoms—using moisturizers to soothe dryness, physical therapy to maintain mobility, and pain medication to provide comfort. While helpful, these interventions do not halt or reverse the underlying fibrotic process, creating a significant therapeutic gap and a clear need for a solution that can prevent the damage before it becomes permanent.

Unmasking a Molecular Culprit

A groundbreaking discovery from a collaborative German research team has illuminated the primary driver of this damaging process. Scientists from LMU University Hospital and the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) successfully pinpointed a single protein, Dickkopf 3 (DKK3), as the molecular culprit responsible for initiating the cascade that leads to fibrosis. By combining insights from mouse models, human cell cultures, and tissue samples from patients, the researchers meticulously traced the pathway of radiation damage, moving beyond symptom observation to identify a specific, actionable target.

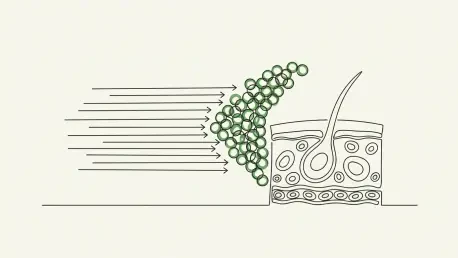

The investigation revealed that the destructive chain of events begins in the skin’s outermost layer. Following radiation exposure, a specific subset of skin cells called keratinocytes are triggered to produce and release DKK3. This protein, once activated, acts as a powerful signaling molecule that fundamentally alters the cellular environment. It initiates a pro-inflammatory response that, instead of promoting healing, incites the gradual hardening and thickening characteristic of fibrotic tissue. This work established a clear, linear progression from the initial radiation trigger to the activation of DKK3 and finally to the development of chronic skin damage.

The strength of these findings lies in the comprehensive evidence gathered across multiple experimental platforms. In laboratory mouse models, the presence of DKK3 was directly correlated with the severity of skin fibrosis after radiation. These observations were further validated in human cell cultures, which allowed the team to map the precise molecular interactions at play. Most critically, analysis of tissue from cancer patients who had undergone radiotherapy confirmed that the same DKK3-driven mechanism was present, solidifying the protein’s central role in this widespread clinical problem.

Beyond the Skin a Universal Mediator

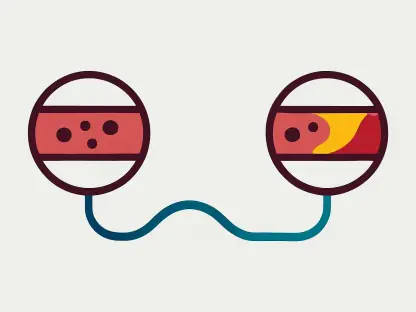

The implications of this research extend far beyond dermatological damage. As Professor Peter Nelson of LMU noted, the team observed analogous fibrotic processes mediated by DKK3 in other organs, including the kidney. This crucial finding suggests that the protein is not just a skin-specific actor but may be part of a fundamental biological pathway for tissue scarring in response to injury throughout the body. Fibrosis is a common final pathway in many chronic diseases affecting the lungs, liver, and heart, and this discovery could provide a unifying therapeutic target.

This research, built upon the foundational contributions of team members including LMU students Li Li and Khuram Shehzad, represents more than just an incremental advance; it offers a new conceptual framework for understanding post-radiation injury. By identifying a single, upstream trigger, the discovery paves the way for interventions that could preemptively stop the damage. The focus can now shift from managing the consequences of fibrosis to preventing its onset, a paradigm shift that could transform long-term patient outcomes.

Expert analysis underscores the significance of identifying DKK3 as a central mediator. For decades, the mechanisms behind radiation fibrosis were thought to be overwhelmingly complex and diffuse, making the development of a targeted therapy seem distant. The discovery of a primary initiator simplifies this picture dramatically. It provides a clear, “druggable” target that was previously hidden within a web of complex cellular signals, offering a tangible path toward a new class of preventative medicines.

Charting a New Course for Patient Care

With a definitive target identified, the research team is now focused on the next logical frontier: developing drugs that can neutralize DKK3. The goal is to engineer specific DKK3 blockers—molecules that can bind to the protein and inhibit its activity before it can trigger inflammation and fibrosis. As Professor Nelson stated, “Drugs that block DKK3 could one day help prevent or reduce long-term skin damage after radiotherapy.” Such a treatment could be administered alongside or shortly after radiation therapy, acting as a protective shield for healthy tissue.

The development of DKK3 inhibitors has the potential to fundamentally reshape the management of radiotherapy side effects. Instead of waiting for irreversible damage to occur and then attempting to mitigate the symptoms, clinicians could adopt a preventative strategy. This proactive approach would not only spare patients from years of pain and discomfort but also improve the overall safety profile of radiotherapy, potentially allowing for its use in a wider range of clinical scenarios.

Moreover, the promise of DKK3-targeted therapies is not confined to cancer treatment. Given the evidence that this protein plays a role in fibrosis in other organs, a successful DKK3 blocker could have broad applications in treating a host of other fibrotic diseases. Conditions such as pulmonary fibrosis, liver cirrhosis, and chronic kidney disease, which are collectively responsible for a significant burden of disease worldwide, could all potentially benefit from a therapy that targets this core mechanism of tissue scarring.

This pivotal research did more than just decipher a key mechanism behind a common clinical problem; it laid the essential groundwork for a new class of therapies aimed at enhancing the long-term well-being of millions. The identification of DKK3 has provided a clear and promising path forward, offering hope that the enduring physical scars of cancer treatment may one day become a relic of the past, allowing survivors to not only live but to thrive.