The silent pandemic of antibiotic resistance, a threat the World Health Organization has elevated to one of the greatest dangers to modern medicine, has an unexpected and pervasive accomplice in the fields and farms that feed the world. A primary pathway for this threat originates in livestock manure, which, laden with antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) from veterinary treatments, contaminates soil, water, and ultimately the human food chain. While conventional composting has been a standard approach to managing this agricultural waste, a far more effective, low-energy, and nature-based solution is emerging from the ground up. Vermicomposting, a process that harnesses the digestive power of earthworms, presents a robust technological answer, transforming these humble invertebrates into living bioreactors that not only neutralize a significant public health risk but also generate a high-value organic fertilizer that bolsters sustainable agriculture. This method consistently outperforms traditional techniques, offering a more stable and powerful tool in the global fight against antimicrobial resistance.

The Shortcomings of Conventional Methods

Current strategies for mitigating antibiotic resistance from agricultural waste are fraught with inconsistency, a critical flaw given the scale of the problem. Conventional composting, long considered a viable method for treating livestock manure, often yields unstable and unpredictable results. Under certain conditions, this process can fail to adequately reduce the abundance of ARGs and, in some instances, may even inadvertently create an environment where key resistance markers rebound to their initial levels or higher. This unreliability is a major concern, as it means that manure treated through these methods can still act as a significant reservoir for resistance. The dissemination of these genes, along with the mobile genetic elements (MGEs) that facilitate their transfer between bacteria, poses a direct and ongoing threat. When this inadequately treated manure is applied to agricultural land, it effectively seeds the environment with the genetic blueprints for antibiotic resistance, undermining efforts to control its spread.

The pathway of contamination from farm to human is direct and well-documented, making the failure of conventional methods particularly alarming. Once manure containing ARGs is spread on fields, these genes can integrate into the native soil microbiome. From there, they are easily transported into waterways through agricultural runoff or taken up by crops grown in the contaminated soil. This creates multiple avenues for entry into the human food chain and, subsequently, the human gut. The presence of these resistance genes in our own microbial ecosystems can render critical antibiotic treatments ineffective when they are needed most. The inability of standard composting to consistently sever this link in the chain of transmission highlights a pressing need for superior, more dependable solutions. Vermicomposting has emerged as that alternative, demonstrating a remarkable capacity to disrupt this dangerous cycle with far greater efficiency and consistency, thereby making the recycling of agricultural nutrients a much safer practice for both public health and the environment.

Nature’s Bioreactor in Action

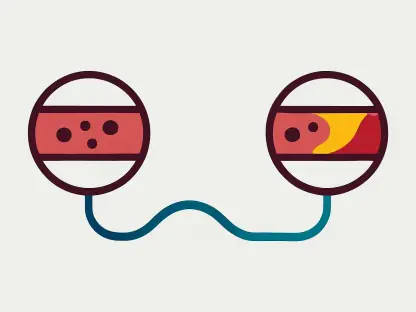

Earthworms function as remarkably sophisticated living bioreactors, deploying an integrated suite of physical, chemical, and biological mechanisms to decontaminate manure. Their constant burrowing and feeding activities are not random; they systematically re-engineer the waste material, dramatically increasing its porosity and aeration. This physical transformation creates an oxygen-rich, or aerobic, environment that is fundamentally inhospitable to many of the anaerobic bacteria that are common carriers of resistance genes. By altering the very conditions of the microbial habitat, earthworms initiate a significant ecological shift. Furthermore, this enhanced aeration accelerates the natural decomposition of residual antibiotic compounds present in the manure. By breaking down these selective agents, the process removes the environmental pressure that would otherwise favor the survival and proliferation of resistant bacterial strains, tackling the problem at one of its primary roots and setting the stage for deeper decontamination within the worm itself.

