The relentless global rise of hypertension has long been shadowed by its close companion, obesity, creating a public health crisis that has puzzled scientists and clinicians for decades. For years, the prevailing wisdom held that the sheer volume of body fat was the primary driver of high blood pressure, a simple equation of more weight leading to more strain on the cardiovascular system. However, a landmark discovery has dramatically refocused this understanding, suggesting that the true determinant of vascular health may not be the quantity of our fat but its quality. This reveals a complex biological conversation between our adipose tissue and our arteries that could revolutionize how we combat the world’s leading killer. This new line of inquiry repositions fat not as a passive burden but as an active, powerful regulator of our circulatory system, with one specific type holding the key to maintaining healthy blood pressure.

Beyond the Scale: What if the Real Key to Blood Pressure Lies Not in How Much Fat We Have, but What Kind?

The connection between carrying excess weight and developing high blood pressure is one of the most established in modern medicine, yet the precise biological reasons have remained surprisingly elusive. Hypertension contributes to the staggering burden of cardiovascular disease, the number one cause of death worldwide, making the search for its root causes a critical scientific endeavor. While public health messaging has understandably focused on weight management as a primary defense, this approach overlooks a more nuanced and potentially more powerful biological reality.

This emerging paradigm suggests a critical shift in focus from the amount of fat to the function of fat. Adipose tissue is not merely an inert storage depot for excess calories; it is a dynamic endocrine organ that secretes a host of signaling molecules that influence everything from metabolism to inflammation. Recent research powerfully argues that the functional identity of this tissue is a far more accurate predictor of cardiovascular risk than body mass index alone. It is within this functional context that a crucial distinction comes to light, setting the stage for a new understanding of vascular health.

The human body contains several types of fat, but two are central to this story. The most abundant is white adipose tissue, which is expertly designed to store energy for later use. In contrast, thermogenic fat—comprising both brown and beige varieties—acts as a metabolic furnace. Instead of storing calories, it burns them to generate heat, a process vital for maintaining body temperature. It is this heat-generating, energy-expending fat that scientists now believe plays an active and protective role in keeping our blood vessels flexible and our blood pressure in check.

The Long-Standing Mystery Connecting Fat to the World’s Leading Killer

To move from a compelling correlation to a proven cause, researchers embarked on a scientific journey known as “reverse translation.” The process began with an observation in human patients: individuals with more easily detectable brown fat consistently showed lower rates of hypertension and other cardiometabolic diseases. This intriguing clue from the clinic was taken back to the laboratory, where scientists could design controlled experiments to dissect the underlying biological mechanisms and uncover the precise molecular pathways responsible for this protective effect.

The cornerstone of the investigation was a meticulously designed experiment that isolated the role of beige fat with surgical precision. Instead of studying obese mice, which would introduce a host of confounding variables like systemic inflammation and insulin resistance, the team engineered mice that were lean and metabolically healthy in every respect but one. They selectively deleted a single gene, Prdm16, but only in the animals’ fat cells. This gene acts as a master switch, giving fat cells their protective, thermogenic beige identity. The result was a unique model: a healthy animal that simply could not form this specific type of protective fat, allowing for a direct and unambiguous test of its function.

The results were both immediate and alarming. In the absence of functional beige fat, the mice quickly developed hypertension. Their blood vessels, particularly the perivascular adipose tissue that wraps around arteries, lost their protective characteristics and began to overproduce angiotensinogen, the precursor to one of the body’s most potent blood-pressure-raising hormones. A physical examination of their arteries revealed a dangerous stiffening as fibrous tissue accumulated, reducing their natural elasticity. This provided the first definitive proof that the loss of beige fat’s function, entirely independent of obesity, is a direct cause of hypertension.

Unraveling the Mechanism: A Groundbreaking Scientific Detective Story

Armed with the knowledge that beige-fat-deficient tissue was instructing blood vessels to remodel themselves harmfully, the scientific team deployed an advanced genetic tool to zoom in on the molecular conversation. Using single-nucleus RNA sequencing, they were able to listen in on the genetic instructions being executed within individual vascular cells. This high-resolution analysis revealed that the cells lining the blood vessels had activated a distinct gene program that actively promoted fibrosis—the process of laying down stiff, scar-like tissue. The fat was not just passively present; it was actively sending out a signal that hijacked the blood vessels’ normal function.

