The conversation surrounding alcohol’s impact on health has taken a dramatic turn with emerging research that questions long-held beliefs about its safety, particularly when it comes to brain health, and a recent study published in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine has stirred significant debate by suggesting that even moderate alcohol consumption might elevate the risk of dementia, a devastating condition characterized by progressive cognitive decline. For decades, the public has been guided by the notion that light drinking could offer protective benefits against such neurodegenerative diseases, a perspective rooted in earlier observational data. However, this new evidence challenges that narrative, raising critical questions about whether any level of alcohol intake is truly safe for the brain. By delving into innovative methodologies and expansive datasets, the study provides a fresh lens through which to view this pressing public health issue. This article examines the evolving science, historical assumptions, and potential implications for how society approaches alcohol consumption in relation to cognitive well-being.

Revisiting Past Assumptions About Alcohol and Brain Health

The historical perspective on alcohol and dementia risk has often leaned on a “U-shaped” curve, a pattern derived from older observational studies indicating that light to moderate drinking—typically fewer than seven drinks per week—might lower the likelihood of cognitive decline compared to abstaining entirely or consuming heavily. This concept gained traction over the years, influencing public health recommendations and fostering a belief that a glass of wine or beer could be beneficial for the brain. Yet, this latest research uncovers significant flaws in those earlier conclusions, pointing to confounding variables such as lifestyle differences or the conflation of lifelong non-drinkers with individuals who ceased drinking due to pre-existing health concerns. Such factors likely distorted the perceived protective effect, painting an overly optimistic picture of moderate alcohol use. As a result, the foundation of past guidelines is now under scrutiny, prompting a reevaluation of what constitutes safe consumption when it comes to preserving mental acuity over time.

Moreover, the implications of these historical missteps are profound, as they have shaped not only individual behaviors but also broader societal attitudes toward drinking. The assumption of a safe threshold for alcohol intake may have led many to underestimate potential risks, particularly for long-term brain health. The new study emphasizes that observational data alone cannot account for hidden biases, such as the possibility that some non-drinkers in past research were already experiencing early, undiagnosed cognitive issues, skewing risk comparisons. This revelation calls for a shift in focus toward more robust scientific approaches that can better isolate alcohol’s direct impact. By acknowledging these limitations, the research community is paving the way for a more accurate understanding of how even small amounts of alcohol might contribute to neurodegenerative outcomes, urging a cautious reconsideration of long-standing public health messaging around moderate drinking.

Cutting-Edge Approaches to Uncover Causal Links

One of the standout features of the recent study is its adoption of Mendelian randomization, a sophisticated genetic technique that leverages natural variations in DNA to simulate lifelong alcohol exposure patterns. Unlike traditional epidemiological methods that depend heavily on self-reported data—often clouded by personal biases or environmental factors—this approach offers a clearer path to establishing causality between alcohol consumption and dementia risk. By using genetic markers as proxies for drinking behavior, the study minimizes the noise of external influences, providing a more reliable assessment of how alcohol directly affects cognitive health. This innovative methodology represents a significant leap forward in medical research, offering insights that challenge conventional wisdom and highlight the potential dangers lurking even in moderate intake levels.

Additionally, the integration of this genetic analysis with vast observational datasets creates a comprehensive framework for understanding alcohol’s impact on the brain. The study draws from over half a million participants, ensuring a broad and diverse sample that enhances the credibility of its conclusions. This dual approach reveals a stark contrast between past assumptions and current evidence, with genetic findings indicating a linear increase in dementia risk as alcohol consumption rises, even minimally. Such results underscore the importance of moving beyond surface-level data to uncover deeper truths about health risks. As this methodology gains prominence, it could reshape how future studies address complex relationships between lifestyle factors and chronic conditions, potentially influencing a wide range of public health policies aimed at safeguarding cognitive function across aging populations.

Broad Scope and Long-Term Insights From Diverse Populations

The sheer scale of the research is another critical element that bolsters its significance, as it encompasses data from over half a million individuals across the US Million Veteran Program and the UK Biobank. Participants, ranging in age from 56 to 72 at the study’s outset, represent a mix of European, African, and Latin American descent, offering a cross-section of demographic diversity rarely seen in prior investigations. Tracked for up to 12 years, this longitudinal design captures the gradual progression of dementia risk over a substantial period, lending weight to the findings’ applicability across varied groups. Such an extensive and inclusive approach ensures that the results are not narrowly confined to a single population, providing a more universal perspective on how alcohol consumption might influence cognitive decline over time in different contexts.

