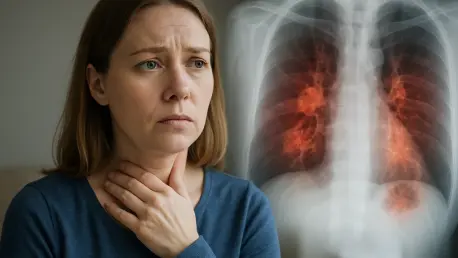

With the landscape of lung cancer shifting dramatically, we’re seeing a concerning rise in cases among people who have never smoked. This group, once considered low-risk, now represents a significant and growing portion of diagnoses, revealing a distinct form of the disease that challenges our traditional approaches. To shed light on this urgent issue, we’re joined by Biopharma expert Ivan Kairatov, whose work in research and development provides a unique perspective on the future of oncology. We will explore the critical need for new diagnostic strategies that look beyond smoking history, the complexities of tailoring treatments for this specific patient population, and the innovative public health measures required to protect a new generation from this devastating illness.

Given that a young, non-smoker with shoulder pain might not be immediately assessed for lung cancer, what specific steps can primary care physicians take to overcome this diagnostic bias? Please walk us through a more effective clinical approach for these patients.

This is the central challenge we face, as it strikes at the heart of our clinical intuition. For decades, the image of a lung cancer patient has been inextricably linked to a long history of smoking. The first step for physicians is a conscious mental reset. When a young, non-smoking patient presents with persistent, unexplained symptoms—be it shoulder pain, a nagging cough, or shortness of breath—we must broaden our diagnostic lens. Instead of defaulting to more common explanations, physicians should incorporate a “what if” a roach that includes cancer. This means developing a higher index of suspicion and utilizing low-dose CT scans more readily when symptoms don’t resolve. We need to move beyond a simple smoking history questionnaire and build a more holistic risk profile that considers family history and environmental exposures, even if they seem minor. It’s about shifting from a reactive to a proactive mindset to catch these cases before they advance.

Current screening is overwhelmingly geared toward smokers. How can we transition to a risk-based model that incorporates factors like genetics, radon, and air pollution exposure? Describe the primary challenges and what a successful rollout of this new approach might look like in practice.

Transitioning to a comprehensive risk-based model is our most logical and necessary next step, but it’s fraught with challenges. The primary obstacle is data integration and validation. Unlike smoking, which is a powerful and singular risk factor, factors like radon, air pollution, and genetics have more modest individual impacts. We need to develop and validate algorithms that can weigh these diverse inputs accurately to identify a truly high-risk individual. A successful rollout would look like this: a patient’s electronic health record would automatically flag them for a discussion about screening based not just on age and smoking, but also on their residential history for radon exposure, their genetic predispositions, and even data on local air quality. This would trigger a conversation with their doctor, leading to a personalized screening plan. It’s a move from a one-size-fits-all approach to a truly bespoke preventive strategy.

We understand that immunotherapy is less effective for never-smokers, while therapies targeting specific genetic mutations are more promising. Can you elaborate on the biological reasons for this difference and share an example of how identifying a mutation directly shapes a patient’s treatment journey?

The biological divergence is fascinating and is rooted in how the cancer originates. Smoking-related cancers are born from a constant barrage of carcinogens, leading to thousands of mutations. This high mutational burden creates a chaotic cellular environment that makes the cancer cells look very “foreign” to the immune system, giving immunotherapy a clear target to attack. In contrast, lung cancer in a never-smoker often arises from a single, potent genetic driver—one critical switch that goes haywire. Since there are fewer mutations, the cancer doesn’t trigger the same strong immune response, rendering immunotherapy less effective. However, this “single switch” is also its Achilles’ heel. For example, if we identify an EGFR mutation, which is common in this group, we can prescribe a targeted therapy like a tyrosine kinase inhibitor. This drug specifically blocks the faulty EGFR signal, effectively shutting the cancer down at its source. For that patient, the discovery of that one mutation completely transforms their prognosis and treatment path from broad chemotherapy to a highly precise and often more tolerable oral medication.

The link between clonal hematopoiesis and lung cancer risk is an emerging field. What are the practical first steps for integrating screening for this inflammatory condition into cancer prevention, and what specific anti-inflammatory strategies are being explored for high-risk individuals?

This is an exciting frontier because it connects the dots between aging, inflammation, and cancer risk, irrespective of smoking. The first practical step is to make screening for clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential, or CHIP, more routine, especially in older populations. This can be done through simple, sophisticated blood tests that are already becoming more accessible. Once we identify an individual with CHIP, we know they are in a state of chronic, low-grade inflammation that can fuel tumor growth. For these high-risk individuals, we’re actively exploring targeted anti-inflammatory strategies. This isn’t just about taking a daily aspirin; we’re looking at more specific pathways. Clinical trials are investigating drugs that can dampen the inflammatory signals driven by these abnormal blood stem cells, potentially intercepting the cancer-promoting process before a tumor ever has the chance to form. It’s a true form of pre-cancer prevention.

Public health measures like radon monitoring and reducing pollution are critical for prevention. From your perspective, where should we focus our resources for the greatest impact, and can you detail a successful community-level program that has effectively mitigated these environmental risks?

For the greatest impact, our resources must be focused on awareness and action at the local level, because environmental risks are often zip-code dependent. Radon is a perfect example. It’s a silent, invisible threat lurking in people’s homes. A highly successful community-level approach involves partnering with local governments and real estate agencies to make radon testing a standard part of home inspections and sales. Public health departments can offer subsidized testing kits and educational workshops, empowering homeowners to identify and mitigate high radon levels with simple ventilation systems. Similarly, for air pollution, programs that create low-emission zones in city centers or provide real-time air quality alerts via mobile apps allow citizens to make informed decisions to protect their health. These aren’t abstract national policies; they are tangible, community-driven initiatives that directly reduce exposure and, ultimately, save lives.

What is your forecast for the future of diagnosing and treating lung cancer in people who have never smoked?

My forecast is one of cautious optimism, driven by a profound shift toward personalization. In the next decade, the diagnosis of “lung cancer in a never-smoker” will become an obsolete, overly broad term. Instead, a diagnosis will be defined by its specific molecular signature—an “EGFR-mutant lung cancer” or a “ROS1-positive lung cancer.” We will move beyond tissue biopsies and rely on simple blood tests, or liquid biopsies, to detect cancer DNA circulating in the bloodstream, allowing for much earlier detection and monitoring. Treatment will be a dynamic process, with therapies adjusted in real-time based on the cancer’s evolving genetic makeup. We will have a robust arsenal of targeted drugs and innovative strategies to combat resistance, turning a once-fatal diagnosis into a manageable, chronic condition for many. The future is precise, predictive, and proactive.