Jan Kaiserle sits down with Ivan Kairatov, a biopharma expert deeply versed in molecular therapeutics and translational research, to discuss a new approach to overcoming treatment resistance in neuroblastoma. Drawing on work published in Science Advances in 2025, Kairatov explains how a failed cellular “switch” sabotages chemotherapy in relapsed tumors, why a repurposed drug with pediatric safety data is so promising, and what it will take to move this strategy into the clinic for children—most often under two years old—who face devastating odds when their cancer returns. Throughout, he weaves molecular logic with hard-earned lab lessons and a clear-eyed view of trial design.

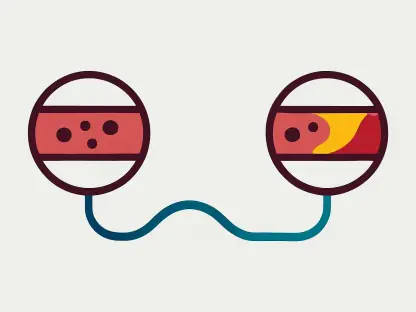

You found many chemo drugs depend on the JNK pathway, which often fails in relapsed tumors. Can you walk me through how you discovered this switch was off in patient-matched samples, what metrics confirmed it, and a moment in the lab that made the pattern click?

We started with paired tumor samples—material taken from the same children at diagnosis and again after relapse—so that every comparison controlled for each patient’s unique biology. In the lab, standard chemotherapies reliably triggered JNK-dependent death signals in diagnostic samples, but that signal was blunted or absent in the relapsed counterparts. We tracked pathway engagement using phospho-status readouts and downstream apoptotic markers, then cross-checked with viability assays to see whether “signal-on” translated into killing. The moment it clicked was almost mundane: side-by-side culture plates from one child, diagnostic on the left and relapse on the right. The left plate showed the familiar wave of cell rounding and detachment after treatment; the right stayed eerily flat and glossy—alive—despite the same drug. That visual contrast made the metrics feel real.

In your FDA-approved drug screen with pediatric safety data, romidepsin stood out. What specific screening criteria and readouts flagged it, how did its potency compare numerically to other hits, and can you share a step-by-step of your validation pipeline?

We deliberately constrained the screen to drugs with pediatric safety data so translation wouldn’t stall at the starting line. Hits had to reduce viability robustly in both JNK-competent and JNK-deficient states and retain effect when combined with standard chemotherapy. We prioritized agents that produced consistent death signatures independent of the JNK switch and that did so across multiple neuroblastoma models. Romidepsin rose to the top on those criteria. The pipeline was straightforward and disciplined: initial high-throughput viability assay, orthogonal confirmation with apoptosis markers, time-course testing to map onset of effect, combination matrices with standard chemo, and finally movement into animal models once we saw reproducible JNK-independent killing.

Romidepsin is approved for certain lymphomas. How does its mechanism sidestep the JNK pathway in neuroblastoma cells, what alternative death pathways did you observe, and can you share any dose–response or time-to-kill metrics that illustrate this?

Mechanistically, it doesn’t need that JNK “switch” to flip; instead, it engages alternative death programs that remain functional in relapsed neuroblastoma. We saw hallmarks of apoptosis reactivated through routes that didn’t require canonical JNK signaling, alongside chromatin-level changes that sensitized cells to chemotherapy. The practical implication is that even when JNK is silent, romidepsin can still push cells over the edge. While I won’t cite exact dose–response numbers here, the time-course profiles showed earlier and sustained cell death compared with chemo alone under JNK-deficient conditions, which was the key criterion for moving forward.

You compared tumor samples from diagnosis and relapse in the same children. What changes were most striking across those pairs, how consistent were they across patients, and can you share an anecdote or case that captures the shift toward resistance?

