A groundbreaking study led by scientists at The Wistar Institute marks a significant leap forward in the decades-long search for an effective HIV vaccine, demonstrating that a novel vaccine candidate can induce neutralizing antibodies after just a single immunization in nonhuman primates. This achievement, detailed in the prestigious journal Nature Immunology, represents a paradigm shift in vaccine design, offering the potential for dramatically simplified and more accessible vaccination protocols to combat the global HIV/AIDS epidemic.

A New Dawn in HIV Vaccine Research

Overcoming a Decades-Old Hurdle

For more than four decades, the human immunodeficiency virus has presented a formidable challenge to vaccinologists due to its remarkable ability to mutate and evade the body’s immune defenses. The primary goal in HIV vaccine development has been to elicit the production of broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs), which are specialized immune proteins capable of recognizing and inactivating a wide range of diverse HIV strains. However, achieving this has proven exceptionally difficult. Previous experimental vaccine strategies have followed complex and prolonged schedules, often requiring seven, eight, or even ten separate injections administered over the course of a year or more. Even with these intensive efforts, the immune responses generated were frequently weak, narrow, and slow to develop, leaving researchers searching for a more effective approach. This history of frustratingly incremental progress is what makes the recent breakthrough so scientifically significant; it shatters the long-held belief that a powerful initial antibody response was beyond the reach of a single-dose regimen.

The practical difficulties associated with multi-dose vaccination protocols have long been a major barrier to creating a globally viable HIV vaccine. A regimen requiring numerous clinic visits over an extended period presents significant logistical and financial challenges, particularly in resource-limited regions where the HIV burden is highest. Patient adherence becomes a critical issue, as incomplete vaccination schedules can compromise or nullify any potential protective effect. Furthermore, the cost of manufacturing and distributing multiple doses, along with the infrastructure needed to administer them, places a heavy strain on public health systems. The Wistar Institute’s approach, which prompts a foundational immune response with unprecedented speed and efficiency, directly addresses these real-world obstacles. As Dr. Amelia Escolano, the study’s senior author, highlights, the observation of neutralization after just one dose is a first in the field. This initial response was then substantially amplified with only one booster, suggesting a pathway toward a powerful and practical vaccine that is both faster and more efficient.

The Power of the WIN332 Immunogen

The centerpiece of this research is an innovative immunogen named WIN332, which was meticulously engineered to provoke a specific and powerful immune reaction. An immunogen is the active component of a vaccine that stimulates the immune system, and WIN332 was designed to target a critical region on the surface of the HIV virus known as the envelope protein. Unlike its predecessors, which often struggled to present the right viral targets in a way that the immune system could effectively recognize, WIN332 was built on a novel hypothesis about how to train immune cells to produce the most desirable antibodies. The success of this single immunogen in eliciting a neutralizing response so quickly is a testament to the precision of its design. It demonstrates that a well-crafted molecular signal can guide the immune system more efficiently than the brute-force approach of repeated exposures to less-optimized immunogens. This level of efficacy from a primary dose suggests that the foundation for a protective immune memory can be laid far more rapidly than previously thought possible.

The promising results seen with WIN332 were not limited to the initial immunization. When researchers administered a single booster shot using a related immunogen, the levels of neutralizing antibodies increased significantly, showcasing the immunogen’s ability to not only initiate but also effectively mature the immune response. This “prime-boost” strategy is a common feature of modern vaccine design, but the efficiency observed in this study is exceptional. The ability to achieve a robust and broadened antibody response with just a two-dose schedule represents a major advancement. According to Dr. Ignacio Relano-Rodriguez, the study’s first author, this streamlined approach could drastically simplify vaccination protocols, potentially achieving full immunity with as few as three injections in a clinical setting. Such a condensed schedule would not only improve patient compliance but also accelerate the timeline for achieving population-level immunity in vaccination campaigns, marking a pivotal step toward global HIV prevention.

