Diving into the mysteries of the human brain, I’m thrilled to sit down with a leading expert in neuroscience whose groundbreaking work has reshaped our understanding of brain plasticity and adult neurogenesis. As a full professor at the University of Amsterdam and head of the Brain Plasticity group, this scientist has spent decades exploring how our brains adapt to stress, aging, and diseases like depression and dementia. From personal experiences that ignited a passion for brain research to pioneering discoveries about new neuron formation in adult brains, their journey offers profound insights into resilience and recovery. In this conversation, we’ll explore the emotional roots of their career, pivotal moments of scientific discovery, the impact of early life experiences on brain health, and innovative approaches to tackling complex neurological disorders. Join us as we uncover the science and stories behind how our brains adapt to life’s challenges.

How did a personal family experience with dementia spark your journey into brain research, and what emotions or specific moments from that time continue to drive your work on brain plasticity today?

Watching my uncle battle dementia was a deeply personal and transformative experience that set the course for my entire career. I remember sitting by his bedside, feeling this overwhelming mix of helplessness and curiosity as I saw him fade—his memories, his personality, just slipping away. There was one particular moment when he looked at me and couldn’t recall my name; the pain of that disconnection hit me hard, but it also ignited a fire to understand what was happening inside his brain. It wasn’t just sadness—it was a desperate need to find answers, to figure out if the brain could somehow fight back against such loss. That emotional weight carried me into my doctoral work, where I started exploring the idea of “use it or lose it,” the notion that activating brain cells might protect them from aging and disease. Even now, decades later, when I’m in the lab or analyzing data on brain plasticity, I think of him and that promise I made to myself to make a difference for others facing similar struggles.

What was so captivating about the talk on adult neurogenesis you attended in London, and how did it lead to a major shift in your research focus when you returned to Amsterdam?

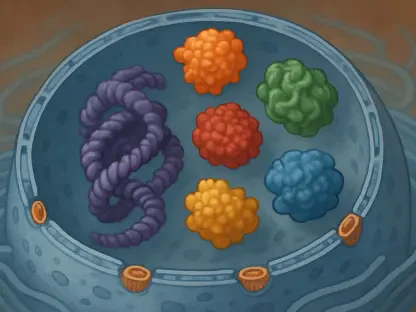

That talk in London was nothing short of a revelation—it turned my entire scientific worldview upside down. I almost missed it, booking a last-minute flight, but hearing about stem cells producing new neurons in adult brains was like lightning striking. The presenter’s passion, combined with the sheer audacity of challenging the long-held belief that brain cells couldn’t regenerate after childhood, left me buzzing with excitement as I sat in that dimly lit conference room. I knew instantly that my work on cell death was no longer enough; I had to pivot to studying cell birth. Back in Amsterdam, I gathered my team, and we threw ourselves into investigating adult neurogenesis, especially its ties to stress and depression. Those early days were chaotic—learning new techniques, designing experiments from scratch—but the thrill of possibly uncovering how the brain rebuilds itself kept us going. One of our first hurdles was simply proving these new cells existed in our models, and I’ll never forget the rush of seeing those initial results under the microscope; it felt like we were witnessing a hidden miracle of nature.

Can you tell us about your collaboration with the Eurogenesis consortium and share a standout discovery or project that emerged from working with other leading researchers in the field?

The Eurogenesis consortium was a game-changer for me, bringing together brilliant minds from across the globe to tackle adult neurogenesis as a team. These partnerships grew organically through conferences and shared interests—we were all obsessed with the same big questions about how new neurons form and what they mean for brain health. One of the most exciting outcomes was a project where we explored how neurogenesis might offer protection against neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s. It started with brainstorming sessions over late-night coffee at a workshop, scribbling ideas on napkins, and evolved into a rigorous series of experiments across labs. We found early evidence that stimulating neurogenesis could potentially slow cognitive decline in animal models, which was a heart-pounding moment when we first saw the data. I remember the shared joy in our group chat when the results came in—it felt like we were cracking open a door to new therapeutic possibilities. This collaboration reinforced my belief in team science; the insight we gained would’ve been impossible working alone, and it’s pushed my own research to focus more on translating these findings to human health.

Your recent work on early life programming and its connection to dementia resilience sounds incredibly promising. What inspired this focus, and can you walk us through a specific finding that highlights this relationship?

