We are joined today by biopharma expert Ivan Kairatov to discuss a groundbreaking development in the fight against a virus that over 80% of the global population carries, often without a clue: human cytomegalovirus, or HCMV. While dormant for most, this stealthy pathogen poses a life-threatening risk to the immunocompromised—transplant recipients, cancer patients, and newborns—and stands as the most infectious cause of birth defects in the United States. A new collaboration has produced an engineered antibody that doesn’t just fight the virus, but outsmarts its clever defense mechanisms. Today, we’ll explore the fascinating molecular strategy behind what its creators call an “un-pickable lock,” delve into the laboratory evidence that shows how it restores our body’s natural defenses, and discuss how this paradigm shift in antiviral therapy could reshape our fight against a whole class of persistent viruses.

Professor Maynard described the engineered antibodies as “a lock that the virus can’t pick.” Could you walk us through the step-by-step process of identifying the specific regions on the IgG1 antibody to alter and how you re-engineered them to evade the virus’s hijacking proteins?

That description of a lock the virus can’t pick is incredibly apt because the process was a bit like being a molecular locksmith. The first step was understanding exactly how the virus was performing its heist. We knew that HCMV produces these tricky proteins called viral Fc receptors, or vFcγRs, which interfere with our natural defenses. Our initial work involved meticulously mapping precisely where on our own IgG1 antibodies—the real workhorses of our immune system—these viral proteins were latching on. Once we had pinpointed those specific binding sites, the delicate engineering began. This wasn’t a sledgehammer approach; it was molecular surgery, altering the antibody’s structure in just those key regions. The result is a sophisticated antibody that is essentially invisible to the virus’s hijacking proteins. The vFcγRs try to grab on, but their grip just slips off, while crucially, the part of the antibody that calls in the immune system’s cavalry—the Natural Killer cells—remains perfectly intact and fully functional.

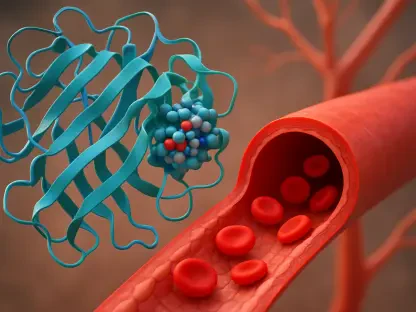

The research highlights a “tug-of-war” between the virus and the immune system. In your lab experiments, what specific metrics or observations demonstrated that your engineered antibody was successfully restoring Natural Killer cell activation and significantly reducing the spread of the virus between cells?

That “tug-of-war” is the perfect way to visualize what’s happening at the cellular level. In a standard infection model in the lab, you can almost see the virus winning that fight. The normal antibodies are present, but they are completely neutralized, hijacked by the virus’s vFcγRs, and the immune response is just eerily silent. The infected cells become viral factories, and the infection quietly spreads from one cell to its neighbors without any resistance. But when we introduced our engineered antibody into these infected cell cultures, the dynamic shifted dramatically. The most compelling observation was seeing the restored activation of the Natural Killer, or NK, cells. We could physically observe them engaging with the infected cells and clearing them out, a critical process that was completely blocked before. Quantitatively, our key metric was viral dissemination. We measured how effectively the virus could spread between cells, and with our antibody in the mix, we saw a significant reduction in this spread, effectively containing the infection in a way we just don’t see otherwise.

This work is called a “paradigm shift” away from just neutralizing a virus. How might this immune-empowering approach be adapted for other herpesviruses that use similar evasion tactics, and what key challenges do you anticipate in applying this technique to different pathogens?

For decades, the dominant strategy in antiviral therapy has been direct neutralization—creating a drug or antibody that physically blocks the virus from entering a cell. It’s a direct assault on the pathogen itself. This work represents a fundamental shift in that thinking. We are not just attacking the virus; we are disarming its defenses against our own immune system. We’re essentially cutting its propaganda network and letting our body’s own expert assassins, the NK cells, do the job they were designed for. It’s about empowering the host, not just inhibiting the pathogen. This is incredibly exciting because HCMV isn’t alone; many other herpesviruses use similar immune evasion tactics. The blueprint we’ve created could absolutely be adapted. The main challenge will be the specificity. Each virus has evolved its own unique molecular key to pick our immune locks, so for every new target, it will require detailed investigation to identify the right sites to re-engineer. It’s not a one-size-fits-all solution, but it is a highly adaptable platform for creating bespoke therapies.

Given that current HCMV antivirals can have toxic side effects, what are the next crucial testing milestones for this antibody? Please elaborate on how you envision combining it with other therapies to create a safer, more comprehensive treatment strategy for vulnerable patients.

The toxicity of current treatments is a major driver for this work. For an organ transplant recipient or a cancer patient whose system is already under immense stress, adding a therapy with harsh side effects is a huge clinical challenge, so the need for safer alternatives is urgent. Before this antibody can reach patients, it must go through several more critical rounds of pre-clinical testing to ensure its safety and efficacy in biological systems far more complex than a lab dish. We need to confirm that it works as intended in a living organism without causing any unforeseen problems. Looking ahead, I don’t see this as a silver bullet that replaces everything else, but rather as a powerful new tool in the arsenal. The most exciting prospect is a combination strategy. Imagine pairing our immune-empowering antibody with a low dose of a traditional antiviral drug. The antibody would prevent the virus from hiding and spreading, exposing it to the antiviral drug that could then clear it more effectively. This could create a synergistic effect, allowing us to use far less of the toxic drugs and dramatically improving patient safety.

What is your forecast for the development of new antibody-based therapies against common, persistent viruses like HCMV over the next decade?

My forecast is one of profound optimism. For too long, we’ve treated persistent viruses like HCMV—which, again, over 80% of us carry for life—as something to be managed only when they cause acute disease. I believe the next decade will see a major shift towards therapies that actively re-balance the host-pathogen relationship in our favor, moving beyond simple suppression and into the realm of true immune empowerment. We will see more of these “smart” antibodies, engineered not just to bind to a target, but to perform complex functions like evading viral defenses and actively recruiting specific immune cells. For a virus that is the leading infectious cause of birth defects, affecting up to 2% of pregnancies worldwide, this isn’t just an academic exercise; it’s a technology with the potential to prevent lifelong disability and save lives. Ultimately, these approaches will lead to a future where we can give our immune systems a permanent advantage, turning these lifelong, stealthy infections into truly manageable conditions with minimal long-term impact on health, especially for the most vulnerable among us.