I’m thrilled to be speaking with Ivan Kairatov, a renowned biopharma expert whose extensive experience in research and development has positioned him at the forefront of cutting-edge cancer treatment technologies. Today, we’ll dive into the groundbreaking work on nanodots made from molybdenum oxide, exploring how these tiny particles are designed to target cancer cells while sparing healthy ones. Our conversation will touch on the innovative chemistry behind these particles, their unique ability to function without light, the potential for cost-effective scalability, and the exciting next steps in refining their precision for clinical applications. Join us as we uncover the science, challenges, and personal insights driving this promising advancement in cancer therapy.

Can you walk us through the development process of these molybdenum oxide nanodots and how your team fine-tuned their chemical composition to target cancer cells?

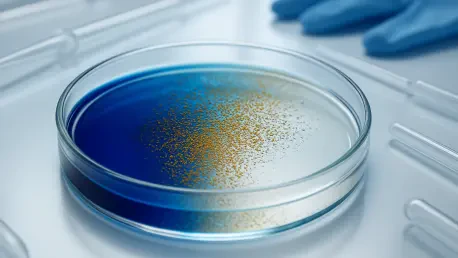

Thank you for having me. Developing these nanodots was a journey of meticulous experimentation and collaboration. We started with molybdenum oxide, a compound often used in electronics, and explored how we could tweak its chemical makeup by introducing small amounts of hydrogen and ammonium. This adjustment was critical—it altered how the particles managed electrons, boosting their production of reactive oxygen molecules, which are essentially unstable oxygen forms that can damage cell components. I remember a particularly tough moment when early tests showed insufficient selectivity; we spent countless late nights in the lab, adjusting ratios and running simulations until we hit a balance that worked. The breakthrough came when we saw these particles kill three times more cervical cancer cells than healthy ones in just 24 hours. That result was a rush—seeing the data come alive on the screen felt like we’d cracked open a new door in cancer treatment.

What’s happening at the cellular level that allows these nanodots to be so selective in stressing cancer cells over healthy ones?

That’s a fascinating aspect of this work. Cancer cells naturally exist under higher stress levels compared to healthy cells due to their rapid growth and metabolic demands. Our nanodots push this stress just a bit further by generating oxidative stress through reactive oxygen molecules, which trigger apoptosis—essentially the cell’s self-destruct mechanism. Healthy cells, with lower baseline stress, can handle this additional push without collapsing. I recall a pivotal day in the lab when we first observed this under the microscope; the cancer cells were visibly breaking down while nearby healthy cells remained intact—it was like watching a targeted demolition. This selectivity isn’t perfect yet, but it’s a promising step toward minimizing the collateral damage seen in many traditional therapies. We’re still refining the mechanism, but seeing those early results gave us a profound sense of hope for gentler, more precise treatments.

I’m intrigued by the fact that these particles don’t require light to activate, which sets them apart from other technologies. Can you explain how you achieved this dark-activated reaction and what it means to you personally?

Absolutely, that’s one of the features we’re most excited about. Most similar technologies rely on light to trigger reactions, which limits their use to surface-level tumors or requires invasive light delivery methods. With our molybdenum oxide nanodots, we discovered during testing that they could produce reactive oxygen species in complete darkness by fine-tuning their electron-handling properties through chemical doping. It started with a hunch—we ran experiments in controlled dark conditions, and step by step, adjusted the composition until we saw consistent activity without any light stimulus. I’ll never forget the moment we confirmed this; it was late, the lab was dim, and the team erupted in cheers over a simple graph showing sustained reaction rates. Personally, this excites me because it opens up possibilities for treating deeper tumors non-invasively. It’s a reminder of how thinking outside conventional constraints can yield solutions that feel almost like science fiction coming to life.

Using molybdenum oxide instead of more expensive metals like gold or silver seems like a strategic choice. Can you share why your team went this route and how it might shape the future of scaling this technology?

We chose molybdenum oxide deliberately for its practicality. Unlike noble metals like gold or silver, which can be costly and sometimes pose toxicity risks, molybdenum oxide is a common, affordable material often used in industrial applications. This makes it a safer bet for both development and eventual manufacturing at scale. During our research, we compared costs and found that using molybdenum oxide could reduce production expenses significantly compared to alternatives, though I don’t have exact figures at hand—it was a striking difference. Beyond cost, its relative abundance means we’re not bottlenecked by scarce resources, which is crucial for widespread adoption. I think back to discussions with my team about making treatments accessible; choosing this material felt like a small but meaningful step toward that goal. If we can move this to industry partnerships, I believe it could democratize access to advanced therapies in a way that rarer materials simply can’t.

Looking ahead, your team is focusing on targeted delivery systems to ensure these nanodots activate only inside tumors. Can you elaborate on the challenges and initial strategies you’re exploring to achieve this precision?

That’s our next big hurdle, and it’s a complex one. The goal is to prevent the nanodots from releasing reactive oxygen species in healthy tissues, which means we need a delivery mechanism that activates them only when they reach the tumor environment. We’re exploring ideas like coating the nanodots with biocompatible materials that respond to specific tumor markers—think of it as a lock-and-key system where the tumor’s unique chemistry is the key. Initial experiments involve testing these coatings in cell cultures to see if they can remain inert until they encounter cancer-specific conditions, like a particular pH or enzyme. One memorable challenge was when an early coating broke down too soon; we had to go back to the drawing board, literally sketching out molecular structures over coffee-stained notebooks. We’re aiming for near-zero off-target effects, and while it’s early days, every small success feels like building a safer future for patients. It’s painstaking work, but the potential to spare healthy tissue keeps us driven.

One striking result was the nanodots breaking down a blue dye by 90 percent in just 20 minutes, even in darkness. Can you explain the significance of this test and what it felt like to witness that outcome?

That test was a powerful proof of concept for us. Breaking down the blue dye by 90 percent in 20 minutes demonstrated the sheer potency of the nanodots’ oxidative reactions, even without light—a clear indicator of their potential to disrupt cancer cell components in a similar way. We set up the experiment by dissolving the dye in a solution with our nanodots, sealed it in a dark chamber, and monitored the color change over time using a spectrophotometer. Each minute felt like an eternity as we watched the readings drop, and when we hit that 90 percent mark, there was this collective gasp in the lab—it was tangible evidence of our particles’ strength. Personally, it hit me hard; I thought about patients who might one day benefit from a treatment this relentless against cancer. It’s not just a number on a chart; it’s a glimpse of hope, a reminder of why we push through the long hours and setbacks. That moment still gives me chills when I think about it.

What is your forecast for the future of nanotechnology in cancer treatment, especially with innovations like these nanodots on the horizon?

I’m incredibly optimistic about where nanotechnology is headed in cancer care. With innovations like our molybdenum oxide nanodots, I foresee a shift toward therapies that are not only more precise but also more accessible due to lower costs and scalable materials. In the next decade, I expect we’ll see targeted delivery systems become sophisticated enough to virtually eliminate side effects, transforming cancer treatment into something as tailored as a custom-made suit. Challenges remain—translating lab results to animal and human trials is a steep climb—but the momentum in this field is undeniable. I envision a future where patients face less fear of collateral damage from treatments, and that’s what keeps me motivated. We’re just scratching the surface, but every step feels like we’re inching closer to a tipping point where nanotechnology could redefine how we fight this disease.