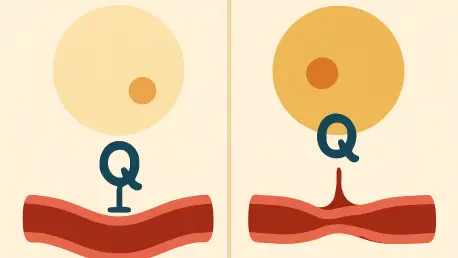

The next phase of this molecular detective story involved a large-scale search for the specific signaling molecule responsible. By analyzing massive datasets of gene and protein expression, the researchers identified a single culprit: an enzyme named Quiescin Sulfhydryl Oxidase 1, or QSOX1. Healthy beige fat, they discovered, acts as a natural suppressor, keeping the gene for QSOX1 switched off. However, when fat cells lose their beige identity due to the absence of the Prdm16 gene, they begin to churn out and secrete large quantities of QSOX1. This enzyme then acts directly on the surrounding vascular tissue, initiating the fibrotic cascade that leads to stiff arteries.

To provide the final, irrefutable piece of evidence, the team performed a brilliant genetic rescue experiment. They created a new line of mice in which both the beige fat gene (Prdm16) and the newly identified enzyme gene (Qsox1) were deleted. The outcome was definitive: despite their inability to form beige fat, these mice were completely protected from vascular stiffening and hypertension. Their blood pressure remained normal. This elegant experiment confirmed the entire signaling axis, proving that QSOX1 is the essential, indispensable link between dysfunctional fat and high blood pressure.

Pinpointing the Culprit: How a Single Enzyme Hijacks the System

The true power of this research is its direct relevance to human health, a connection solidified by analyzing large clinical databases. The investigation revealed that people who naturally carry mutations in their PRDM16 gene—the human equivalent of the one manipulated in the mice—have significantly higher blood pressure than the general population. This critical finding bridges the gap between the laboratory and the clinic, confirming that the QSOX1-driven mechanism uncovered in animal models is a key player in human hypertension, offering a compelling explanation for why some lean individuals still struggle with the condition.

The identification of QSOX1 as the key molecular driver of this process has profound implications for the future of cardiovascular medicine. For the first time, it provides a specific, druggable target that lies at the heart of the problem. Instead of relying on medications that manage the symptoms of high blood pressure—such as drugs that relax blood vessels or reduce blood volume—physicians may one day be able to prescribe therapies that block QSOX1 directly. Such a treatment would prevent vascular stiffening from occurring in the first place, representing a shift from management to prevention.

This discovery ultimately reshapes the strategic approach to cardiovascular health. It suggests that future interventions could move beyond the singular focus on weight loss and embrace strategies aimed at improving the health and function of our existing fat tissue. Therapeutic possibilities now include developing drugs that promote the formation of healthy beige fat, protect it from dysfunction, or directly inhibit the harmful pathway it controls. This research has illuminated a new frontier, offering hope for more precise and effective treatments for one of humanity’s most persistent and dangerous health challenges.

A New Frontier in Hypertension Treatment: Targeting the Source, Not Just the Symptoms

The discovery of the Prdm16-QSOX1 pathway has fundamentally altered the scientific understanding of fat’s role in cardiovascular health. It became clear that the conversation surrounding obesity and hypertension was far too simplistic. The research established that the functional identity of adipose tissue, particularly the protective capacity of thermogenic beige fat, was a critical and previously unappreciated regulator of blood pressure. The work provided a detailed molecular blueprint explaining how the loss of this single fat type could directly trigger vascular disease.

Pinpointing QSOX1 as the primary antagonist in this biological narrative opened an exciting new chapter in the development of antihypertensive therapies. It presented the pharmaceutical world with a novel and highly specific target. The prospect of creating a medication that could selectively block this enzyme offered a more proactive and targeted approach than ever before. This was not just another tool to manage symptoms; it was a potential way to dismantle the disease-causing mechanism at its source, protecting the arteries from the very damage that initiates hypertension.