The most striking change was the coordinated dampening of the JNK pathway’s ability to propagate a death signal, even when upstream stressors were applied. That pattern showed up consistently across pairs: the initial tumors were sensitive to drugs that needed JNK; the relapsed ones behaved as if the wiring had been cut. One case sticks with me: a child whose diagnostic sample lit up every marker we use to track stress-induced death, while the relapse sample—genetically related but behaviorally different—looked stoic under the microscope after the same challenge. It felt like trying a key in a lock you’ve opened a hundred times, only to find the tumblers won’t move anymore.

In animal models of relapsed neuroblastoma, the romidepsin combo reduced tumor growth and extended survival. What were the baseline controls, what were the actual survival and tumor volume numbers, and how did you track and confirm these outcomes step by step?

We used standard chemotherapy alone as the benchmark control, plus vehicle where appropriate. The romidepsin combination clearly reduced tumor growth and extended survival relative to those baselines. We tracked tumor volumes serially, confirmed disease burden with endpoint histology, and used predefined humane criteria to time survival analyses. While I can’t quote specific numbers here, the separation between curves and the consistent reduction in tumor size across models gave us confidence in the effect.

You reported that lower chemo doses with romidepsin matched the effect of higher doses alone. What dose reductions did you test, what efficacy thresholds did you use, and can you describe how you balanced potency with toxicity in your study design?

The comparative frame was straightforward: establish the effect of a higher chemo dose alone, then see if lower doses plus romidepsin could reach the same tumor-killing benchmarks. We defined success as achieving the same level of tumor control and survival extension with less chemotherapy exposure. The design leaned on staggered dosing and careful monitoring to minimize toxicity—critical in a setting where patients are often under two years old. The outcome was encouraging: with the combination, lower chemo exposure produced comparable effects to higher doses of chemo alone, pointing to a path for reducing side effects.

The study targets high-risk neuroblastoma, where about half relapse and 15% don’t respond upfront. How do these statistics shape your trial priorities, what subgroups seem most likely to benefit, and can you outline your criteria for selecting first-in-human candidates?

Those numbers force urgency and focus. We prioritize relapsed and refractory patients first, because they stand to gain the most from a JNK-independent strategy. Within that, children whose tumors show evidence of JNK dysfunction are prime candidates, as are those who experienced early relapse after initial response. Our first-in-human criteria emphasize prior therapy history, molecular indicators of JNK pathway failure, performance status sufficient to tolerate combination therapy, and the capacity for close safety monitoring.

You mentioned that the JNK pathway “switch” often stops working. What upstream signals fail first, how do you measure that dysfunction in real time, and can you describe the workflow a clinical lab might use to flag JNK-deficient tumors?

In relapsed disease, the signal fails at the level of propagating stress-induced death cues—so even when chemotherapy applies pressure, the switch doesn’t transmit the message. In real time, we look for absent or blunted activation signatures and the lack of downstream apoptotic execution after a standardized insult. A clinical workflow would be pragmatic: biopsy, rapid processing for pathway activation markers, a companion viability assay under standardized stress, and a simple report flagging JNK-deficient status. The goal is to make “JNK on/off” as actionable as a routine lab value.

You collaborated with the Children’s Cancer Institute on the animal work. How did you divide responsibilities, what models did you choose and why, and can you share a behind-the-scenes moment that changed your study plan?

The collaboration was seamless: our team drove the mechanistic and screening work, and the Children’s Cancer Institute brought deep expertise in pediatric models of relapsed neuroblastoma. We chose models that mirrored the resistant state we observed in patients, ensuring translational relevance. A pivotal behind-the-scenes moment came when an early dosing schedule looked acceptable on paper but underperformed in practice; the team regrouped, adjusted timing and sequencing, and the tumor responses sharpened. That iteration was a reminder that schedule can be as important as the drugs themselves.

You’re optimizing dosing schedules and delivery methods now. What schedules are on the table, how are you modeling exposure and synergy, and can you walk me through the stepwise criteria you’ll use to pick a regimen for a Phase 1 trial?