The true power of this natural technology is revealed inside the earthworm’s digestive tract, a potent processing center where multiple decontamination processes converge. As manure passes through the gut, it is subjected to intense mechanical grinding, which physically damages bacterial cells. This is complemented by a cocktail of powerful digestive enzymes and the actions of a specialized gut microbiome, which work in concert to disrupt both intracellular and extracellular DNA, including the ARGs. This intense biological processing does more than just eliminate individual resistant microbes; it fundamentally restructures the entire microbial community of the manure. The process facilitates a shift away from fast-growing, opportunistic bacteria that frequently host ARGs and MGEs, promoting instead the growth of more stable and functionally beneficial microbial groups essential for decomposition and nitrogen fixation. This ecological restructuring is a key advantage, as it builds a resilient microbial community that is inherently less conducive to the persistence and spread of antibiotic resistance.

The Biochemical Arsenal of Earthworms

A particularly critical element in the earthworm’s success is the potent biochemical activity of its mucus and coelomic fluid, which permeate the composting mass. These secretions are not merely lubricants but a dynamic chemical arsenal rich in bioactive molecules, including antimicrobial peptides, lysozymes, and DNases. These compounds launch a direct, multi-pronged assault on microbes, damaging their cell membranes and generating destructive reactive oxygen species that lead to cell death. Laboratory studies have demonstrated the sheer power of this fluid, showing it can reduce populations of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli by several orders of magnitude within hours. Crucially, the DNase enzymes present in these secretions actively seek out and degrade extracellular ARGs—fragments of resistance DNA floating freely in the environment. By eliminating over 90% of this extracellular genetic material, earthworms remove a key reservoir that other bacteria could otherwise acquire through horizontal gene transfer, effectively cleaning the waste on a molecular level.

The biochemical warfare waged by earthworms extends beyond simple destruction to a more sophisticated level of microbial control. Their secretions have been found to interfere with bacterial communication systems, known as quorum sensing, and to disrupt the very expression of genes. One study revealed that exposure to coelomic fluid altered the regulation of thousands of bacterial genes, significantly disrupting pathways related to bacterial coordination and conjugation, which is a primary mechanism for the horizontal transfer of resistance genes between different bacterial species. This interference leads to what researchers have termed an “ecological decoupling.” Sophisticated network analyses show that this process systematically weakens the statistical links between ARGs and their host bacteria, effectively disarming the resistance threat at a community level. By severing these connections, the worms ensure that even if some resistance genes remain, their ability to spread and cause harm is drastically reduced.

Optimizing and Scaling the Solution

To further enhance the efficacy of this natural system, research has focused on incorporating functional additives into the vermicomposting process. Materials such as biochar, zeolite, and various clay minerals, when mixed with the livestock manure, serve to adsorb and sequester residual antibiotics and heavy metals. These pollutants can exert selective pressure that favors the survival of resistant bacteria and can also be toxic to the earthworms and their beneficial microbial partners. By binding these contaminants, the additives alleviate this stress, creating a more favorable environment for the decontamination process. Trials have confirmed that this integrated strategy significantly boosts overall performance. It leads to increased earthworm growth and reproduction, faster degradation of organic matter, improved humification, and, most importantly, higher removal rates for both ARGs and heavy metal resistance markers. This combination of earthworm biology, mucus biochemistry, and tailored additives creates a robust, multi-level containment system that produces a safer and superior organic fertilizer.

Despite these promising results, the path to widespread, industrial-scale adoption of vermicomposting required careful navigation of several significant challenges. The variability among different earthworm species, each with unique tolerances to antibiotics and environmental conditions, necessitated precise selection for specific applications. Operational parameters, including earthworm stocking density, feedstock composition, temperature, and moisture, had to be meticulously fine-tuned to optimize performance for different types of agricultural waste. Scaling the process introduced further complexities related to climate sensitivity, efficient reactor design, automation, and the logistics of maintaining vast, healthy earthworm populations. A major unanswered question had been the long-term fate of the small percentage of ARGs that could remain in the finished vermicompost. Answering this called for multi-year field studies and comprehensive risk assessments to ensure these residual genes would not be reactivated under new environmental stresses. The way forward involved integrating advanced tools like multi-omics, artificial intelligence models for process optimization, and the development of “engineered treatment trains,” which combined vermicomposting with other technologies to achieve a complete and sustainable solution to a critical global problem.