A groundbreaking study led by researchers from The University of Texas at Austin and Harvard Medical School has challenged the prevailing assumption that infants exposed to gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) are at an automatically higher risk of developing childhood obesity. Published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, this research presents compelling evidence suggesting that these infants may experience slower fat gain over their first year of life. This novel finding implies that the early growth patterns of GDM-exposed infants are more adaptable and capable of self-correction than previously understood, thereby dispelling long-held notions about their susceptibility to obesity.

Understanding Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM)

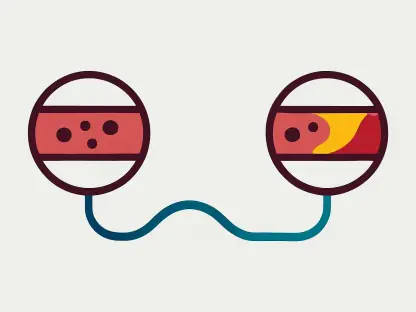

Gestational diabetes mellitus, commonly referred to as GDM, is a significant medical condition affecting approximately 8.3% of pregnancies in the United States, a figure that has seen a considerable rise over the past two decades. This condition poses heightened risks for pregnancy complications, such as preeclampsia and cesarean delivery, and also increases the likelihood of Type 2 diabetes later in life for mothers. Traditionally, it has been acknowledged that infants born to mothers with GDM tend to exhibit higher birth weights, greater adipose tissue amounts, and elevated body mass indices (BMIs), all of which have been associated with an increased risk of developing obesity and Type 2 diabetes as they mature.

The backdrop of this new study is rooted in these established beliefs, highlighting the importance of closely examining the early growth patterns of infants exposed to GDM. Previous research has broadly indicated that GDM-exposed infants are more prone to adverse health outcomes as they age. By investigating these patterns during the critical first year of life, the study aims to provide a more detailed understanding that could ultimately shift the narrative around GDM and infant health.

Study Design and Methodology

The research involved meticulously tracking the development of 198 infants, half of whom were exposed to GDM in utero, with data spanning a decade from 1996 to 2006. This period precedes the widespread use of medications like metformin or insulin for managing blood sugar levels in GDM, offering a unique perspective on natural growth trajectories. Researchers collected comprehensive measurements of each infant’s weight, length, and body fat at birth and multiple intervals during the first 12 months, employing advanced statistical methods to distinguish three distinct growth trajectories.

This rigorous approach enabled a granular analysis of infant growth patterns, focusing not just on overall weight but on specific components such as fat mass and lean body mass. Using this methodology, the study sought to uncover any significant differences between GDM-exposed and non-GDM-exposed infants, thereby providing a deeper understanding of how GDM impacts early development.

Surprising Findings: Slower Fat Gain

Contrary to expectations, the study’s results revealed that infants exposed to GDM exhibited slower fat gain while showing an equivalent increase in lean body mass compared to their non-GDM counterparts. This phenomenon, known as “catch-down growth,” is typically seen in heavier babies who gradually align with typical growth patterns over time. Corresponding author Elizabeth Widen, an assistant professor of nutritional sciences at UT Austin, emphasized that while these infants may initially have more body fat, many naturally balance out as they grow, contributing to a more complex understanding of their growth trajectory than previously assumed.

The significance of these findings lies in their ability to shift the focus from a simplistic view of GDM-exposed infants being irrevocably predisposed to obesity to a more nuanced perspective acknowledging their potential for adaptive growth. By recognizing that many of these infants engage in physical growth adjustments that align with healthier patterns over time, the study challenges conventional wisdom and opens the door for more individualized monitoring and intervention strategies.

Implications for Childhood Obesity Risk

Further analysis of the data determined that GDM-exposed infants were more likely to experience slower growth in fat mass and body fat percentage. These infants showed a higher propensity to fall into groups characterized by the slowest BMI growth or even a decrease in BMI, providing a stark contrast to prior assumptions about their increased risk of childhood obesity. Harvard Medical School professor Patrick Catalano, who oversaw the study’s data collection, pointed out that these findings are consistent with previous research from the Maternal Fetal Medicine Units Network. Their studies had indicated that treating mild GDM during pregnancy did not substantively impact childhood obesity or metabolic outcomes in offspring aged 5 to 10 compared to control groups.

This insight underscores the necessity for reevaluating established practices in managing GDM pregnancies and monitoring infant growth. If interventions aimed at mitigating GDM’s impact do not significantly alter long-term health outcomes, it suggests that other factors may play a critical role in the early development of these infants. Policymakers and healthcare professionals may need to consider alternative strategies focused on supporting natural growth processes rather than solely relying on medical treatments during pregnancy.

Detailed Examination of Early Growth Patterns

Lead author Rachel Rickman, formerly a doctoral student under Widen, highlighted that previous studies lacked the precision in measuring body fat during the first year of life employed in this research. The study presents striking data that provoke further questions about the growth patterns of GDM-exposed infants. Contributions from co-authors Marcela R. Abrego and Saralyn F. Foster of UT Austin, Amy R. Nichols of the University of California, Davis, and Charlotte E. Lane of Food Security Evidence Brokerage, alongside funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the General Clinical Research Center, underscored the collaborative effort behind this groundbreaking research.

The detailed examination of body composition and growth trajectories offered by this study provides a nuanced lens through which to view early-life development. By delving into specific metrics such as fat percentage and lean body mass growth, the researchers have paved the way for more targeted and effective monitoring strategies for infants exposed to GDM, thereby enhancing the potential for healthier long-term outcomes.

Rethinking Infant Growth Monitoring

In conclusion, this study challenges the traditional view that GDM-exposed infants are fated to an increased risk of childhood obesity. Instead, it points to their growth patterns being not only adaptable but also subject to self-correction during their first year of life. These findings suggest that enhanced monitoring protocols could be designed to support healthier growth trajectories for GDM-exposed infants, potentially mitigating long-term health risks. The research underscores the importance of a nuanced understanding of early development, which could lead to more personalized interventions and improved outcomes for affected infants.

Future Research Directions

A pioneering study headed by researchers from The University of Texas at Austin and Harvard Medical School has put into question the common belief that infants exposed to gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) are automatically at a higher risk of developing childhood obesity. This research, published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, offers compelling evidence indicating these infants might actually experience slower fat accumulation in their first year of life. This new discovery suggests that the early growth trajectories of GDM-exposed infants are more adaptable and capable of self-regulation than previously thought. The findings challenge long-standing viewpoints about the vulnerability of these infants to obesity. Beyond changing our understanding of early growth patterns in GDM-exposed infants, the study may also influence future healthcare guidelines and recommendations for managing and monitoring these children’s growth and health. This reinforces the importance of revisiting and updating medical assumptions based on emerging scientific evidence.