With deep expertise in biopharmaceutical innovation and a sharp focus on oncology, Ivan Kairatov has been at the forefront of translating complex molecular discoveries into potential therapeutic strategies. Today, he joins us to discuss a groundbreaking study that shines a new light on one of cancer’s most cruel and debilitating side effects: cachexia, the severe muscle wasting that affects the vast majority of pancreatic cancer patients. This conversation will explore the intricate cellular mechanics behind this condition, delving into how researchers identified a specific pathway, IRE1α/XBP1, as a primary driver of muscle loss. We will discuss the elegant experiments that proved this connection, the immense clinical challenge of developing a targeted therapy that can distinguish between helping the patient and inadvertently protecting the tumor, and the future landscape of treating this devastating syndrome.

Your study in EMBO Molecular Medicine identifies the IRE1α/XBP1 pathway as a key contributor to muscle wasting. Could you share the story behind this discovery? What initial observations led your team to focus specifically on this pathway among many others in the endoplasmic reticulum?

It’s a fantastic question because it gets to the heart of the scientific process. We knew that in advanced cancers, the body’s systems are under immense, chronic stress. We decided to look at the cell’s “factory floor,” the endoplasmic reticulum, or ER. This is where proteins are folded and assembled. In a healthy cell, it’s an orderly process, but in the context of cancer, this factory gets overwhelmed, leading to what we call ER stress. The cell has several emergency alert systems to deal with this, and the IRE1α/XBP1 pathway is one of the most fundamental. We hypothesized that in cachexia, this alarm isn’t just ringing—it’s stuck in the ‘on’ position, sending out signals that continuously tell the muscle to break itself down. While other pathways exist, IRE1α/XBP1 is a master regulator of the cell’s response to this kind of stress, so it was the most logical and compelling suspect to investigate first.

The research states that deleting the XBP1 transcription factor “significantly attenuates” muscle deterioration. Can you walk us through the key steps of that experiment and describe the specific metrics you used to measure this improvement in muscle mass and function?

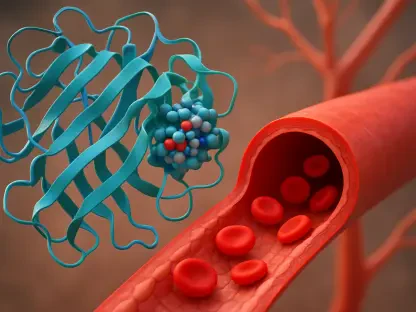

Certainly. “Significantly attenuates” is the precise, scientific way of saying we saw a truly dramatic protective effect. In the lab, we used preclinical models of pancreatic cancer that reliably develop cachexia, mirroring what happens in human patients. We then engineered a specific model where we could delete, or knock out, the XBP1 gene, but only in the skeletal muscle cells. This is a critical point; we didn’t affect XBP1 anywhere else in the body. The results were visually and functionally striking. While the control models showed the expected, severe muscle wasting, the ones without muscle XBP1 retained a remarkable amount of their muscle mass. We measured this by looking at the actual weight of the muscles and the cross-sectional area of individual muscle fibers under a microscope. Furthermore, we analyzed the biochemical markers of protein breakdown, which were substantially lower, and those for protein synthesis, which were better preserved. It was clear proof that shutting down this specific signal prevented the muscle from self-destructing.

With 60–85% of pancreatic cancer patients experiencing cachexia, this is a major clinical issue. Based on your findings, what would a therapeutic strategy targeting this pathway look like for a patient, and what are the biggest hurdles to overcome in translating this into a viable treatment?

The vision for a therapeutic strategy is a highly targeted inhibitor, likely a small molecule drug, that can selectively block the activity of the IRE1α enzyme in skeletal muscle. This would prevent the activation of XBP1 and essentially cut the wire on that ‘self-destruct’ signal. For a patient, this could mean taking a daily pill alongside their chemotherapy, with the goal of preserving their muscle mass, their strength, and their ability to tolerate the cancer treatment itself. The hurdles, however, are immense. The first is specificity. We need to ensure the drug primarily acts on the muscle tissue, which is a major drug delivery challenge. The second, and perhaps bigger, hurdle is the dual role of this pathway, which complicates everything. You can’t just carpet-bomb this pathway throughout the body without risking unintended consequences, particularly in the tumor itself.

The article mentions this pathway also influences tumor growth and resistance to chemotherapy. How does this dual role complicate the development of a therapy? Could you explain the challenge in blocking the pathway for muscle preservation without negatively impacting cancer treatment?

This is the central paradox we’re facing and the most critical challenge for clinical translation. It’s a true double-edged sword. In the muscle, the activated IRE1α/XBP1 pathway drives wasting, which is clearly detrimental. However, in the cancer cells, this same pathway can act as a survival mechanism, helping the tumor adapt to stress, including the stress induced by chemotherapy. So, if we develop a systemic drug that blocks this pathway everywhere, we run the risk of inadvertently making the tumor more resilient and resistant to treatment. We could, in a worst-case scenario, be preserving a patient’s muscle at the cost of rendering their chemotherapy less effective. The entire challenge lies in finding a therapeutic window—a way to modulate or inhibit the pathway in muscle without giving the tumor an advantage. It’s an incredibly delicate balancing act.

What is your forecast for the future of treating cancer cachexia?

My forecast is one of cautious but definite optimism. For decades, we’ve treated cachexia as an unfortunate but unstoppable consequence of cancer. This research, and other work like it, is shifting that paradigm. We are now beginning to understand the specific molecular drivers, which means we can design rational therapies. I believe the future lies not in a single magic bullet, but in a multi-pronged, personalized approach. We will likely see therapies that target pathways like IRE1α/XBP1 combined with nutritional support and exercise physiology. Crucially, I foresee a future where treating cachexia is not an afterthought but an integral part of the primary cancer treatment plan from day one, because we know that a stronger patient is better equipped to fight the tumor. The goal is to turn a debilitating syndrome into a manageable condition.