Within the intricate machinery of our cells, protein kinases serve as the master regulators, orchestrating a vast network of signals that control everything from cell growth to immune responses. They achieve this control through phosphorylation, the process of attaching a phosphate group to a target protein, effectively flipping a molecular switch. For years, a fundamental puzzle has perplexed biologists: how does a single kinase manage to add multiple phosphate groups to the same target in rapid succession without letting go? This highly efficient mechanism, known as processive phosphorylation, is essential for complex biological functions, but its underlying mechanics remained a mystery. Now, a groundbreaking discovery by researchers has illuminated this process by identifying a previously invisible, transient “hidden state,” a fleeting conformational shift that not only solves this long-standing puzzle but also opens an entirely new frontier for therapeutic intervention in diseases like cancer.

Unveiling a Molecular Quick-Change Artist

The primary challenge in processive phosphorylation lies in the need for both speed and precision. After a kinase transfers a phosphate group from adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to its target, it is left with a waste product, adenosine diphosphate (ADP), lodged in its active site. Before the next phosphorylation can occur, this ADP must be expelled and replaced with a fresh ATP molecule. This entire molecular exchange must happen in a fraction of a second, before the kinase detaches from its protein target. If the ADP release is too sluggish, the kinase will disengage, leaving the protein only partially phosphorylated and disrupting the intended biological signal. This delicate balance of binding, catalysis, and product release has been a significant bottleneck in understanding how kinases achieve the remarkable efficiency required to drive critical cellular processes like T-cell activation and cell migration, where multiple, rapid-fire phosphorylations are an absolute necessity for proper function.

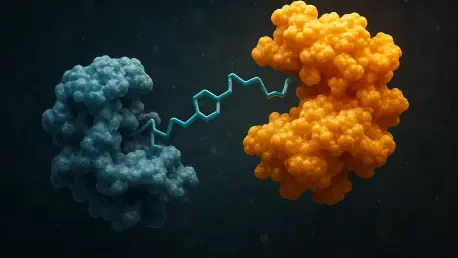

To probe the dynamic nature of these enzymes, researchers employed a powerful technique called nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, a method uniquely capable of detecting fleeting and low-population protein structures that are invisible to conventional imaging techniques. This advanced analysis revealed that Src family kinases adopt a previously unobserved “hidden” intermediate state. This transient conformation acts as a highly efficient ejection seat for the spent ADP molecule. By momentarily shifting into this specific shape, the kinase alters its active site, rapidly discarding the ADP and clearing the way for a new ATP molecule to bind almost instantaneously. This quick-release mechanism is the key that unlocks the secret to processive phosphorylation, allowing the kinase to remain securely docked on its target while rapidly cycling through the steps needed for repeated modifications. The discovery provides a definitive molecular explanation for how these enzymes achieve such high throughput without sacrificing accuracy.

From Discovery to Biological Importance

To validate the functional significance of this hidden state, the scientific team demonstrated its conservation across multiple members of the Src kinase family, including Lck and Hck, which are known to govern distinct cellular pathways. The fact that this mechanism is conserved strongly suggests it plays a vital and non-redundant role in biology. The team then took a more direct approach by introducing targeted mutations into the kinases, specifically designed to prevent them from adopting the hidden conformation. This effectively disabled the quick-release mechanism, and the biological consequences were profound. They observed that the migration of cells, a process critically dependent on the proper function of Src and Hck kinases, was severely impaired. More strikingly, the activation of T-cells, a cornerstone of the adaptive immune system regulated by the Lck kinase, was substantially compromised. These experiments provided direct evidence that the transient state is not merely a minor structural fluctuation but an essential component of a precise regulatory system that governs life-or-death cellular activities.

This work contributes to a significant paradigm shift in structural biology, reinforcing the understanding that proteins are not rigid, static entities but highly dynamic molecular machines. Their functions are often dictated by these fleeting, difficult-to-observe states that constitute a vast, unexplored landscape of biological regulation. The existence of such “invisible” states suggests that a whole new layer of cellular control has been operating just beyond the limits of previous detection methods. The research team anticipates that this discovery is only the beginning of a new chapter in understanding protein function. The plan is now to expand the search for similar hidden states in other kinase families and across the broader proteome. This line of inquiry promises to reveal many more of these invisible cogs in the cellular machine, providing deeper insights into the fundamental principles of life and uncovering new vulnerabilities in disease-causing proteins that can be targeted for therapeutic benefit.

Revolutionizing Therapeutic Strategies

The identification of this unique, transient structure has far-reaching implications for drug development, particularly in the fields of oncology and immunology. Kinases are among the most important drug targets, but many existing kinase inhibitors work by blocking the highly conserved ATP-binding site. Because this site is structurally similar across hundreds of different kinases, such drugs often cause significant off-target effects and toxicity, limiting their clinical utility. The hidden state, however, offers an entirely new strategy for therapeutic design. Since this state possesses a unique structure distinct from the common active or inactive conformations, it presents a novel target. Developing drugs that specifically bind to and either stabilize or disrupt this hidden state could allow for the modulation of kinase activity with unprecedented specificity. This approach could lead to the creation of a new generation of kinase-targeted therapies that are not only more effective but also significantly safer for patients.

The findings were particularly relevant for advancing cellular immunotherapies, such as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, a revolutionary treatment for certain cancers. The signaling machinery inside these engineered immune cells relies heavily on kinases like Lck to recognize and kill tumor cells. The discovery of the hidden state provided scientists with a new blueprint for fine-tuning the activity of these critical enzymes. By understanding the molecular mechanics of kinase activation in greater detail, it became possible to engineer CAR T-cells with enhanced signaling capabilities. This knowledge revealed new strategies to therapeutically alter kinase activity and modulate cell behavior, potentially boosting the cancer-killing efficacy and persistence of these powerful living drugs. The characterization of the hidden state ultimately provided a definitive explanation for a key biological process and simultaneously opened a promising new frontier for medicine.