The quiet confidence that comes with taking a daily pill to manage cholesterol or blood pressure often masks a dangerous misconception that its protective shield is impenetrable, regardless of what one eats. This belief, however, is being challenged by rigorous scientific inquiry, forcing a re-evaluation of where medication ends and personal responsibility begins in the fight for heart health. For the millions of adults relying on these prescriptions, understanding the true relationship between their pharmacy and their pantry is not just a matter of lifestyle preference—it is a critical component of their long-term survival.

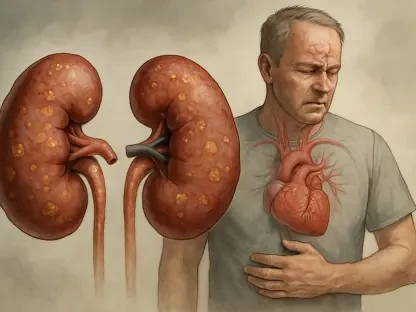

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains a formidable public health challenge, responsible for nearly a third of all deaths globally. This statistic is not just an abstract number; it translates into profound personal and societal costs, as seen in places like Canada, where 14 CVD-related deaths occur every hour. In this high-stakes environment, cardioprotective drugs have become a cornerstone of modern medicine. Yet, their rise has coincided with an unprecedented shift in global eating habits, where ultra-processed products increasingly dominate grocery carts. The central question is no longer whether these medications work, but whether their effectiveness can truly overcome the detrimental effects of a poor diet.

The Pill Paradox and Its Implications for Health

The widespread availability of effective medications for high cholesterol and hypertension has created a modern paradox. It poses a tempting question for many patients: if a daily pill is actively working to control key risk factors, does it grant a free pass to indulge in foods that were once off-limits? This line of thinking pits a seemingly simple pharmacological solution against the more demanding, lifelong commitment of maintaining a healthy diet.

This tension highlights a fundamental conflict in contemporary health management. While pharmaceutical interventions are designed to target specific biological pathways—such as blocking cholesterol production or relaxing blood vessels—lifestyle choices influence a far broader spectrum of physiological processes. A diet rich in processed foods, for instance, can promote inflammation, insulin resistance, and oxidative stress, all of which are independent risk factors for heart disease. Relying solely on medication without addressing these dietary drivers is akin to mopping up a flooded floor while leaving the faucet running.

A Modern Health Dilemma in a Processed World

The scale of the cardiovascular health crisis is staggering, establishing it as the leading cause of mortality worldwide. The relentless pace of this epidemic puts immense strain on healthcare systems and devastates families, making effective prevention strategies more crucial than ever. While medical advancements have provided powerful tools to manage risk factors like high blood pressure and cholesterol, these treatments operate within a challenging dietary landscape.

This dilemma is compounded by the modern food environment. The global diet has shifted dramatically toward ultra-processed foods—industrial formulations that are convenient and palatable but often stripped of nutrients and laden with unhealthy fats, sugars, and sodium. In response, public health authorities have implemented measures such as front-of-package nutrition symbols, designed to help consumers quickly identify products high in these problematic ingredients. These initiatives underscore a growing recognition that individual choices, guided by clear information, are a critical front in the battle against heart disease.

Unpacking the Evidence from a Landmark Study

To definitively address the medication-versus-diet question, researchers embarked on a major prospective study analyzing the health outcomes of individuals already at risk for cardiovascular events. The investigation followed more than 2,000 adults diagnosed with either hypertension or hypercholesterolemia for an average of 9.3 years. By focusing on participants who had not yet experienced a heart attack or stroke, the analysis was carefully designed to assess the role of diet in primary prevention among a medicated population.

The study’s methodology was meticulous in how it defined and measured dietary risks. Researchers categorized “foods of concern” using two distinct but complementary systems. The first was the well-established Nova system, which classifies foods based on their degree of industrial processing. The second system mirrored Health Canada’s criteria for front-of-package warning labels, flagging items high in sodium, sugars, or saturated fat. This dual approach allowed for a comprehensive evaluation of how different types of poor dietary patterns contribute to cardiovascular risk.

To determine the real-world impact of these dietary choices, researchers tracked the first occurrence of a major cardiovascular event—a heart attack, stroke, or death from cardiovascular causes—by linking the participant data to administrative health records. This objective measure ensured that the outcomes were clinically significant and accurately recorded. Using sophisticated statistical models, the analysis adjusted for a wide range of other factors, including age, physical activity, smoking status, and body mass index, to isolate the specific effect of diet.

The Verdict from the Data on Diet and Medication

The results of the analysis painted a clear and concerning picture. First, the consumption of problematic foods among this at-risk group was exceptionally high. Ultra-processed foods made up as much as 41% of the total daily diet by weight for some participants, demonstrating that even those under medical care for cardiovascular risk factors frequently rely on these products. This finding highlights a significant disconnect between medical treatment and everyday dietary behavior.

More importantly, the data established a direct and quantifiable link between diet quality and health outcomes. For every 10% reduction in the proportion of ultra-processed foods consumed, individuals experienced a 13% lower hazard of developing cardiovascular disease. A similar reduction in risk was observed when analyzing foods that would qualify for front-of-package warning labels. This dose-response relationship provides powerful evidence that even modest dietary improvements can yield substantial protective benefits.

The most crucial discovery, however, was that the benefits of a healthier diet were entirely independent of medication use. While cholesterol-lowering drugs were, as expected, associated with a lower risk of CVD, the statistical analysis confirmed there was no interaction between medication and diet. In other words, the protective effects of a good diet were not diminished for those on medication, nor did medication cancel out the harm of a poor diet. This unequivocally supports the conclusion that dietary improvement and pharmacological therapy are complementary, not interchangeable, strategies for preventing heart disease.

A Two Pillar Approach to Cardiovascular Health

This evidence solidifies the need for a comprehensive, two-pillar approach to cardiovascular wellness. The first pillar is the appropriate use of medication. Cardioprotective drugs are a vital and effective tool for managing diagnosed conditions like hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. They work on precise biological mechanisms to lower risk and are often non-negotiable for individuals with significant risk factors. However, it is essential to view them as a critical component of a larger strategy, not as a standalone cure.

The second, equally important pillar is empowerment through diet. Individuals can take active control of their health by focusing on reducing the proportion of “foods of concern” in their daily intake. Practical tools like front-of-package warning labels serve as an excellent guide in the grocery store, making it easier to identify and limit products high in saturated fat, sodium, and sugars. The goal is not perfection but a conscious and sustained shift toward whole and minimally processed foods. The most effective prevention strategy is one that integrates consistent medication adherence with deliberate and thoughtful dietary improvements.

The findings from this extensive research left little room for ambiguity. Among middle-aged adults with established risk factors for heart disease, consuming fewer ultra-processed and nutrient-poor foods was unequivocally associated with a lower risk of suffering a heart attack or stroke. This protective effect was present and powerful, regardless of whether an individual was taking medication to control their condition. This research reinforced the critical public health value of clear food labeling systems and added to the mountain of evidence against diets high in ultra-processed products. For patients and practitioners alike, the message was clear: medication is a crucial ally, but it cannot win the war against heart disease on its own. A healthy diet remains a foundational and non-negotiable element of effective cardiovascular prevention.