Ultimately, this line of inquiry provided a powerful validation of the “reverse translation” model, successfully taking a clinical curiosity and transforming it into a concrete therapeutic target with life-saving potential. It underscored a paradigm shift away from viewing fat as a uniform entity and toward appreciating its complexity as a vital organ with distinct and powerful functions. The journey from a human observation to a molecular mechanism has not only solved a long-standing mystery but also laid the groundwork for a new generation of treatments aimed at preserving vascular health and preventing the onset of hypertension.Fixed version:

The relentless global rise of hypertension has long been shadowed by its close companion, obesity, creating a public health crisis that has puzzled scientists and clinicians for decades. For years, the prevailing wisdom held that the sheer volume of body fat was the primary driver of high blood pressure, a simple equation of more weight leading to more strain on the cardiovascular system. However, a landmark discovery has dramatically refocused this understanding, suggesting that the true determinant of vascular health may not be the quantity of our fat but its quality. This reveals a complex biological conversation between our adipose tissue and our arteries that could revolutionize how we combat the world’s leading killer. This new line of inquiry repositions fat not as a passive burden but as an active, powerful regulator of our circulatory system, with one specific type holding the key to maintaining healthy blood pressure.

Beyond the Scale: What if the Real Key to Blood Pressure Lies Not in How Much Fat We Have, but What Kind?

The connection between carrying excess weight and developing high blood pressure is one of the most established in modern medicine, yet the precise biological reasons have remained surprisingly elusive. Hypertension contributes to the staggering burden of cardiovascular disease, the number one cause of death worldwide, making the search for its root causes a critical scientific endeavor. While public health messaging has understandably focused on weight management as a primary defense, this approach overlooks a more nuanced and potentially more powerful biological reality.

This emerging paradigm suggests a critical shift in focus from the amount of fat to the function of fat. Adipose tissue is not merely an inert storage depot for excess calories; it is a dynamic endocrine organ that secretes a host of signaling molecules that influence everything from metabolism to inflammation. Recent research powerfully argues that the functional identity of this tissue is a far more accurate predictor of cardiovascular risk than body mass index alone. It is within this functional context that a crucial distinction comes to light, setting the stage for a new understanding of vascular health.

The human body contains several types of fat, but two are central to this story. The most abundant is white adipose tissue, which is expertly designed to store energy for later use. In contrast, thermogenic fat—comprising both brown and beige varieties—acts as a metabolic furnace. Instead of storing calories, it burns them to generate heat, a process vital for maintaining body temperature. It is this heat-generating, energy-expending fat that scientists now believe plays an active and protective role in keeping our blood vessels flexible and our blood pressure in check.

The Long-Standing Mystery Connecting Fat to the World’s Leading Killer

To move from a compelling correlation to a proven cause, researchers embarked on a scientific journey known as “reverse translation.” The process began with an observation in human patients: individuals with more easily detectable brown fat consistently showed lower rates of hypertension and other cardiometabolic diseases. This intriguing clue from the clinic was taken back to the laboratory, where scientists could design controlled experiments to dissect the underlying biological mechanisms and uncover the precise molecular pathways responsible for this protective effect.

The cornerstone of the investigation was a meticulously designed experiment that isolated the role of beige fat with surgical precision. Instead of studying obese mice, which would introduce a host of confounding variables like systemic inflammation and insulin resistance, the team engineered mice that were lean and metabolically healthy in every respect but one. They selectively deleted a single gene, Prdm16, but only in the animals’ fat cells. This gene acts as a master switch, giving fat cells their protective, thermogenic beige identity. The result was a unique model: a healthy animal that simply could not form this specific type of protective fat, allowing for a direct and unambiguous test of its function.

The results were both immediate and alarming. In the absence of functional beige fat, the mice quickly developed hypertension. Their blood vessels, particularly the perivascular adipose tissue that wraps around arteries, lost their protective characteristics and began to overproduce angiotensinogen, the precursor to one of the body’s most potent blood-pressure-raising hormones. A physical examination of their arteries revealed a dangerous stiffening as fibrous tissue accumulated, reducing their natural elasticity. This provided the first definitive proof that the loss of beige fat’s function, entirely independent of obesity, is a direct cause of hypertension.

Unraveling the Mechanism: A Groundbreaking Scientific Detective Story

Armed with the knowledge that beige-fat-deficient tissue was instructing blood vessels to remodel themselves harmfully, the scientific team deployed an advanced genetic tool to zoom in on the molecular conversation. Using single-nucleus RNA sequencing, they were able to listen in on the genetic instructions being executed within individual vascular cells. This high-resolution analysis revealed that the cells lining the blood vessels had activated a distinct gene program that actively promoted fibrosis—the process of laying down stiff, scar-like tissue. The fat was not just passively present; it was actively sending out a signal that hijacked the blood vessels’ normal function.