Beyond its diversity, the long-term nature of the study sheds light on the cumulative effects of alcohol exposure as individuals age, a factor often overlooked in shorter-term analyses. This extended follow-up period reveals patterns that might otherwise remain hidden, such as the slow buildup of neurotoxic damage that could precede diagnosable dementia by years. While the genetic data offers a compelling case for causality, the observational component still shows discrepancies, like higher risks among non-drinkers, which may reflect underlying biases rather than true protective effects of drinking. These nuances highlight the value of sustained research efforts that account for both immediate and delayed health outcomes. As such, the study’s design sets a high standard for future explorations into chronic disease risk factors, emphasizing the need for patience and precision in unraveling the intricate ties between lifestyle choices and long-term well-being.

Emerging Evidence of Alcohol’s Neurotoxic Effects

Contrary to earlier beliefs that moderate drinking might shield against dementia, the genetic analysis from this study paints a sobering picture, revealing a dose-dependent relationship where even an additional one to three drinks per week correlates with a 15% higher risk of cognitive decline. This finding directly contradicts the once-popular “U-shaped” model, aligning instead with a growing body of evidence that points to alcohol’s harmful effects on the brain, including oxidative stress and vascular impairment. These mechanisms can erode neural integrity over time, diminishing the brain’s capacity to withstand age-related deterioration. As this linear risk pattern emerges, it becomes increasingly clear that the notion of a safe drinking threshold for brain health may be a myth, prompting an urgent need to reassess how alcohol’s risks are communicated to the public.

Furthermore, the shift in scientific consensus toward recognizing alcohol as a neurotoxin carries significant weight for both individual decision-making and broader health initiatives. The study’s genetic evidence bypasses many of the pitfalls of observational research, offering a stark warning that no level of consumption appears free from potential harm when it comes to dementia risk. This perspective is reinforced by comparisons with heavy drinkers, who face even steeper increases in risk, yet the incremental danger from light intake remains a critical takeaway. Such insights challenge policymakers and health advocates to prioritize education on alcohol’s long-term consequences, moving away from outdated narratives of moderation as a protective strategy. As research continues to evolve, these findings could serve as a catalyst for more stringent guidelines aimed at minimizing cognitive health risks across all levels of alcohol use.

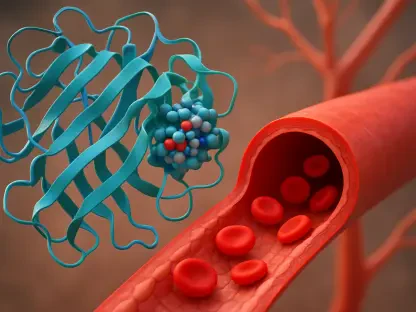

Understanding the Biological Toll on Cognitive Reserve

Delving into the mechanisms behind alcohol’s impact, the research highlights how it can inflict direct toxicity on neurons while also disrupting vascular health, both of which undermine the brain’s cognitive reserve—the protective buffer against decline. These biological pathways explain why even small amounts of alcohol might contribute to long-term damage, as repeated exposure can trigger inflammation and oxidative stress that harm neural connections over decades. While observational data in the study still suggests that non-drinkers and heavy drinkers face elevated risks compared to light drinkers, the genetic evidence counters this, pointing to biases like reverse causation, where early dementia symptoms might prompt reduced drinking before a diagnosis is made. This complexity underscores the challenge of interpreting alcohol’s effects without advanced tools to separate cause from correlation.

Equally important is the implication of these biological insights for public health strategies moving forward. Recognizing that alcohol can erode the brain’s resilience suggests that preventive measures should focus on minimizing exposure at all stages of life, rather than endorsing any level as safe. The study’s emphasis on vascular damage also ties alcohol consumption to broader cardiovascular risks, which are themselves linked to dementia, creating a compounded threat. Addressing this requires a holistic approach that integrates brain health into wider wellness campaigns, encouraging reduced alcohol intake alongside other protective habits like diet and exercise. As science uncovers more about these destructive processes, there is a growing responsibility to translate such knowledge into actionable advice, ensuring that individuals are equipped to make informed choices about their drinking habits in the context of preserving mental sharpness.

Reflecting on a Paradigm Shift in Health Guidance

Looking back, the journey from accepting moderate drinking as potentially beneficial to recognizing its risks marks a pivotal moment in public health discourse. The groundbreaking study in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine shifted the narrative by demonstrating through genetic analysis that even light alcohol consumption heightened dementia risk, a stark departure from past observational trends. Its comprehensive approach, blending diverse participant data with innovative methodologies, provided a clearer lens on alcohol’s neurotoxic potential. Moving forward, the focus should pivot to actionable steps, such as updating health guidelines to reflect these findings and prioritizing education on the cumulative dangers of drinking. Further research must also address gaps in demographic representation to ensure universal applicability. By fostering a dialogue around safer lifestyle choices and supporting policies that minimize alcohol exposure, society can better safeguard cognitive health for future generations.