The long-held view of enzymes as nature’s exquisitely specific but single-minded catalysts is undergoing a profound transformation, giving way to a new paradigm that reimagines them as versatile, programmable molecular machines. This significant shift, fueled by remarkable discoveries in natural product biosynthesis and disruptive advances in protein engineering, directly challenges the classical understanding that was meticulously forged through early studies of simple metabolic pathways. We are now entering a new era of human-influenced enzymology where these biological workhorses are not just subjects of passive study but are becoming powerful, adaptable tools. This evolution in perspective unlocks unprecedented possibilities in synthetic chemistry, drug discovery, and biotechnology, heralding a future where complex molecules can be constructed with precision and efficiency previously thought unattainable outside of living cells.

Deconstructing the Classical View of Enzyme Specificity

The conventional “lock-and-key” model of enzyme function, a cornerstone of biochemistry for over a century, emerged from pioneering research on the enzymes involved in central metabolism, particularly those driving the glycolysis pathway. These proteins were ideal subjects for early investigation because they were relatively abundant, soluble, and acted upon small, structurally simple substrates, making them easy to purify and assay. This focus yielded invaluable foundational principles, including the induced-fit model, and firmly established the canonical image of an enzyme’s active site as a precisely shaped pocket, exquisitely tuned to recognize a single substrate and catalyze one specific reaction. While this work was fundamental, it inadvertently created a restrictive and lasting dogma about the inherent limits of enzymatic function, suggesting a rigidity that pervaded biochemical thought for decades, shaping how scientists approached both understanding and utilizing these catalysts.

However, this metabolism-centric viewpoint begins to fail when applied to the vast and complex world of enzymes that construct large, architecturally intricate molecules like sophisticated natural products and peptides. In these biological systems, enzymes are not merely processing simple metabolites but are engaged in a far more sophisticated task: acting as master architects that meticulously shape the entire three-dimensional structure of their substrates. Compelling evidence accumulated over the last decade, especially from studies of natural product biosynthesis, ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs), and metalloenzymes, has definitively shown that the classical rules of high specificity are often the exception rather than the rule. These discoveries have revealed that nature’s most sophisticated molecular construction machinery operates with a level of versatility and context-dependency that the traditional models simply cannot accommodate, forcing a reevaluation of the very definition of an enzyme’s role.

Nature’s Blueprint for Molecular Architecture

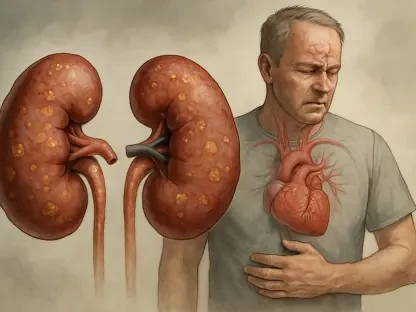

Many enzymes, particularly those integral to the synthesis of natural products, function less like simple catalysts and more like sophisticated, multi-purpose construction tools that perform a series of complex chemical transformations. The biosynthesis of RiPPs provides a powerful illustration of this principle, where a simple, genetically encoded precursor peptide is systematically and sequentially transformed by a cascade of maturation enzymes. These molecular machines perform chemistry that goes far beyond simple side-chain modifications; they are capable of forging intricate crosslinks, introducing non-standard functional groups, fundamentally rearranging the peptide backbone, and catalyzing macrocyclization to generate rigid, highly structured, and often drug-like final products. This intricate process demonstrates a programmed, assembly-line approach to molecular synthesis that is both elegant and incredibly efficient, showcasing nature’s ability to build complexity from simple starting materials.

This architectural role is further highlighted by enzymes whose functions defy simple or traditional categorization, demonstrating a remarkable degree of functional plasticity. For instance, prolyl oligopeptidases, historically known as proteases that cleave peptide bonds, are repurposed in certain natural pathways to function as highly effective macrocyclases, essential for building complex toxins like alpha-amanitin. This reveals that an enzyme’s function can be dictated by its biological context and the specific substrate it encounters, rather than being an immutable property of its active site. Similarly, asparaginyl endopeptidases (AEPs), once classified simply as proteases, are now understood to act primarily as potent transpeptidases in select plant systems, efficiently catalyzing the excision and cyclization of large peptides. These examples collectively underscore the trend that nature has evolved enzymes capable of performing synthetic feats that remain exceptionally challenging for traditional synthetic chemistry.

Repurposing Nature’s Tools for New-to-Nature Chemistry

In parallel with the discoveries illuminating the versatility of enzymes in nature, a revolution is unfolding in the field of enzyme engineering, which is actively unlocking the latent catalytic potential hidden within natural protein scaffolds. Metalloenzymes such as cytochrome P450s, which originally evolved as oxygenases designed to precisely insert oxygen atoms into C–H bonds, have become star players in this new arena. Through the application of powerful techniques like directed evolution, scientists have successfully retooled these natural proteins to catalyze a wide and growing range of “new-to-nature” chemical reactions. Engineered P450 variants can now perform complex transformations such as carbene and nitrene transfers, enabling highly enantioselective cyclopropanations and the formation of novel carbon-carbon and carbon-nitrogen bonds via C–H insertion—reactions previously confined to the domain of organometallic chemistry.

This trend is not limited to P450s; researchers are now successfully repurposing other enzyme classes, including dehydrogenases and Fe/alpha-ketoglutarate oxygenases, for non-natural transformations. Furthermore, the field is pushing boundaries by creating entirely novel artificial metalloenzymes, which are generated by embedding synthetic catalysts within carefully chosen protein scaffolds. Crucially, these biocatalysts often achieve superior selectivity and efficiency compared to the best small-molecule catalysts, all while operating under mild, environmentally friendly aqueous conditions. This pioneering work demonstrates that the distinction between an enzyme’s natural function and its potential for new chemistry is not a rigid boundary but rather a fluid concept that depends heavily on engineering, context, and a willingness to look beyond evolutionary precedent to explore the full catalytic landscape these proteins can occupy.

The Infancy of a New Enzymology

This confluence of discoveries from both natural systems and laboratory engineering culminated in a new vision of enzymology. The classical, metabolism-centric view was effectively supplanted by a broader understanding of enzymes as programmable and modular molecular machines. The evolutionary pressures that originally shaped these catalysts in nature were recognized as being largely distinct from the goals of modern synthetic biology and medicine. By shifting the guiding scientific question from “What does this enzyme do?” to “What could this enzyme do?”, researchers unlocked a vast landscape of chemical possibilities. The remarkable abilities of engineered enzymes to forge bonds beyond nature’s repertoire and of natural enzymes to construct complex molecular architectures were merely early signals of what was achievable. While nature’s enzymes were the product of billions of years of evolution, humanity’s ability to understand, redesign, and redeploy them was just beginning. From this human-centric perspective, the field of enzymology had barely emerged from its infancy, holding nearly unimaginable power to not only deepen the understanding of biology but to reshape it in profoundly useful ways.