For individuals with compromised immune systems, such as those recovering from intensive cancer treatments, the common herpes simplex virus can transform from a manageable nuisance into a severe, life-threatening adversary. The clinical challenge intensifies dramatically when the virus evolves resistance to standard antiviral medications, leaving physicians with a dwindling arsenal of effective treatments. This mounting frustration within the medical community has spurred a dedicated search not just for new drugs, but for a profound understanding of how they can defeat a virus at the most fundamental level. A landmark study has now provided that understanding, leveraging state-of-the-art imaging technologies to capture the precise moment a new class of antivirals brings viral replication to a standstill.

A New Target for an Old Foe

The rise of drug-resistant herpes simplex virus strains presents a significant hurdle in infectious disease management, particularly for vulnerable patient populations. Standard, FDA-approved antivirals primarily work by targeting the virus’s DNA polymerase, the enzyme tasked with copying the viral genome. However, prolonged exposure to these drugs can inadvertently select for viral mutations that render this mechanism ineffective. Clinicians treating patients with weakened immune systems have witnessed firsthand the dire consequences of these resistant infections, where a treatable condition becomes a dangerous complication. This urgent clinical need has driven researchers to explore entirely new antiviral strategies that can bypass existing resistance pathways and offer a reliable line of defense for those most at risk, aiming to dissect the virus’s core machinery to uncover novel points of attack.

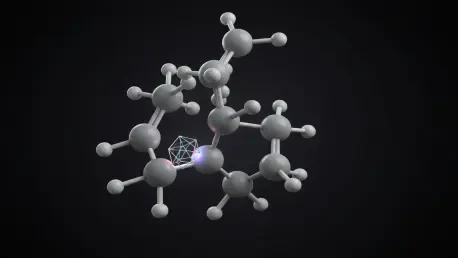

In response to this challenge, scientists have focused on an emerging class of drugs known as helicase-primase inhibitors (HPIs). These compounds represent a promising alternative because they attack a different and equally essential component of the virus’s replication machinery. The target of these drugs, the helicase-primase enzyme complex, is indispensable for the herpesvirus to multiply. This complex executes two perfectly coordinated functions. First, the helicase acts as a molecular motor, traveling along the double-stranded viral DNA and actively unzipping the two strands. This unwinding exposes the genetic code for copying. Immediately after, the primase function synthesizes a short RNA molecule that serves as a “primer,” providing the necessary starting point for the DNA polymerase to attach and begin its work. By disabling this two-part system, HPIs halt viral replication before it can even begin in earnest.

A Pioneering View of Molecular Sabotage

To achieve a comprehensive understanding of the drug’s effect, researchers employed a powerful combination of two distinct, cutting-edge imaging techniques. This dual approach was designed to capture both high-resolution static images of the drug’s interaction with the enzyme and a dynamic, real-time observation of the inhibition process as it unfolded. The first method, cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM), was used to obtain a structural blueprint. A major challenge in imaging the helicase-primase enzyme is its inherent flexibility; its constantly moving and changing shape makes it difficult to capture a clear image. Ingeniously, the researchers turned this problem into a solution. The HPI drugs, by their very nature as inhibitors, lock the enzyme into a single, static conformation upon binding. This stabilized drug-enzyme complex could then be imaged with incredible clarity, providing a near-atomic resolution view that revealed the precise physical and chemical interactions between the drug and its target.

While the cryo-EM images provided an invaluable structural map, the researchers needed to see the dynamic process of inhibition to confirm their findings. For this, they turned to a sophisticated technology known as optical tweezers, which utilizes highly focused laser beams to manipulate microscopic objects, akin to a miniature tractor beam. In a meticulously designed experiment, a single piece of viral DNA was suspended between two microscopic beads. The helicase-primase enzyme was then attached to the DNA, allowing the team to watch in real time as individual helicase molecules began to unwind the double helix. After observing the enzyme in its natural working state, they introduced small amounts of an HPI drug into the system. The effect was both immediate and clear. The team directly witnessed the inhibitor disabling the enzyme’s motor function, causing it to stall on the DNA strand. This experiment provided the “moving pictures” that perfectly complemented the static images from cryo-EM.

From Observation to Innovation

The synthesis of these two powerful imaging methods provided an unprecedentedly detailed account of how a new class of antiviral drugs functions. The static snapshots from cryo-EM revealed the exact structural binding sites, showing precisely how the HPI drugs interlock with the helicase-primase enzyme to disable it. Concurrently, the real-time observations from the optical tweezers demonstrated the functional consequence of this binding, showing the enzyme’s motor grinding to a halt. This research went far beyond simply confirming that a drug works; it successfully illustrated the entire mechanism of action, from the atomic-level chemical interaction to the ultimate failure of a key molecular machine. This holistic view provides a complete narrative of how the inhibitor effectively sabotages the viral replication process at one of its earliest and most critical stages.

This detailed molecular knowledge fundamentally shifted the landscape for future antiviral development. Armed with a precise understanding of how HPIs function, scientists could now engage in the rational design and optimization of more potent and specific drugs. The structural data not only explained the success of current HPIs but also illuminated new possibilities for creating next-generation inhibitors. Furthermore, the visualization of the entire replication fork assembly revealed additional sites within the larger viral machinery that could be targeted by entirely new classes of drugs. This foundational research provided the crucial insights needed to outmaneuver drug-resistant herpes, and it laid the groundwork for developing novel therapies against other DNA viruses that rely on similar replication mechanisms, ultimately offering new hope for improving the health of vulnerable patients worldwide.