Today we are speaking with Ivan Kairatov, a biopharma expert whose work at the intersection of public health and cancer epidemiology sheds light on one of the world’s most preventable cancers. We’ll be exploring the complex story behind cervical cancer: a disease for which we have the tools to prevent, yet which continues to cause hundreds of thousands of deaths each year. Our conversation will delve into the paradox of its declining rates but rising death toll, the stark socioeconomic divides that dictate survival, the nuances of its primary risk factors, and what predictive data can tell us about where to focus our global health efforts next.

While age-standardized death rates for cervical cancer are falling, total deaths have risen over 50% since 1990. Can you explain the key factors behind this paradox and describe a few practical, on-the-ground interventions that could help reverse the trend in absolute numbers?

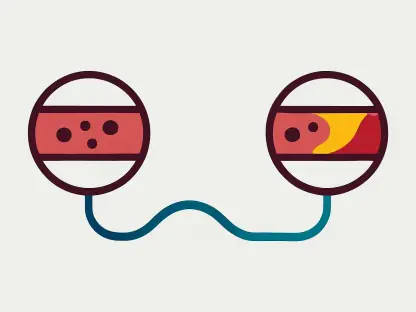

It’s a tragic paradox that highlights a fundamental challenge in global health. The decline in age-standardized rates—a drop from 8.48 to 6.5 per 100,000 people between 1990 and 2019—is genuinely good news. It shows that our preventive strategies, like screening and vaccination, are working effectively on a per-capita basis. However, the world’s population has grown significantly during that same period. This growth means there are simply more women alive today who are at risk, which has driven the absolute number of deaths up by a staggering 52%. To reverse this, we must intensify our three-pronged approach. On the ground, this means rolling out robust HPV vaccination programs for young girls to prevent infection in the first place. It also means implementing accessible, low-cost screening programs to catch precancerous lesions early. Finally, for those diagnosed, we must ensure there is a clear pathway to proper treatment and, when necessary, palliative care to improve quality of life.

Mortality from cervical cancer is 18 times higher in low- and middle-income countries. Beyond just funding, what are the most critical structural barriers to implementing effective HPV vaccination and screening programs in these regions? Please share an example of a successful, low-cost strategy.

The 18-fold mortality gap is a stark indicator of global inequality. While funding is always a factor, the most critical barriers are often structural and deeply embedded in the socioeconomic fabric of a region. We’re talking about a lack of healthcare infrastructure, a shortage of trained medical personnel, and cultural or social obstacles that prevent women from seeking care. There might not be clinics within a reasonable distance, or the cost of travel and time off work is prohibitive. A successful, low-cost strategy must therefore be decentralized and community-focused. For example, deploying mobile health units for “screen-and-treat” campaigns can be incredibly effective. Another powerful strategy is investing heavily in health education. Training local community health workers to educate women about HPV, the importance of screening, and where to access it can build trust and drive demand for these services, creating a sustainable foundation for prevention that goes beyond just building a clinic.

In low-SDI regions, the mortality risk from unsafe sex is vastly higher than from smoking. How does this disparity influence public health messaging and resource allocation for prevention? Could you outline a multi-pronged educational campaign designed to address this primary risk factor effectively?

This disparity is one of the most crucial findings for shaping public health strategy. In 2019, the data for low-SDI regions showed a mortality risk from unsafe sex of 15.05 per 100,000, while the risk from smoking was just 0.95 per 100,000. This tells us unequivocally where our primary prevention efforts must be focused. While smoking cessation is always important, it cannot be the centerpiece of our cervical cancer strategy in these areas. Instead, resources and messaging must be laser-focused on preventing high-risk HPV, the sexually transmitted virus that causes most cases. A multi-pronged educational campaign would start in schools, normalizing conversations about HPV and vaccination. It would then extend into communities through local leaders and media, using clear, non-judgmental language to explain that HPV is common and that cancer is a preventable outcome. Finally, it must integrate with clinical services, ensuring that every healthcare interaction is an opportunity to educate women about their risk and the availability of life-saving screening and vaccination.

The peak age for cervical cancer diagnosis is around 40 in developed nations but can be as late as 69 in developing countries. What does this age gap tell us about screening access and disease progression, and how should prevention strategies be tailored for these different age cohorts?

That age gap is a powerful narrative of two different worlds of healthcare. In developed countries, a peak diagnosis at age 40 reflects a system where regular screening often catches the disease or its precursors at an earlier stage. In developing nations, a peak between 55 and 69 years tells a story of delayed or non-existent screening. The cancer is often discovered only after symptoms appear, which means it has had decades to progress undetected. This demands completely different strategies. For the younger cohorts in high-SDI nations, the focus is on maintaining high HPV vaccination rates and consistent screening adherence. For the older cohorts in low-SDI countries, particularly that 55-59 age group where incidence peaks, the immediate priority is to implement catch-up screening programs. We must find these women who have never been screened and provide them with access to diagnosis and treatment, while also building a system that ensures the next generation is protected from the start.

Projections show a global decline in age-standardized rates by 2034, but absolute numbers may rise in countries like India, China, and Russia. Given that these models don’t account for future vaccination efforts, how can we best leverage these predictions to prioritize international health initiatives now?

These projections serve as both a forecast and a critical warning. The fact that the models predict a rise in absolute deaths in major population centers like India, China, and Russia—even without factoring in the potential positive impact of future interventions—should create a profound sense of urgency. We should view this data not as destiny, but as a roadmap for prevention. It tells us exactly where the global health community needs to focus its resources and partnerships over the next decade. We can leverage these predictions to make a compelling case to governments and international funders for immediate, targeted investment in these specific countries. The priority must be to rapidly scale up HPV vaccination and establish widespread, effective screening programs now. Acting decisively today could completely alter that 2034 trajectory and prevent tens of thousands of future deaths.

What is your forecast for the global fight against cervical cancer over the next decade?

My forecast is one of cautious optimism, but it hinges entirely on our commitment to equity. Over the next decade, the science will not be our primary challenge; we already have the powerful tools we need with HPV vaccination and effective screening. The real battle will be in implementation and access. I predict we will continue to see a decline in global age-standardized rates, but the true measure of our success will be whether we can finally begin to close that shocking 18-fold mortality gap between the world’s richest and poorest countries. The focus must shift from discovery to delivery. If we can mobilize the political will and resources to make prevention and treatment a reality for every woman, regardless of where she is born, we have a genuine chance to put this preventable cancer on a firm path to elimination.