I’m thrilled to sit down with Ivan Kairatov, a renowned biopharma expert with extensive experience in research and development, particularly in the realm of technology and innovation in the industry. Today, we’re diving into the groundbreaking ASAP study, a pivotal trial in blood cancer research, and exploring its implications for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) treatment. We’ll discuss how this study challenges conventional approaches, the role of personalized medicine in transplantation, and the critical contributions of organizations like DKMS in advancing scientific progress. Join us as we uncover insights that could reshape the future of AML care.

Can you start by explaining what the ASAP study is and why it holds such significance for blood cancer treatment?

The ASAP study, which stands for “As Soon As Possible,” is a landmark randomized controlled trial focused on acute myeloid leukemia, or AML. Its primary goal was to evaluate whether immediate allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation after intensified conditioning could be as effective as the current standard of care, which involves remission induction through salvage chemotherapy before transplant. This study is significant because it directly challenges long-held assumptions about the necessity of aggressive pre-transplant chemotherapy, potentially offering a pathway to reduce patient burden while maintaining similar outcomes. It’s a bold step toward rethinking how we approach AML treatment.

How did the two treatment approaches in the ASAP study differ in their strategies for managing AML patients?

The ASAP study compared two distinct approaches. The standard of care arm involved remission induction with intensive salvage chemotherapy to reduce leukemia burden before transplantation. This has been the conventional route for many years, aiming to get patients into remission first. In contrast, the alternative treatment arm prioritized immediate transplantation after intensified conditioning, paired with less aggressive disease control methods like milder chemotherapy or simply monitoring leukemia progression. This approach sought to minimize delays and reduce exposure to harsh treatments before the transplant itself.

What did the long-term results of the ASAP study reveal about patient outcomes across these two approaches?

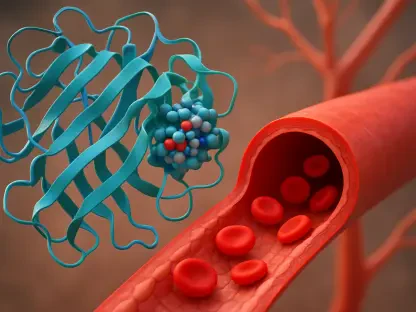

The long-term follow-up, with a median of 61 months, showed striking similarities in overall survival between the two groups. The standard of care arm had a five-year survival rate of 47.5%, while the alternative treatment arm, with immediate transplantation, was very close at 46.1%. Notably, patients in the alternative arm spent about a month less in the hospital and faced fewer adverse events compared to those undergoing intensive chemotherapy in the standard arm. While the study couldn’t formally prove non-inferiority, it suggests that immediate transplantation could be a viable option for many patients, especially to reduce treatment-related hardships.

Why are factors like age and AML genetics considered such critical determinants of survival in this context?

Age and AML genetics are pivotal because they reflect the intrinsic challenges of the disease and the patient’s capacity to withstand treatment. Older patients often have comorbidities or reduced resilience to intensive therapies, which can impact outcomes. AML genetics, classified by frameworks like the ELN 2022 criteria, determine the disease’s aggressiveness and response to treatment. For instance, the ASAP study found five-year survival rates of 66% for favorable risk AML, 53% for intermediate risk, and just 34% for adverse risk. These factors often outweigh treatment strategy in predicting long-term success, highlighting the need to tailor approaches based on individual profiles.

The study found that reducing leukemia burden before transplant didn’t always lead to better survival. Can you unpack why this was such a surprising finding?

This was a counterintuitive result because the prevailing belief in AML treatment has been that minimizing leukemia burden through aggressive chemotherapy before transplant would improve outcomes by reducing the risk of relapse. However, the ASAP study showed that when using intensive conditioning regimens just before transplantation, the pre-transplant leukemia burden didn’t have the expected impact on survival. It suggests that the conditioning itself might be sufficient to control the disease in many cases, challenging us to rethink the necessity of prolonged, toxic pre-transplant therapies and focus more on optimizing other aspects of care.

How do the ASAP findings pave the way for more personalized approaches in transplantation for AML patients?

The ASAP study underscores that one-size-fits-all strategies don’t fully address the complexities of AML. Survival is heavily influenced by intrinsic disease biology, like genetics, rather than just pre-transplant strategies. This points to a future where treatments are tailored based on specific risk profiles—whether favorable, intermediate, or adverse. Additionally, the study highlights the urgent need for research into novel bridging therapies that are less toxic and post-transplant maintenance approaches to prevent relapse, especially for high-risk groups. It’s a call to action for precision medicine in transplantation, ensuring we match the right strategy to the right patient.

Can you share more about DKMS’s role in the ASAP study and how it aligns with their broader mission to combat blood cancer?

DKMS played a central role in initiating and executing the ASAP study, reflecting their commitment to driving innovation in blood cancer treatment. As an international non-profit, their mission is to improve survival and healing chances for patients by investing in research that challenges existing standards and explores new frontiers. Beyond ASAP, DKMS partners with medical experts globally, funds clinical trials, and supports young scientists through initiatives like research grants and awards. Their focus on scientific questions free from commercial bias ensures that advancements prioritize patient access and holistic care worldwide.

What is your forecast for the future of AML treatment in light of studies like ASAP?

I’m optimistic that AML treatment will increasingly move toward personalized, biology-driven strategies over the next decade. Studies like ASAP are laying the groundwork by showing us that we can sometimes achieve comparable outcomes with less aggressive approaches, reducing patient suffering. I foresee a future where genetic profiling becomes standard at diagnosis, guiding tailored therapies from the start. Additionally, advancements in novel drugs for bridging to transplant and maintenance therapies post-transplant will likely improve outcomes, especially for adverse-risk patients. The focus will be on balancing efficacy with quality of life, and I believe collaborative efforts, like those led by organizations such as DKMS, will be key to making this a reality.