As a Biopharma expert with a deep background in research, development, and the integration of technology in medicine, Ivan Kairatov offers a unique perspective on the intersection of patient experience and clinical outcomes. His insights bridge the gap between complex data and the real-world implications for patient care, particularly in oncology. This conversation explores a startling connection between color vision deficiency and bladder cancer survival, delving into the nuances of delayed diagnosis, the critical role of symptom recognition, and how the medical community can adapt to protect vulnerable patients. We will discuss why this visual impairment seems to affect bladder cancer outcomes so drastically while having little impact on colorectal cancer, examine potential strategies to overcome screening gaps in primary care, and look toward the future of personalized risk assessment in cancer detection.

A 52% higher mortality risk over 20 years was observed in bladder cancer patients with color vision deficiency. Can you walk me through the typical clinical journey that leads to this delayed diagnosis and describe the specific challenges these patients face in recognizing early warning signs?

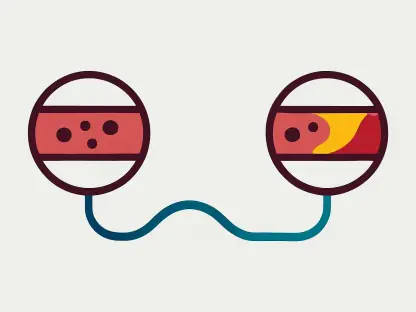

It’s a chilling statistic, and it paints a clear picture of a silent journey toward a late diagnosis. For up to 90% of bladder cancer patients, the very first—and often only—initial sign is painless hematuria, or blood in the urine. For a person with normal vision, seeing a pink or red tint in the toilet bowl is an immediate and alarming signal to call a doctor. But for someone with color vision deficiency, that red flag is invisible. They feel perfectly fine, there is no pain or discomfort, so they have no reason to believe anything is wrong. This lack of a visual cue allows the cancer to grow and progress unchecked, meaning that by the time other, more severe symptoms might appear, the disease is likely at a much more advanced and harder-to-treat stage. The delay isn’t a matter of days or weeks; it can be months or even longer, which is a critical window for effective treatment.

Why was a similar survival difference not seen in colorectal cancer patients? Please elaborate on how factors like routine screening and the presence of other symptoms, such as abdominal pain or weight loss, alter the diagnostic pathway for these individuals.

The diagnostic journey for colorectal cancer is fundamentally different, which is why we don’t see the same tragic disparity in survival rates. While blood in the stool is a key symptom, it’s rarely the only one. Patients might experience persistent abdominal pain, significant changes in bowel habits, or unexplained weight loss. These are powerful, non-visual signals that something is wrong, and they prompt a visit to the doctor regardless of whether the patient can see red. Furthermore, the healthcare system has a built-in safety net for this specific cancer. In the United States, routine screening for colorectal cancer is recommended for adults starting at age 45. This proactive approach means we are actively looking for the disease, often catching it before any symptoms—visual or otherwise—have a chance to manifest. Bladder cancer has no such routine screening recommendation for the general asymptomatic population, leaving the onus of detection entirely on the patient’s ability to spot that first, crucial sign.

Given that painless blood in the urine is the sole initial symptom for up to 90% of bladder cancer patients, what alternative detection methods or awareness campaigns could be implemented for high-risk individuals, especially since many with color vision deficiency remain undiagnosed?

This is where we need to get creative and shift our reliance away from patient-reported visual symptoms. A major hurdle is that most adults with color vision deficiency, especially milder forms, don’t even know they have it. So, awareness campaigns need to be designed with this in mind. Instead of just saying “look for blood,” messaging could be framed around “report any change in your urine’s appearance—whether it seems darker, cloudier, or just different.” For high-risk groups, such as older men who are more susceptible to both bladder cancer and color vision deficiency, we could promote more proactive, non-visual screening methods, perhaps through at-home urine tests that detect microscopic traces of blood that are invisible to the naked eye. The goal is to create a detection pathway that doesn’t depend on a sensory ability that a significant portion of the at-risk population may lack.

In the United States, screening for both color vision deficiency and asymptomatic bladder cancer is uncommon. Considering these gaps, what practical, step-by-step changes could primary care physicians implement to better identify at-risk patients before critical symptoms are missed?

Primary care physicians are on the front lines, and they can make a huge difference with a few simple, practical changes. First, incorporating a quick color vision screening into routine physicals for adults, particularly men, would be a game-changer. These tests are inexpensive, take only a minute, and would immediately identify individuals who cannot rely on visual cues for self-monitoring. Second, physicians can change the way they ask questions. Instead of a direct “Have you seen blood in your urine?”, they could ask more open-ended questions like, “Have you noticed any changes in your urine’s color or clarity?” This simple rephrasing avoids a yes/no answer based on color perception. For patients identified with color vision deficiency, a note could be made in their chart, flagging them for heightened awareness and potentially more frequent urinalysis, especially if they have other risk factors like a history of smoking.

The findings suggest an important association rather than a direct cause. What kind of future research is needed to confirm this link, and what specific data, like cancer staging at diagnosis, would be most crucial for developing new clinical guidelines?

This study is a fantastic starting point; it’s what we call “hypothesis-generating.” It flags a powerful association, but to establish a causal link and build clinical guidelines, we need more granular data. The most critical piece of information we’re missing is the cancer stage at the time of diagnosis. The hypothesis is that color-blind patients are diagnosed later, so we need to see if they are, in fact, presenting with more advanced, invasive tumors compared to their counterparts with normal vision. A large-scale prospective study would be ideal, where we screen a population for color vision deficiency and then follow them over time, recording the stage of any subsequent cancer diagnoses. This would give us the robust evidence needed to argue for changes in screening protocols and prove that a simple vision test could become a life-saving tool in cancer risk assessment.

What is your forecast for integrating visual health screenings into oncology risk assessment?

I believe we are on the cusp of a significant shift toward a more holistic view of patient health in oncology. For too long, we’ve thought of specialties in silos, but studies like this show that something as seemingly unrelated as ophthalmology can have profound implications for cancer survival. My forecast is that within the next decade, we will see simple sensory screenings, like color vision tests, become a standard part of primary care risk assessments, especially for high-risk demographics. The data is too compelling to ignore. It’s a low-cost, high-impact intervention that perfectly aligns with the push toward personalized and preventative medicine. Recognizing that a person’s ability to perceive the world visually directly impacts their ability to detect a deadly disease is a crucial step forward, and I expect it will pave the way for more integrated and intelligent screening strategies.