The next phase of this molecular detective story involved a large-scale search for the specific signaling molecule responsible. By analyzing massive datasets of gene and protein expression, the researchers identified a single culprit: an enzyme named Quiescin Sulfhydryl Oxidase 1, or QSOX1. Healthy beige fat, they discovered, acts as a natural suppressor, keeping the gene for QSOX1 switched off. However, when fat cells lose their beige identity due to the absence of the Prdm16 gene, they begin to churn out and secrete large quantities of QSOX1. This enzyme then acts directly on the surrounding vascular tissue, initiating the fibrotic cascade that leads to stiff arteries.

To provide the final, irrefutable piece of evidence, the team performed a brilliant genetic rescue experiment. They created a new line of mice in which both the beige fat gene (Prdm16) and the newly identified enzyme gene (Qsox1) were deleted. The outcome was definitive: despite their inability to form beige fat, these mice were completely protected from vascular stiffening and hypertension. Their blood pressure remained normal. This elegant experiment confirmed the entire signaling axis, proving that QSOX1 is the essential, indispensable link between dysfunctional fat and high blood pressure.

Pinpointing the Culprit: How a Single Enzyme Hijacks the System

The true power of this research is its direct relevance to human health, a connection solidified by analyzing large clinical databases. The investigation revealed that people who naturally carry mutations in their PRDM16 gene—the human equivalent of the one manipulated in the mice—have significantly higher blood pressure than the general population. This critical finding bridges the gap between the laboratory and the clinic, confirming that the QSOX1-driven mechanism uncovered in animal models is a key player in human hypertension, offering a compelling explanation for why some lean individuals still struggle with the condition.

The identification of QSOX1 as the key molecular driver of this process has profound implications for the future of cardiovascular medicine. For the first time, it provides a specific, druggable target that lies at the heart of the problem. Instead of relying on medications that manage the symptoms of high blood pressure—such as drugs that relax blood vessels or reduce blood volume—physicians may one day be able to prescribe therapies that block QSOX1 directly. Such a treatment would prevent vascular stiffening from occurring in the first place, representing a shift from management to prevention.

This discovery ultimately reshapes the strategic approach to cardiovascular health. It suggests that future interventions could move beyond the singular focus on weight loss and embrace strategies aimed at improving the health and function of our existing fat tissue. Therapeutic possibilities now include developing drugs that promote the formation of healthy beige fat, protect it from dysfunction, or directly inhibit the harmful pathway it controls. This research has illuminated a new frontier, offering hope for more precise and effective treatments for one of humanity’s most persistent and dangerous health challenges.

A New Frontier in Hypertension Treatment: Targeting the Source, Not Just the Symptoms

The discovery of the Prdm16-QSOX1 pathway has fundamentally altered the scientific understanding of fat’s role in cardiovascular health. It became clear that the conversation surrounding obesity and hypertension was far too simplistic. The research established that the functional identity of adipose tissue, particularly the protective capacity of thermogenic beige fat, was a critical and previously unappreciated regulator of blood pressure. The work provided a detailed molecular blueprint explaining how the loss of this single fat type could directly trigger vascular disease.

Pinpointing QSOX1 as the primary antagonist in this biological narrative opened an exciting new chapter in the development of antihypertensive therapies. It presented the pharmaceutical world with a novel and highly specific target. The prospect of creating a medication that could selectively block this enzyme offered a more proactive and targeted approach than ever before. This was not just another tool to manage symptoms; it was a potential way to dismantle the disease-causing mechanism at its source, protecting the arteries from the very damage that initiates hypertension.

Ultimately, this line of inquiry provided a powerful validation of the “reverse translation” model, successfully taking a clinical curiosity and transforming it into a concrete therapeutic target with life-saving potential. It underscored a paradigm shift away from viewing fat as a uniform entity and toward appreciating its complexity as a vital organ with distinct and powerful functions. The journey from a human observation to a molecular mechanism has not only solved a long-standing mystery but also laid the groundwork for a new generation of treatments aimed at preserving vascular health and preventing the onset of hypertension.