The persistent feeling of being physically older and less resilient following a serious illness is no longer just a subjective complaint but is now understood as a tangible biological process driven by cellular damage. Many who recover from infections like influenza or COVID-19 report lingering fatigue and a sense that their bodies have been fundamentally changed. This phenomenon has catalyzed a new line of scientific inquiry, leading to the development of a unifying theory known as “Infection-Driven Senescence” (IDS), which posits that acute sickness can permanently accelerate aging at a cellular level and lay the groundwork for chronic disease.

The Lingering Shadow of Sickness

The central question researchers are now addressing is whether common illnesses can permanently age our bodies. The concept of Infection-Driven Senescence (IDS) provides a compelling framework, suggesting that the fight against a pathogen leaves a lasting scar on our cells. This theory connects the immediate experience of being sick with the long-term consequences of accelerated aging and an increased risk for chronic health conditions. It reframes recovery not as a simple return to baseline but as a transition to a new, potentially older biological state.

This emerging field suggests that the inflammation and cellular stress caused by an infection can push a significant number of cells into a state of premature aging. These “aged” cells do not die off as they should but instead linger in tissues, disrupting normal function and contributing to the feeling of being “older” than one’s chronological age. The IDS model offers a new lens through which to view the long-term health impacts of infectious diseases, moving beyond the acute phase of illness to consider its enduring legacy.

Cellular Aging Is Not Just About Time Anymore

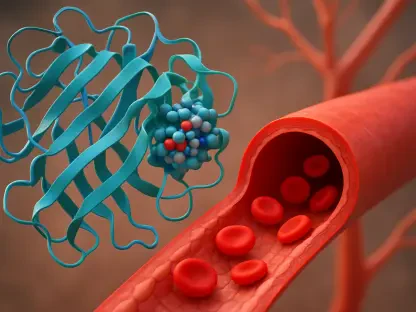

Cellular senescence is a biological state in which a cell permanently stops dividing but remains metabolically active. Instead of dying, it begins to secrete a cocktail of inflammatory molecules, growth factors, and enzymes. This process, often referred to as the Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP), is a natural part of aging and can serve protective functions, such as preventing damaged cells from becoming cancerous.

However, this mechanism is a double-edged sword. While the inflammatory response can help trap and clear pathogens during an active infection, an accumulation of senescent cells creates a state of chronic, low-grade inflammation. This “inflammaging” can impair tissue repair, disrupt organ function, and create an environment conducive to age-related diseases. The persistence of these “zombie cells” after an infection is resolved explains why tissues may not heal properly and why individuals feel a persistent sense of decline.

The Pathogen Playbook for Triggering Premature Aging

Respiratory viruses, in particular, have been shown to be potent inducers of senescence. Studies on both influenza and SARS-CoV-2 have demonstrated that these viruses trigger a robust senescent response in lung cells. This cellular state is directly linked to the persistent inflammation and impaired lung repair seen in some patients, potentially explaining long-term respiratory symptoms and conditions like pulmonary fibrosis. The damage is not just temporary; it is a lasting alteration to the cellular landscape of the lungs.

This phenomenon is not limited to acute viral illnesses. Chronic viruses like HIV and human cytomegalovirus (CMV) exert a sustained pressure on the body, pushing immune and vascular cells into a state of senescence over time. This mechanism helps explain why individuals with HIV, even with effective antiviral treatment suppressing the virus, often experience accelerated aging, including an earlier onset of cardiovascular disease and cognitive decline. The constant immune activation required to manage these infections takes a long-term toll.

Moreover, the connection extends beyond viruses to bacterial infections. Research on the bacterium Mycobacterium abscessus, for instance, has shown it induces senescence in immune cells. This process not only amplifies local inflammation but also paradoxically makes the host more susceptible to subsequent infections by disrupting normal immune function. This finding highlights a universal strategy used by diverse pathogens to manipulate the host’s cellular machinery for their own benefit, at the cost of the host’s long-term health.

Unlocking the Mechanism at a Landmark Conference

Breakthroughs in this field were a central theme at the 10th International Cell Senescence Association (ICSA) conference in 2025. As reported in the journal Aging-US, researchers presented a unifying finding: a wide range of pathogens consistently activate core senescence pathways, including p16INK4a, p21, and the crucial inflammatory hub, NF-κB. This consensus established that IDS is not a series of isolated events but a common biological response to infectious threats.

Compelling evidence from experimental models reinforced this conclusion. Studies presented at the conference demonstrated that therapeutically removing senescent cells after an infection led to tangible benefits. In models of respiratory infection, clearing these cells improved lung repair and function. In bacterial infection models, the same strategy resulted in reduced bacterial levels, suggesting that senescent cells can create a hospitable environment for pathogens. The conference solidified IDS as a critical field of research, providing a new framework for understanding the long-term consequences of infectious diseases.

A New Frontier in Medicine to Reverse Infection-Driven Damage

The growing understanding of IDS has opened a new therapeutic frontier focused on targeting senescent cells to mitigate or even reverse infection-driven damage. This has led to the development of senotherapeutics, a novel class of treatments designed to combat cellular senescence. These therapies represent a proactive approach to managing the long-term health of individuals post-infection, aiming to restore tissue function rather than merely managing symptoms.

This emerging field employs a two-pronged strategy for intervention. The first approach involves senolytics, which are drugs designed to selectively seek out and destroy senescent cells. By clearing these harmful cells, senolytics allow for healthy cells to repopulate the tissue, thereby promoting repair and reducing chronic inflammation. The second strategy utilizes senomorphics, which are compounds that do not kill senescent cells but instead neutralize their harmful inflammatory secretions, effectively disarming them.

The promise of these interventions was underscored by preclinical successes highlighted at the ICSA conference. Both senolytic and senomorphic strategies showed significant potential to reduce tissue damage and chronic inflammation in various post-infection models. The insights presented at the conference fundamentally shifted the understanding of post-infection recovery and illuminated a clear path toward developing treatments that could one day help people not only survive infections but also maintain their biological youth.