My interest in early life programming came from realizing that the brain’s adaptability—or plasticity—might be shaped long before we see symptoms of diseases like dementia. I started wondering how events in our earliest years, like stress or nurturing care, could program the brain for resilience or vulnerability later in life. This line of inquiry really took off when I saw how much early stress impacted brain structures in animal models, and I couldn’t help but think about human parallels. A key finding we published in 2025 showed that rodents exposed to early life stress had altered hippocampal plasticity, which correlated with memory deficits as they aged—mimicking patterns we see in dementia. In one experiment, we compared these stressed animals to a control group and noticed stark differences in neuron formation under a microscope; it was a somber moment, realizing how early adversity could cast such a long shadow. We’re now digging deeper into human brain tissue and data to see if these patterns hold, hoping to identify interventions that might boost resilience. Every time we uncover a piece of this puzzle, I feel a mix of urgency and hope—knowing we’re getting closer to protecting future generations.

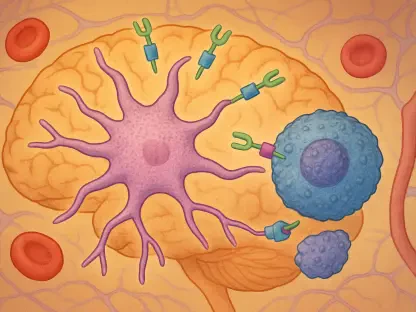

In the MODEM consortium, you’re using multi-omic approaches and machine learning in dementia research. How do these cutting-edge tools differ from traditional methods, and what unexpected insight have they revealed?

The MODEM consortium has been an incredible platform to push boundaries with multi-omic approaches, which basically means we’re looking at the brain through multiple layers—genomics, proteomics, and more—all at once, unlike traditional methods that often focus on one aspect at a time. Combining this with machine learning allows us to sift through massive datasets from rodent models and human postmortem brain tissue to spot patterns no human eye could catch. It’s a far cry from the days of manual data analysis I started with, where insights came slowly after months of painstaking work. One challenge has been integrating patient data with these algorithms; it’s tricky to account for all the variables in human life, and I’ve spent late nights troubleshooting models that just wouldn’t converge. But the payoff was worth it—recently, we uncovered an unexpected link between specific inflammatory markers and neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia patients. Seeing those results pop up on my screen after weeks of doubt was exhilarating; it felt like stumbling on a hidden clue. This has shifted how we think about inflammation’s role in brain disorders, opening up new avenues for targeted treatments.

Outside the lab, you’ve found balance through hobbies like comic art and cycling. How do these activities shape your scientific mindset, and can you recall a specific instance where stepping away led to a breakthrough?

Honestly, comic art and cycling are my lifelines—they pull me out of the intense, often narrow focus of research and let my mind wander in ways the lab doesn’t always allow. Flipping through graphic novels or admiring original artwork, I’m reminded of storytelling and creativity, which often sparks new ways to frame scientific questions. Cycling, on the other hand, is pure freedom; the rhythm of pedaling through Amsterdam’s streets clears the mental clutter. I vividly recall a moment a few years back when I was stuck on a particularly stubborn problem about stress and neurogenesis. I went for a long run, feeling the crisp air on my face, not thinking about work at all, and halfway through, an idea hit me about how to design a new experiment. I rushed home, jotted it down, and that spontaneous thought led to a key study design that shaped our understanding of recovery after stress. Stepping away like that taught me to trust my subconscious to process problems in the background—it’s become a deliberate part of my approach now.

You’ve spoken about systemic challenges in academia, like the glass ceiling for women and funding biases toward individual work. What barriers have you seen firsthand, and how do you work to address them in your role?

I’ve seen these challenges play out in real time, and they’re frustratingly persistent, especially in Dutch academia. For women, I’ve noticed how often they’re overlooked for leadership roles or struggle to secure funding despite stellar track records—I’ve watched brilliant female colleagues face subtle biases in grant reviews that their male counterparts rarely encounter. Funding systems also tend to reward individual “star” scientists rather than the collaborative, team-based efforts needed for big breakthroughs, which I’ve experienced when pitching consortium projects only to be told they’re “too complex.” I actively advocate for change by mentoring women in my group, ensuring their voices are heard in meetings, and pushing for their projects to get visibility. One specific moment that sticks with me was helping a talented female researcher secure a grant by co-writing the proposal late into the night; seeing her win that funding felt like a small victory against the system. I also prioritize team science in my group, often redistributing resources to support collaborative ideas, because I firmly believe that’s where the future of neuroscience lies.

