A landmark investigation into the intestinal microbiome has uncovered a remarkably specific and nuanced connection to the progression of multiple sclerosis (MS), revolving around a deceptive cellular mechanism known as “molecular mimicry.” Collaborative research from the University of Basel and the University of Bonn has provided compelling evidence that certain gut bacteria, possessing surface structures that are nearly identical to the body’s own nerve tissues, can dangerously misdirect the immune system. This case of mistaken identity leads the body’s defenses to attack the central nervous system, thereby accelerating the advancement of this debilitating autoimmune disease. These pivotal findings, recently detailed in the journal Gut Microbes, not only illuminate a previously unclear pathway for disease progression but also paradoxically reveal promising new avenues for innovative treatments that could leverage the microbiome itself to induce immune tolerance and halt the devastating assault on the nervous system.

The Autoimmune Enigma

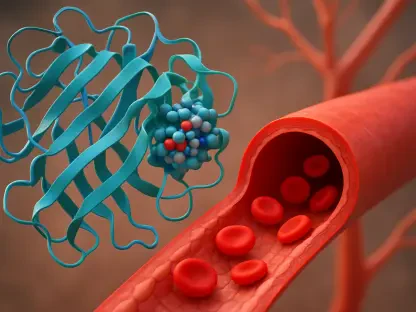

Multiple sclerosis is a chronic, often progressive autoimmune disorder in which the body’s own immune system erroneously targets and degrades the myelin sheath, the essential protective insulation that encases nerve fibers. The destruction of myelin disrupts the vital lines of communication between the brain and the rest of the body, leading to a spectrum of severe symptoms that can include profound exhaustion, numbness in the limbs, significant walking and mobility challenges, and, in its most advanced stages, paralysis. For decades, the scientific community has diligently investigated the precise triggers for this catastrophic immune system error. While the exact causes have remained elusive, a growing body of evidence has increasingly pointed toward the intestinal flora, or microbiome. This focus is supported by a consistent observation: the specific composition of gut microorganisms in individuals with MS is demonstrably different from that of healthy individuals, suggesting a deep, yet not fully understood, connection between the gut and the brain’s health.

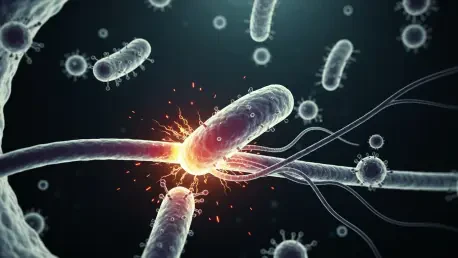

The core of this new research validates the long-theorized “molecular mimicry” hypothesis, which posits a fascinating and dangerous case of biological deception. According to this theory, certain pro-inflammatory bacteria that reside in the gut possess surface structures that bear a striking molecular resemblance to the body’s own myelin sheath. When the immune system correctly identifies these bacteria as a potential threat, it mounts a vigorous defensive response by creating and activating specialized immune cells to eliminate them. However, because of the profound structural similarity between the bacterial invader and the healthy nerve tissue, these activated immune cells become confused. They are unable to reliably distinguish between the foreign pathogen and the body’s own cells. As a direct result, the immune attack is directed not only at the harmful bacteria but also at the myelin sheath, initiating or dramatically exacerbating the destructive autoimmune assault that is the hallmark of multiple sclerosis.

From Hypothesis to Hard Evidence

To rigorously test this compelling hypothesis, the research team, led by Professor Anne-Katrin Pröbstel, designed a meticulously controlled experiment utilizing a genetically modified mouse model that effectively replicates the disease process of MS. Employing advanced molecular biological techniques, the scientists engineered two distinct types of bacteria. First, they modified a pro-inflammatory species, Salmonella, to express a surface structure deliberately designed to be molecularly similar to that of the myelin sheath. As a crucial control for the experiment, they used bacteria from the same Salmonella species but without this modified, self-like structure. When these engineered bacteria were introduced to the MS mouse models, the results were definitive and unambiguous. The mice that received the myelin-mimicking Salmonella experienced a markedly faster and significantly more severe progression of the disease compared to the mice that received the standard control bacteria. This outcome provided powerful, direct evidence that molecular mimicry acts as a potent accelerator of the disease.