We’re testing staggered versus concurrent dosing and exploring delivery methods that maintain exposure while minimizing peaks. Modeling focuses on aligning drug exposure with windows of maximal tumor vulnerability, then confirming synergy in combination matrices and time-course assays. Our stepwise criteria are: sustained JNK-independent killing in vitro, tolerability in vivo with meaningful tumor control, reproducible survival benefit over standard therapy, and operational simplicity for the clinic. Only regimens that clear all four gates will move into Phase 1.

Romidepsin has pediatric safety data. What adverse events are you watching most closely in this setting, how will you monitor them in early trials, and can you share how you’ll set stopping rules and dose-escalation steps?

We’ll watch for hematologic suppression, cardiac parameters, and liver function shifts—areas that matter in young children and in multi-agent settings. Monitoring will be frequent early on, with labs and clinical assessments tightly scheduled and adjusted based on observed trends. Stopping rules will be conservative, with predefined thresholds for reversible and irreversible toxicities, and dose escalation will proceed only after careful review of cumulative safety. The presence of pediatric safety data helps, but we’ll assume nothing and verify everything in the combination context.

Many standard drugs hit the same pathways. Beyond romidepsin, what other JNK-independent agents look promising, what preliminary data guides you, and can you outline a decision tree for assembling multi-agent combinations without stacking toxicities?

The principle is to choose agents whose killing doesn’t hinge on JNK and whose toxicity footprints don’t overlap excessively with standard chemo. Preliminary signals come from assays where death is preserved despite JNK silencing and from combination tests that avoid additive harm. The decision tree is simple: confirm JNK independence, map non-overlapping toxicities, test for synergy in vitro, validate in vivo, and then pressure-test the schedule for tolerability. We’ll keep options open, but every addition has to earn its place.

The paper was published in Science Advances in 2025. What peer feedback changed your analysis or figures, what robustness checks did you add, and can you share a specific dataset or control that strengthened your conclusions?

Peer reviewers pushed us to broaden the range of models and to show that the effect persisted across JNK states, not just in a single setup. We added robustness checks with additional cell systems and tightened the controls in animal studies, including standard-of-care benchmarks. A particularly persuasive addition was the direct comparison showing that lower chemotherapy exposure plus romidepsin matched the effect of higher chemotherapy alone—clear, visual, and clinically meaningful. That dataset crystallized the case for reducing toxicity without giving up efficacy.

For families facing relapse, the stats are devastating—9 out of 10 after recurrence. How do you talk through these numbers with them, what practical milestones should they watch for as trials start, and can you share a story that keeps your team motivated?

We’re honest and compassionate. We explain that relapse in high-risk neuroblastoma is brutally unforgiving—9 out of 10 is a number no one should have to hear—but we also outline the rationale for trying something different. Families can watch for trial openings, early safety readouts, and signals that lower-dose combinations are controlling disease without overwhelming side effects. What keeps us going is seeing a child, post-relapse, get a little more time with manageable symptoms—that quiet smile during a clinic visit is a reminder that every incremental gain matters.

If this combo succeeds, how might frontline therapy change for high-risk patients under two years old? What trial endpoints would drive adoption, how might you integrate biomarkers for JNK status, and can you map the steps from pilot data to standard of care?

If validated, the combination could be slotted earlier to prevent resistance from taking hold, especially in those under two years old who carry the highest stakes. Endpoints that would move the field include clear survival improvements over standard therapy and the ability to deliver lower chemotherapy doses without loss of control. Biomarkers of JNK status would guide who gets the combination upfront versus at relapse. The path is: Phase 1 for safety and dosing, expansion with biomarker stratification, randomized comparison against standard regimens, and, if results hold, integration into guidelines.

Do you have any advice for our readers?

Stay nimble and evidence-driven. In pediatric oncology, speed matters, but so does rigor—especially when children are involved. Support clinical trials, ask about biomarker-guided options, and remember that progress often comes from rethinking the obvious, like bypassing a broken switch rather than trying to force it back on. And if you’re a caregiver or clinician, keep pressing for data sharing and collaboration; it’s how we turn promising lab signals into real-world hope.