Mentoring the next generation of scientists seems to bring you immense joy. What’s your philosophy on guiding young researchers in your Brain Plasticity group, and can you share a memorable moment of a student’s success that touched you deeply?

Mentoring is one of the most rewarding parts of my job—it’s like planting seeds and watching them grow into something incredible. My philosophy is to meet each student where they are, recognizing that everyone has unique strengths and needs. Some thrive on structure, so I map out detailed plans with them, while others need space to explore, so I encourage risk-taking with gentle guidance. I also try to foster a sense of curiosity and kindness, reminding them that science isn’t just about results but about the journey and the people you impact. One moment that stands out is with a PhD student who struggled with confidence early on; we worked closely for months, tweaking experiments and discussing ideas over countless coffees. When they finally presented their first major paper at a conference and received glowing feedback, I saw this spark of pride in their eyes—it hit me right in the heart. I felt like I’d not only helped them grow scientifically but also personally, and knowing they’ve since moved into a leading role in the field still fills me with pride every time I think about it.

Your mentors have clearly had a profound impact on your career. How did their approaches influence your own, and can you share a specific lesson from one of them that has guided you through a challenging research moment?

My mentors shaped me in ways I’m still discovering, each with their distinct style that left a lasting imprint. One taught me the value of relentless curiosity, always pushing me to ask the next question, while another showed me how humor and humanity can ground even the most intense scientific debates. Their energy and dedication, even after decades in the field, inspired me to keep my own passion alive no matter the setbacks. A specific lesson that stands out came during a particularly rough patch early in my career when a major project on stress and brain cells was failing, and I was ready to give up. This mentor sat me down and said, “Science isn’t about quick wins; it’s about staying curious even when the answers hide from you.” That advice echoed in my mind as I trudged back to the lab, reframed the experiments, and eventually uncovered a key insight about recovery after stress. Their words reminded me to embrace persistence and uncertainty, a mindset I carry into every challenge I face today.

As we wrap up, your work on brain plasticity connects so many critical areas like stress and disease. What’s one mechanism of brain adaptation that excites you most right now, and how do you envision it becoming a real-world therapy?

Right now, I’m incredibly excited about the role of adult neurogenesis in brain adaptation, particularly how it might help combat conditions like depression and dementia. The idea that we can stimulate the birth of new neurons to repair or protect brain circuits is mind-blowing—it’s like giving the brain a second chance to rebuild itself. In our lab, we’ve seen promising results in animal models where enhancing neurogenesis improves memory and mood regulation, and I can’t help but imagine the day this translates to humans. The journey from lab to clinic starts with identifying specific factors or drugs that boost this process safely, which we’re testing now through collaborations. Then, it’s about rigorous clinical trials to ensure efficacy and safety for patients—potentially developing therapies that could slow cognitive decline or lift the fog of depression. I envision a future where we personalize these treatments based on a person’s unique brain profile, and though it’s years away, every small step in the lab feels like we’re inching closer to changing lives. The hope of seeing a patient regain lost ground because of this work keeps me up at night—in the best possible way.

Looking ahead, what is your forecast for the future of brain plasticity research and its impact on treating neurological disorders?

I’m optimistic, yet cautiously so, about the future of brain plasticity research—it’s a field poised for transformative breakthroughs, but the complexity of the brain demands humility. I foresee us deepening our understanding of how plasticity interacts with lifestyle factors like nutrition and exercise, potentially leading to preventive strategies for disorders like dementia and depression. Advances in technology, like machine learning and multi-omic profiling, will likely accelerate our ability to map these mechanisms with unprecedented precision, revealing new therapeutic targets. I also believe we’ll see a shift toward personalized medicine, tailoring interventions to enhance plasticity based on individual profiles. However, the challenge will be translating these discoveries into accessible, affordable treatments while navigating ethical and systemic hurdles in healthcare. If we can foster more global collaboration and prioritize team science, I think in the next decade we’ll witness therapies that harness brain plasticity to not just treat, but potentially reverse aspects of neurological decline. That vision drives me every day, and I hope it inspires others to join this vital mission.