The recent MajesTEC-3 trial data has sent waves through the hematology community, suggesting a potential paradigm shift in how we approach relapsed multiple myeloma. The prospect of moving highly effective bispecific antibodies into earlier lines of treatment brings with it the tantalizing concept of a “functional cure,” but also raises critical questions about managing their potent side effects in broader clinical settings. We sat down with biopharma research and development expert Ivan Kairatov to unpack these remarkable findings, exploring the powerful synergy between Tecvayli and Darzalex, the practical implications for patient care, and how these therapies are reshaping the strategic landscape against CAR-T treatments.

The MajesTEC-3 trial data showed an 83% reduction in the risk of disease progression. Can you walk me through the specific patient outcomes that support the remarkable claim of “curative potential,” and what does a “functional cure” realistically look like in day-to-day life for these individuals?

The term “curative potential” is used carefully, but the data is undeniably compelling. It’s not just about that headline number of an 83% risk reduction. What truly gives us a glimpse of this potential is the durability of the response. When you look at the patients who achieved a response and maintained it for six months, an incredible 90% of them were still progression-free three years after the trial started. That’s a powerful indicator that we’re not just temporarily pushing the disease back; we are inducing a deep, lasting remission. For a patient, a “functional cure” means reclaiming a life that isn’t dictated by the disease. It means the myeloma is controlled so effectively and for so long that it becomes a background issue, not a daily crisis, potentially allowing them to live for years without further treatment and with a restored quality of life.

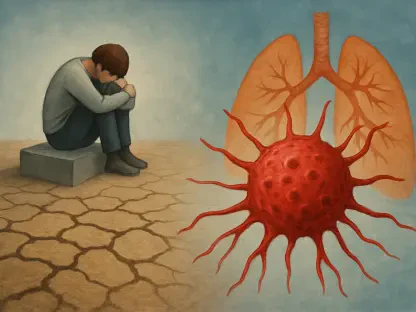

The presentation highlighted a serious risk of infection, with 13 deaths in the Tecvayli-Darzalex group. Could you detail the step-by-step mitigation protocols that were implemented and explain the practical challenges community oncologists will face when managing these risks outside of a specialized center?

This is the critical flip side of such a potent therapy. The high rate of infection, and tragically, the 13 deaths, underscores that this is not a simple treatment to administer. During the trial, investigators had to adapt the protocols to better protect patients. This involved proactive measures like providing immunoglobulin replacement therapy to bolster the patients’ own depleted immune systems, as well as administering antimicrobial medications to prevent infections before they could take hold. For a community oncologist, the challenge is immense. In a large academic center, you have teams dedicated to managing immunotherapy side effects. In a community practice, a doctor is juggling many different diseases. It requires an extremely high level of vigilance, constant monitoring, and the infrastructure to administer these supportive therapies, which may not be standard practice. Transitioning this regimen safely to the community will require a significant educational effort and a new standard of care for patient monitoring.

The combination achieved an 82% complete response rate, compared to 32% for the other regimens. Can you break down the biological synergy you believe exists between Tecvayli and Darzalex, and explain why adding this bispecific antibody creates such a dramatic improvement over existing Darzalex combinations?

Seeing a complete response rate jump from 32% to 82% is staggering and points to a powerful synergistic effect. Think of it as a two-stage attack on the myeloma cells. Darzalex is a monoclonal antibody that targets a protein called CD38, which is highly prevalent on the surface of myeloma cells. It essentially paints a target on them. Tecvayli is a bispecific antibody, meaning it has two arms: one grabs onto a myeloma cell, and the other grabs onto one of the patient’s own T-cells, which are the soldiers of the immune system. By adding Tecvayli, you’re not just passively targeting the cancer cells; you’re physically dragging a T-cell directly to the cell flagged by Darzalex and forcing an engagement. This creates a highly localized and potent immune attack right at the tumor site, resulting in a level of cancer cell elimination that is far beyond what Darzalex can achieve with standard partners like Velcade or Pomalyst.

An expert noted a preference for bispecifics over CAR-T for some patients in early relapse. Based on these findings, what specific patient profiles or clinical scenarios would make this Tecvayli combination the superior choice, and what are the key logistical advantages for treatment centers?

The logistical advantages are the driving force here. CAR-T therapy, while incredibly effective, is also incredibly complex. It requires harvesting a patient’s T-cells, shipping them to a centralized facility for genetic engineering, and then waiting weeks for the final product to be returned, all while the patient’s disease could be progressing. It can only be done at a limited number of highly specialized academic centers. This Tecvayli combination, however, is an “off-the-shelf” product. A patient who is relapsing for the first or second time and is being treated in a community setting—which accounts for up to half of all patients—is a perfect candidate. They can start treatment almost immediately without the travel, wait times, and manufacturing hurdles of CAR-T. For treatment centers, this means they can offer a cutting-edge immunotherapy to a much broader patient population without needing the massive infrastructure and specialized staff required for a CAR-T program.

Dr. Krishnan stated that bispecifics clearly work better when given earlier. Using data from this trial in patients with one to three prior treatments, what specific metrics or patient subgroup results best illustrate this point, and how does this change the strategic approach to the first relapse?

This trial is the perfect illustration of that principle. The key metric is the sheer depth and breadth of the response in this earlier-line population. Achieving an 82% complete response rate—meaning no detectable trace of disease—in patients who have only seen one to three prior therapies is a result you simply do not see when these drugs are used as a last resort in heavily pretreated individuals. Furthermore, the 83% reduction in progression risk demonstrates that using this powerful combination early on can fundamentally alter the disease course. Strategically, this completely reframes how we should think about the first relapse. The old model was often to use therapies sequentially, saving your most powerful agents for last. This data argues for the opposite: use your most effective combination right at that first relapse to try and knock the disease into a deep, durable remission, rather than waiting for it to become more complex and resistant.

What is your forecast for the future of multiple myeloma treatment based on these trends?

My forecast is that we are moving rapidly toward a future of “functional cures” being the explicit goal from the first relapse, not just a distant hope. We will see these highly effective bispecific and CAR-T immunotherapies become the standard of care in second- and third-line settings, and I suspect we’ll see trials moving them into the newly diagnosed setting for high-risk patients within the next few years. The major challenge and focus will shift from just discovering effective drugs to mastering their use. This means developing smarter, more robust supportive care protocols to manage toxicities in the community setting and using advanced diagnostics to identify which patients will benefit most from which combination, ultimately allowing us to deliver these transformative therapies safely and effectively to everyone who needs them.