Further analysis revealed that the mechanism driving the disease’s acceleration is a sophisticated two-part process. The presence of pro-inflammatory bacteria alone, it was found, only contributes to the disease to a limited extent. The critical factor that unleashes the full destructive potential is the powerful synergy that occurs between a pre-existing inflammatory environment within the gut and the specific trigger of molecular mimicry. This dangerous combination activates a very specific subset of immune cells, causing them to multiply at a rapid rate. These newly activated and programmed cells then migrate from the gut into the central nervous system. Once there, they launch a highly targeted and destructive attack directly on the myelin sheath, demonstrating a clear and direct pathway from a specific gut condition to neurological damage and highlighting the complexity of the gut-brain axis in autoimmune diseases.

A Paradigm Shift in Treatment Possibilities

In a pivotal second phase of the experiment, the research team investigated whether the fundamental nature of the bacteria—specifically, whether they were pro-inflammatory or non-inflammatory—altered the outcome. To explore this, they repeated the trials using E. coli bacteria, which are a common and generally benign part of the normal, healthy intestinal flora. They engineered these non-inflammatory E. coli bacteria to display the exact same myelin-like surface structure as the Salmonella in the first experiment. In stark and surprising contrast to the initial findings, when these modified E. coli were introduced into the mice, the progression of the MS-like disease was not accelerated. Instead, it was found to be significantly milder. This unexpected result suggested that the context in which the immune system encounters a self-like structure is critically important in determining its response.

This latter finding carries profound and exciting implications for the development of future therapeutic strategies for MS. It suggests that the immune response can be effectively modulated, or even reprogrammed, depending on the environment in which a self-like antigen is presented. Professor Pröbstel envisions a novel therapeutic strategy based on this principle, one that turns the mechanism of mimicry from a problem into a solution. The concept involves using different, specifically modified bacteria that actively calm the immune system instead of triggering it. By doing so, it might be possible to “train” immune cells to tolerate the myelin sheath and not attack it. This points toward the potential for creating sophisticated microbiome-based therapies that use engineered, non-inflammatory bacteria to educate the immune system, inducing a state of tolerance and ultimately halting the autoimmune attack at its source.

Broader Implications and Future Considerations

The overarching consensus from this comprehensive study was that the influence of the gut microbiome on multiple sclerosis is highly specific. It is not merely the overall composition or diversity of intestinal bacteria that matters, but rather the precise molecular details, such as the presence of myelin-like surface structures on particular bacterial species, that can play a direct and decisive role in both initiating and driving the disease’s progression. This insight moves the field beyond general observations about the microbiome’s health and toward a much more granular, molecule-focused understanding of how gut bacteria can directly impact neuroinflammation. It suggests that future diagnostic and therapeutic approaches must account for these specific molecular interactions rather than simply aiming to alter the gut flora in broad strokes, paving the way for more targeted and potentially more effective interventions for patients.

However, these findings also served as a crucial call for caution in other rapidly advancing areas of medicine. A potential unintended consequence was highlighted for certain cancer treatments that strategically utilize the microbiome. Some modern immunotherapies are designed to stimulate the immune system via the gut flora to more effectively combat tumors. This research suggested that while such a strategy could be highly beneficial for fighting cancer, it might also create a highly inflammatory environment in the intestine. In this heightened state of immune activity, the presence of any bacteria exhibiting molecular mimicry could inadvertently trigger or worsen autoimmune reactions or diseases in susceptible patients. This underscored the delicate and intricate balance of the immune system and its complex relationship with our microbiome, reminding the medical community that manipulating one part of this system can have profound and unforeseen effects on another.