Redefining the Rules of Engagement

Challenging Scientific Dogma

The core innovation of the Wistar team’s research lies in its deliberate challenge to a long-standing scientific dogma in HIV vaccine design. For many years, the scientific community focused on the virus’s envelope protein, specifically a region known as the V3-glycan epitope, as the primary target for a vaccine. It was widely believed that a particular sugar molecule, N332-glycan, which sits on this epitope, was absolutely essential for the binding of protective antibodies. This consensus was so entrenched that it guided nearly all previous immunogen designs; researchers meticulously engineered their vaccine candidates to preserve this N332-glycan structure, assuming its presence was non-negotiable for success. Dr. Escolano’s team, however, questioned this foundational assumption. They theorized that this glycan might be acting as a form of camouflage, diverting the immune system’s attention and preventing it from developing the most potent antibodies. This led them to pursue a highly counterintuitive and audacious strategy that went against decades of conventional wisdom.

The team’s radical approach involved completely removing the N332-glycan from the envelope protein to create their WIN332 immunogen. This was a significant scientific gamble, as it risked creating a vaccine candidate that would fail to elicit any relevant immune response at all. The underlying hypothesis was that by stripping away this key sugar molecule, they could force the immune system to recognize the underlying protein structure of the epitope more directly. This, they hoped, would lead to the generation of different, and potentially more effective, types of antibodies that did not depend on the glycan for binding. This departure from established principles was not just a minor tweak but a fundamental re-imagining of how to engage the immune system in the fight against HIV. It was a calculated risk based on a deep understanding of immunology, and it ultimately unlocked a new pathway toward a successful vaccine that had been hidden in plain sight. The remarkable results validated their unconventional strategy, proving that sometimes the most significant progress comes from daring to question established truths.

Uncovering a New Class of Antibodies

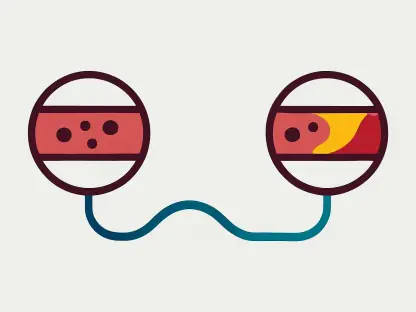

A secondary, yet equally significant, outcome of this research was a fundamental new discovery about the nature of HIV-neutralizing antibodies. By engineering an immunogen that lacked the N332-glycan, the team was able to reveal the existence of two distinct classes of antibodies that target the V3-glycan region. The first class, which they designated Type I, represents the previously known antibodies that are dependent on the N332 sugar for effective binding. These are the antibodies that past vaccine strategies had tried, with limited success, to elicit. The second, newly identified class, designated Type II, is capable of binding to and neutralizing the virus without requiring the presence of the N332-glycan. The discovery of these Type II antibodies is a major finding, as it expands the known repertoire of immune weapons that can be elicited to fight HIV. It shows that the immune system has more than one way to attack this critical viral site, providing a new and previously unrecognized vulnerability that can be exploited.

This insight provides vaccinologists with a new target and a broader toolkit for designing future vaccines intended to provide comprehensive protection against the vast genetic diversity of HIV strains circulating globally. The existence of Type II antibodies suggests that an effective vaccine may not need to perfectly mimic the natural virus but can instead guide the immune system toward developing unconventional but highly effective weapons. Future vaccine strategies could now be designed to specifically elicit these non-glycan-dependent antibodies, potentially in combination with Type I antibodies, to create a multi-pronged attack that the virus would find much harder to evade. This deeper understanding of the molecular interactions between antibodies and the virus is invaluable, moving the field beyond a trial-and-error approach and toward a more rational, mechanism-based design of next-generation HIV immunogens. The discovery essentially opens a new chapter in HIV vaccine research, armed with fresh knowledge and a new set of molecular targets.

A Pivotal Step Forward

The research from The Wistar Institute represented a multi-faceted breakthrough in the long and challenging journey toward an HIV vaccine. By boldly challenging established scientific assumptions, the team engineered the novel WIN332 immunogen and, in doing so, achieved the rapid elicitation of neutralizing antibodies after a single dose in a preclinical model. This success not only validated a new and highly efficient vaccination strategy but also led to the discovery of a new class of non-glycan-dependent antibodies, expanding the scientific community’s understanding of how to combat the virus. The promising results garnered significant interest from major global health organizations, which explored pathways to advance WIN332 into human clinical trials. While further preclinical work continued, this study stood as a pivotal and hopeful step toward developing a safe, effective, and globally accessible HIV vaccine.