With us today is a leading expert in biopharmaceutical innovation, here to break down a remarkable new development in diagnostic technology. We’ll be exploring a novel biosensor test strip that promises to detect disease markers with unprecedented sensitivity, potentially moving complex diagnostics out of the lab and into the hands of non-specialists. Our conversation will touch on the clever enzyme-based mechanics that make this possible, how it stacks up against traditional methods like PCR, and the practical challenges of bringing such a revolutionary tool to the wider world.

This new biosensor reportedly detects microRNAs at concentrations a trillion times lower than glucose. Could you walk us through how the enzyme boosts the electrical signal to achieve this sensitivity, and what were the main hurdles in making this process work on a simple test strip?

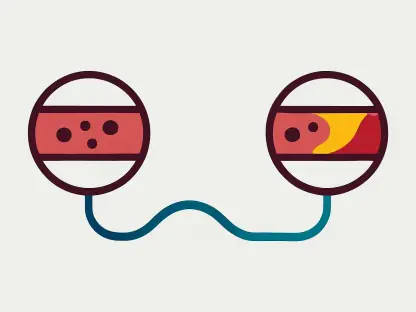

It’s an absolutely fascinating piece of electrochemical engineering. Think of a standard glucose strip—it measures a relatively abundant molecule. Here, we’re hunting for microRNAs, which are like finding a few specific grains of sand on a vast beach. The core challenge is making that tiny presence generate a detectable signal. The breakthrough was incorporating a specialized enzyme. When the target microRNA is present in a blood or plasma sample, it triggers a reaction on the strip that causes the baseline electrical signal to drop. The enzyme acts as a powerful amplifier for this specific event. It dramatically magnifies that small decrease in the signal, making it measurable. This amplification is so effective that it allows detection at concentrations 1000 times lower than without it, reaching that astonishing sensitivity level. The main hurdle was stabilizing this complex enzymatic reaction on a disposable, single-use strip while ensuring it remained reliable and didn’t produce false positives.

Detecting microRNAs with standard lab methods like PCR can be challenging due to their low concentrations. How does this new biosensor’s approach differ from PCR in detecting these tiny molecules, and what are the key practical advantages for clinicians regarding speed, cost, and ease of use?

The difference is truly night and day, and it really comes down to simplicity and immediacy. PCR, or Polymerase Chain Reaction, is the gold standard for a reason—it’s incredibly sensitive. However, it requires a laboratory, expensive thermal cycling equipment, and highly trained technicians to run the process, which involves amplifying the genetic material over several hours. This biosensor sidesteps that entire infrastructure. It’s a direct electrochemical detection method. You apply the sample, and the enzyme-amplified reaction gives you a result right there. For a clinician, this means no more sending samples off to a centralized lab and waiting days for a result. The potential is for a test that is not only faster but also significantly cheaper per unit, as it eliminates the need for complex reagents and machinery. This accessibility could be transformative for early-stage screening and monitoring diseases like cancer.

The vision for this technology is a point-of-need device that non-specialists can use. What key design elements are needed to make it truly affordable and effective for use outside a lab, and what are the biggest regulatory hurdles for bringing such a tool to market?

To truly realize that point-of-need vision, the design must prioritize radical simplicity and affordability. The test strips themselves need to be mass-producible, similar to glucose strips, to keep costs down. The accompanying reader device must be portable, battery-powered, and have an intuitive interface—think a simple “positive” or “negative” display, or a clear numerical readout that requires no interpretation. It must be robust enough to work reliably in various environments, not just a pristine clinic. On the regulatory front, the biggest hurdle is proving its accuracy and reliability are on par with existing, approved laboratory methods. Regulatory bodies will demand extensive clinical trial data demonstrating that it has high sensitivity and specificity—meaning it correctly identifies those with the disease marker and correctly clears those without it. Gaining that approval is a long, expensive road, but it’s essential for a diagnostic tool that will guide real-world medical decisions.

The test strip operates by decreasing its electrical signal when microRNA is present. Can you explain the electrochemical reaction that causes this signal drop and why amplifying this specific change is a more effective detection method than other potential approaches you considered?

The elegance of the system is in its “signal-off” mechanism. The surface of the test strip is engineered to produce a steady, baseline electrical current. When the sample is introduced, the target microRNA molecules bind to probes on the strip’s surface. This binding event interferes with the flow of electrons to the electrode, causing the electrical signal to drop. The more microRNA that binds, the more significant the drop. Now, this initial signal change is minuscule. This is where the enzyme’s brilliance comes in. The enzyme is designed to specifically recognize these bound microRNA duplexes and amplifies the signal-blocking effect enormously. Choosing to amplify this decrease, rather than trying to generate a new signal, is often more stable and less prone to background noise. It creates a clearer, more distinct result, which is precisely what you need when you’re detecting molecules at attomolar concentrations—that’s one part in a quintillion, an almost unimaginably small amount.

What is your forecast for the field of point-of-need biosensors over the next decade?

I believe we are on the cusp of a healthcare revolution driven by these technologies. Over the next ten years, I forecast a dramatic shift from centralized lab testing to decentralized, point-of-need diagnostics for a wide range of conditions beyond just cancer. We will see these biosensors integrated into smart, user-friendly devices for monitoring chronic illnesses, detecting infectious diseases in remote communities, and providing rapid feedback for personalized medicine. The key will be advancements in multiplexing—the ability for a single strip to test for multiple microRNAs or other biomarkers simultaneously, giving a more complete diagnostic picture from a single drop of blood. The challenge will be data management and ensuring regulatory frameworks can keep pace with the speed of innovation, but the destination is clear: a future where powerful diagnostic information is accessible, affordable, and available to anyone, anywhere, at any time.