A state-of-the-art biologic drug, meticulously designed to fight a specific disease and carrying a price tag that can exceed several hundred thousand dollars, inexplicably fails in a patient who seemed a perfect candidate for the treatment. This frustrating scenario, long a puzzle for clinicians, is now being explained by a subtle saboteur hidden within our own DNA. Groundbreaking research reveals that common, naturally occurring genetic variations can render some of the most powerful antibody therapies completely ineffective, a discovery that challenges the foundations of personalized medicine and calls for a new approach to treatment selection.

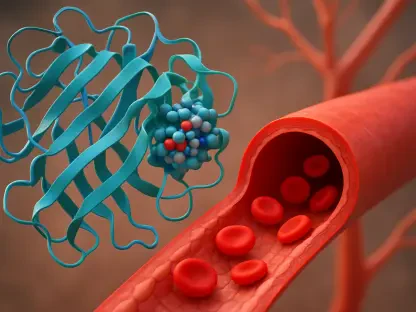

These highly specific therapies, which form the bedrock of treatment for diseases from cancer to multiple sclerosis, are engineered to function like a molecular key, binding to a precise location—an epitope—on a target protein to neutralize or destroy diseased cells. This lock-and-key precision is their greatest strength, but it is also their Achilles’ heel. The recent findings demonstrate that if a person’s genetic code contains even a minor variation that alters a single amino acid in that target epitope, the “lock” is effectively changed. The therapeutic antibody “key” no longer fits, the treatment cannot bind, and the patient receives no benefit, all because of a tiny, otherwise harmless quirk in their genome.

When the Key No Longer Fits the Lock

The mechanism behind this therapeutic failure is rooted in the fundamental principles of biochemistry. Therapeutic antibodies are large, complex proteins designed to recognize and attach to a specific molecular shape on another protein, much like a puzzle piece fits perfectly into its designated spot. This binding action is what triggers the drug’s intended effect, whether it is blocking a signaling pathway that fuels cancer growth or marking an invasive cell for destruction by the immune system. The specificity of this interaction is absolute; the antibody is programmed to ignore millions of other proteins in the body and target only one.

However, the genetic blueprint for every protein in the body is not uniform across the human population. Minor differences, known as genetic variants, can lead to slight changes in the amino acid sequence of a protein. When such a variation occurs at the exact site where a therapeutic antibody is designed to dock, it disrupts the precise molecular interaction required for binding. This single-point failure transforms the target protein into an unrecognizable shape from the antibody’s perspective, neutralizing the drug before it can ever perform its function. The patient’s own genetic makeup, therefore, becomes an unintentional barrier to treatment.

Uncovering a Hidden Genetic Sabotage

What was once considered a rare phenomenon is now understood to be a widespread issue. A comprehensive study led by researchers at the University of Basel systematically scanned the genomes of thousands of individuals, cross-referencing them with the known binding sites of 87 different therapeutic antibodies. The results were startling, revealing what the researchers described as an “astonishingly large number” of genetic variants located directly within these critical docking sites. This suggests that for any given antibody therapy, a portion of the population carries a genetic profile that predisposes them to treatment resistance.

A crucial insight from this research is that these genetic variations are not pathogenic mutations; they do not cause disease and, in most circumstances, have no discernible impact on a person’s health. The proteins they encode function normally within the body. Their clinical significance only emerges when a patient is administered a highly specific antibody drug designed to target the very protein that their DNA has subtly altered. These variants are silent saboteurs, lurking harmlessly in the genome until a specific medical intervention unwittingly turns them into a mechanism of therapeutic failure.

From Digital Prediction to Laboratory Proof

To confirm their computational findings, the research team transitioned from bioinformatic analysis to empirical lab work. They began by using sophisticated computer models to predict which of the identified amino acid variants were most likely to interfere with antibody binding. This digital screening allowed them to narrow down the vast number of variants to a handful of high-probability candidates for further investigation. The models simulated the molecular interactions between the antibody and the altered protein, flagging variants that would physically obstruct or weaken the connection.

These predictions were then rigorously tested in the laboratory on four medically important proteins and their corresponding antibody therapies. The experiments provided definitive proof of the theory. For each of the proteins studied, the researchers confirmed that specific, naturally occurring genetic variants completely prevented a therapeutic antibody from binding to its target. This validation moved the concept of genetic resistance from a theoretical possibility to a demonstrated biological reality, providing a concrete explanation for why some patients do not respond to treatments that are effective for others.

A Strategic Path to Overcoming Resistance

While confirming the problem, the laboratory experiments also illuminated a clear path toward a solution. The research team made a critical observation: when one antibody was blocked by a genetic variant, an alternative antibody designed to target a different epitope on the same protein could often bind successfully. This finding is profoundly important for clinical practice, as it suggests that resistance is not necessarily a dead end. Instead, it points to a strategic pivot in treatment.

This principle establishes a framework for overcoming genetically-driven resistance. If a patient fails to respond to a particular antibody therapy, the cause may not be the progression of their disease but a specific genetic mismatch. By identifying the variant through genetic testing, clinicians could potentially switch to a different biologic drug that targets an unaffected region of the same protein. This approach would allow for the continuation of a targeted therapeutic strategy, tailored not only to the disease but also to the patient’s unique genetic profile.

The Case for a New Standard of Care

These findings present a compelling argument for integrating preemptive genetic screening into routine clinical practice. As Professor Lukas Jeker, a leader of the study, noted, clinicians should consider genetics when a therapy unexpectedly fails. For exceptionally expensive treatments, such as CAR T-cell therapies in oncology, the economic case is even stronger. Co-author Dr. Romina Marone argued that the cost of a simple genetic test is minuscule compared to the immense expense of administering a powerful therapy that is destined to fail, not to mention the unnecessary side effects and emotional toll on the patient.

The implications extend deep into the drug development pipeline. Dr. Rosalba Lepore, the study’s first author, recommended that participants in clinical trials undergo genetic screening for the relevant binding sites before enrollment. This would ensure that the study population is suitable for the drug being tested, preventing skewed results where non-responders are included due to unknown genetic resistance. Such a measure would lead to more accurate data on a drug’s true efficacy and could accelerate the approval of effective new medicines.

This research has also cast a harsh light on a significant issue of global health equity. The frequency of these treatment-altering variants differs across global populations. A variant that is rare in people of European descent might be common in Asian or African populations, yet genomic databases are overwhelmingly skewed toward the former. This data gap means that variants relevant to large portions of the world’s population may remain unknown, leading to unexplained treatment failures and exacerbating existing health disparities. The study ultimately underscored that for personalized medicine to fulfill its promise, its foundation must be built upon genomic data that represents all of humanity.